Last Monday, Nov. 30, would’ve been my father’s 99th birthday. That’s just a number, a family anniversary, and not entirely relevant since he died in 1972, cut down by a heart attack at the age of 55. And, given that he was born in 1916—on the kitchen table at his family’s modest Massachusetts home—it’s unlikely that even if his arteries weren’t clogged he’d have reached 99. Or wanted to. As it happens, my parents were married in 1940 on the same date, so that’s a mythical 75-year marker as well.

It’s a difficult reach to find silver linings in a parent’s premature death—my mother made her case to St. Peter just 11 years later in 1983—but I suppose one skips the steady decline of once-vibrant mothers and fathers, whether it’s dementia, cancer and long stays in crummy nursing homes. I’ve seen the toll it’s taken on any number of friends and relatives, and it’s just a bad situation. Sometimes a person gets lucky and is spared the indignity that most suffer in old age: for example, my sister-in-law’s father bowed out a couple of years ago at 89, but he was relatively healthy and had full mental faculties. One day he was playing tennis or golf—I forget which—had a stroke, slipped into a coma and was gone three days later. Good show, that’s the ideal way to go!

I’d just turned 17 when my father had his third, and final, heart attack (one the previous year, another in 1967 that was only discovered from scar tissue; he’d been driving home from a Brooklyn night school class one night, didn’t feel well, pulled over on the side of the road for a spell and then carried on, never mentioning it to my mother or sub-par neighborhood doctor), and while that was actuarially unusual, it didn’t certainly didn’t make me, or my four brothers, unique. Lousy, and unexpected, breaks happen all the time. But when you’re a teenager (or young adult, all of us under 30) it’s still a stab in the heart that never fully mends. I can’t count the number of wistful conversations I’ve had with my brothers over the years, thinking about dad, wondering what made him tick, and imagining him as a senior citizen.

Not surprisingly, with my father gone at 55, he became a heroic figure, frozen in time, which of course isn’t entirely accurate. I never had the opportunity to verbally spar with him, as most fathers and sons do in early adulthood, for better or worse, and then patch things up as the years pass by. My oldest brother, 29 at the time of our father’s death, and reaching a level of success in his career, had just reached a kind of equality, if that’s the right word, with dad, having conversations that wouldn’t have been possible earlier on. But I was still a kid—an independent hippie, but a kid just the same—in high school, and it was a defining event in my life (as it was for my brothers).

Before continuing, I must say this isn’t meant as a woe-is-me story, for I wouldn’t have traded those 17 years with my dad for anything. My brothers and I were fortunate in having smart, caring parents, who worked hard and selflessly to raise their five sons. Flaws and irritating tics? Plenty, of course, and my mom racked up more in my mind since I was 27 when she succumbed to brain cancer.

My father is more of a mystery: a stoic New Englander who grew up dirt-poor, an only child with a philandering, crabby father and from what I could glean, a wonderful mother (who died years before I was born). When my dad was at the University of New Hampshire, the family house burned down and his parents divorced, which was a scandal in the 1930s, especially in puritan New England. He played saxophone in a band to make extra dough, went on to become a chemist, got married and quickly started a family. After moving the family to a Levittown-style development on Long Island in the early 50s, he owned a car wash in a rough part of town that never threw off a lot of cash, although sheer perseverance led to modest monetary success. I’d have liked to chew the fat with him when I was older, digging through his past, getting him to open up about his own college capers after several drinks. I’d have liked to gotten his explanation (as opposed to my mother’s) of why his own dad was a scoundrel. The dirt!

