The French philosophe Michel Foucault (1926-1984) is currently up for re-assessment. In The New York Times, Ross Douthat writes that Foucault, usually thought of as a notorious postmodern neo-Marxist leftist relativist, has lately been associated with the Trumpian right. And an essay in The Point surveys the various attempts to make the French bad boy over into a neo-liberal, for heaven's sake, and condemn him on that basis. (Neo-liberalism and Trumpian populism are also completely incompatible with one another.)

Right. Michel Foucault’s not on your side. But that doesn't mean he's on the other side.

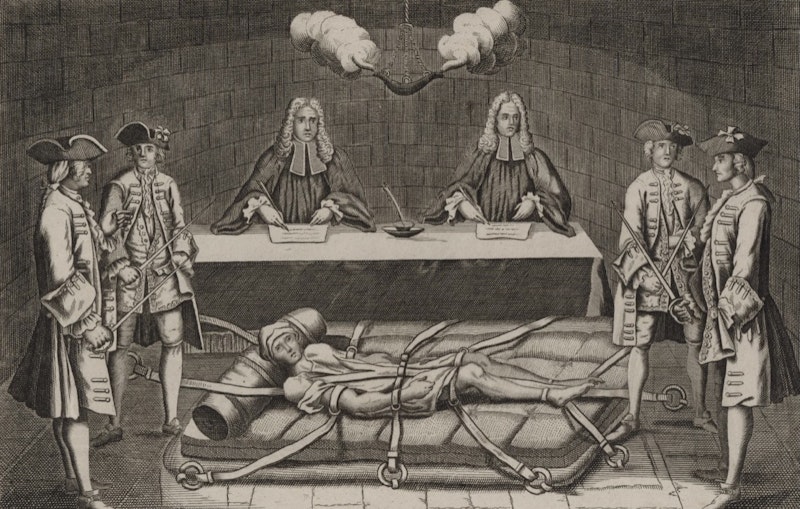

In my opinion, the most important intellectual book of the late-20th century is Foucault's Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Its argument, very quickly, goes like this. Modern systems of criminal justice and incarceration, which Foucault traces to what he calls "the classical era" around 1800, were thought of as progressive reforms to a system beset by arbitrariness and cruelty. These reforms reduced the use of torture, systematically associated specific sorts of crimes with prison terms of various lengths, and claimed, at least, to be dedicated to reforming the criminal rather than inflicting sheer punishment as a sort of collective revenge. Foucault argued that these "reforms" made the power exercised over people labeled as criminals much more pervasive and systematic (he called it "panoptic"), proceeding largely by surveillance and attempts to re-make not only the behavior of people embroiled in the system, but their very selves.

When you think you might be watched, and believe you'll undergo further punishment for misbehavior, then, as early prison reformers such as Jeremy Bentham said, you control yourself; you grow something like a conscience. But this means, argues Foucault, that you become the oppressor of yourself; it's like you have a government agent or prison guard in your head. The way that modern criminal justice re-makes selves into reflections of the power systems around them, Foucault argues, has become a model for all sorts of institutions: schools, hospitals and mental institutions, the military, taxation.

Without breaking your body, proceeding largely by surveillance with an underlying threat of coercion or punishment, these institutions are technological facilities for re-manufacturing human selves in a way useful in systems of power. They disable resistance because they install your oppressor in your very own soul. "The soul is the prison of the body," Foucault wrote in a typically bold reversal. He argued that this makes oppressive systems far more effective. If you think of such institutions as progressive, or liberatory—as their advocates did and do—you're missing what they're for and how they actually operate.

In the devastating coda, Foucault described the modern West, even with its talk of freedom, as a "carceral" society. Once you've re-manufactured people into reflections of the power systems they inhabit, once you've installed your values in their heads in your panoptic schools, you can leave them free, or give them rights. They'll just keep recapitulating the power structure, while possibly expressing their great devotion to it. "Knowledge is power," Foucault declared, and for him that’s a very dark thought.