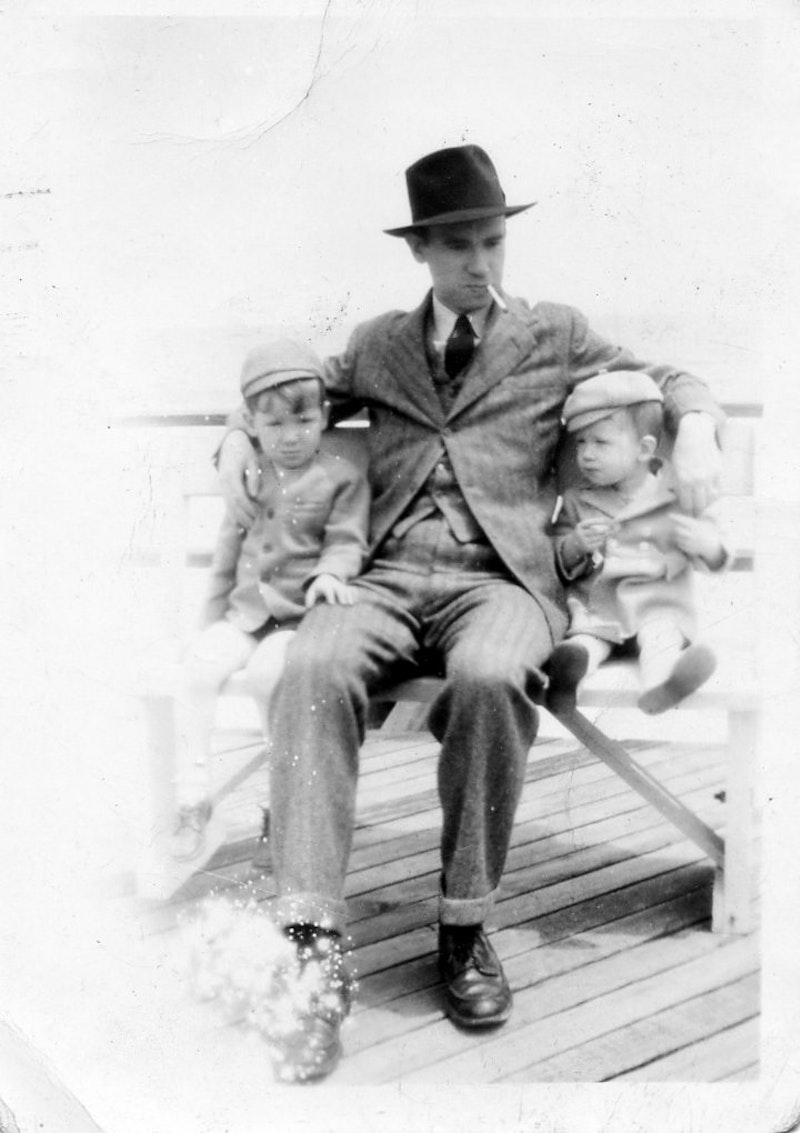

I really like the photo above, taken in 1946 at Asbury Park, dad with my two oldest brothers, sort of looking like a get-out-of-my-face gangster with the three-piece suit, scuffed shoes, hat and cigarette dangling from his mouth. That’s a romantic view obviously; for he was dressed in the attire of the day, common to almost all American men, rich or poor. One dim memory I have of dad is when he kicked the cigarette habit, several years before the ’64 Surgeon General’s report was released. The seven of us were in our Huntington house, the playroom, and he chain-smoked unfiltered Camels, puffing and puffing until he felt ill. Hard cold turkey, and he never smoked again.

One of the most memorable scenes in the film version of To Kill a Mockingbird is when Gregory Peck’s Atticus Finch, to his son Jem’s shock, picks up a shotgun and with a single bullet kills a rabid dog that’s threatening the neighborhood. No high-fives, no boasts, just taking care of business. That’s how I thought of my father—certainly not original, but true nonetheless—a compassionate, hard-working man of few words who rarely complained and was simply content to have a family life that was happier than his own growing up. Maybe that’s not the entire story, I’m sure it isn’t, but I never got the chance to find out otherwise.

—Follow Russ Smith on Twitter: @MUGGER1955