Discipline and Punish (the French title is Surveiller et punir) was presented largely as a work of history, but it was also prescient. No one's thought sheds as great a light on phenomena such as the "surveillance capitalism" of Facebook and Amazon or the way the Chinese state rules and re-makes its people. Foucault called our society "carceral" just before what we now think of as the era of mass incarceration. But whatever his virtues as a futurist, the book—and Foucault's thought in general as also represented by his "genealogies" of the mental hospital and of sexual identities—amounted to a critique of modernity. It raised terrible suspicions about "progress."

Foucault's thought raised terrible suspicions, as well, about the social sciences, which he thought of largely as tools for surveilling, controlling, and re-engineering populations. The passage below is a good representation of Foucault's thought from Discipline and Punish. Here he uses the word “examination” to encompass legal inquiries, testing in schools, medical and psychological inspections, and gathering demographic information about populations, among other topics.

"If, after the age of 'inquisitorial' justice, we have entered the age of examinatory justice, if, in an even more general way, the method of examination has been able to spread so widely throughout society, and to give rise in part to the sciences of man, one of the great instruments of this has been the multiplicity and close overlapping of the various mechanisms of incarceration. I am not saying that the human sciences [such as psychology and sociology, also historiography] emerged from the prison. But if they have been able to produce so many profound changes, it is because they have been conveyed by a specific and new modality of power: a certain policy of the body, a certain way of rendering the group of men docile and useful. This policy required the involvement of definite relations of knowledge in relations of power; it called for a technique of overlapping subjection and objectification; it brought with it new procedures of individualization. The carceral network constituted one of the armatures of power-knowledge that has made the human sciences historically possible. Knowable man (soul, individuality, consciousness, conduct, whatever it is called) is the object-effect of this analytical investment, of this domination-observation."

Well, it's French post-structuralist theory, but it's a lot clearer than Derrida. You may quibble with this historical assertion or that, or start whining about Michel's personal life. But the basic critique, I think, is obviously true, unanswerable.

Although Foucault was influenced early on by the Marxism of his teacher Louis Althusser and was characterized at times in the 1960s as a "Maoist," the point of view articulated in Discipline and Punish is definitely not compatible with Marxism: Foucault's picture of power relations in a society doesn’t rest them exclusively on class conflicts. His critique of liberalism ended up also as a devastating critique of communist regimes, culminations of Foucault's nightmare of the carceral surveillance state. Marx's and Marxists' constant claims to be doing science must’ve merely drawn a nasty snicker.

On the other hand, Foucault would have no time for global technocratic capitalism either. In fact, he had the equipment to show that technocratic capitalism and Marxist communism aren’t as opposed as everyone seems to think. The rise of China has been a beautiful posthumous confirmation of Foucault's structure of thought.

Taking in this summary: does it put Michel Foucault on the left or on the right? Both and neither, I think, which is surely the only morally decent or intellectually plausible position. Describing Foucault as a "neo-liberal," whatever that can possibly mean, is silly. And if you think he's a reactionary, a man of the right, that just shows exactly what you mean by your leftism: the state and its surveillance, incarceration, and re-education procedures as the savior of humanity, and scientism as a sort of religion. That kind of a leftist, it's true, is a lover of everything Foucault deplored.

I read Foucault as an anarchist, that is, although he was notably reticent about connecting his thought to any definite political program, and an anarchist is just as opposed to Xi Jinping as he is to Dick Cheney and the forces of the neo-liberal front, to say nothing of Trump. In the pinhead conceptuality that pits socialism against neo-liberalism, left against right, with no other options, Foucault is just going to end up switching sides depending on the moment and who's talking. When the leftmakes a cult of science, he's there raising an eyebrow. When the right enforces borders or promises a new war on crime, he's there raising the other.

He's a consistent anti-authoritarian, and that means he's not on your side. You can punish Foucault, but you aren't going to be able to discipline him.

P.S. Michel Foucault was not a relativist.

—Follow Crispin Sartwell on Twitter: @CrispinSartwell