My father, a lifelong atheist in a family of six that my mother was determined would otherwise be devoutly Catholic, passed away last Easter Sunday. He was 94, as is she.

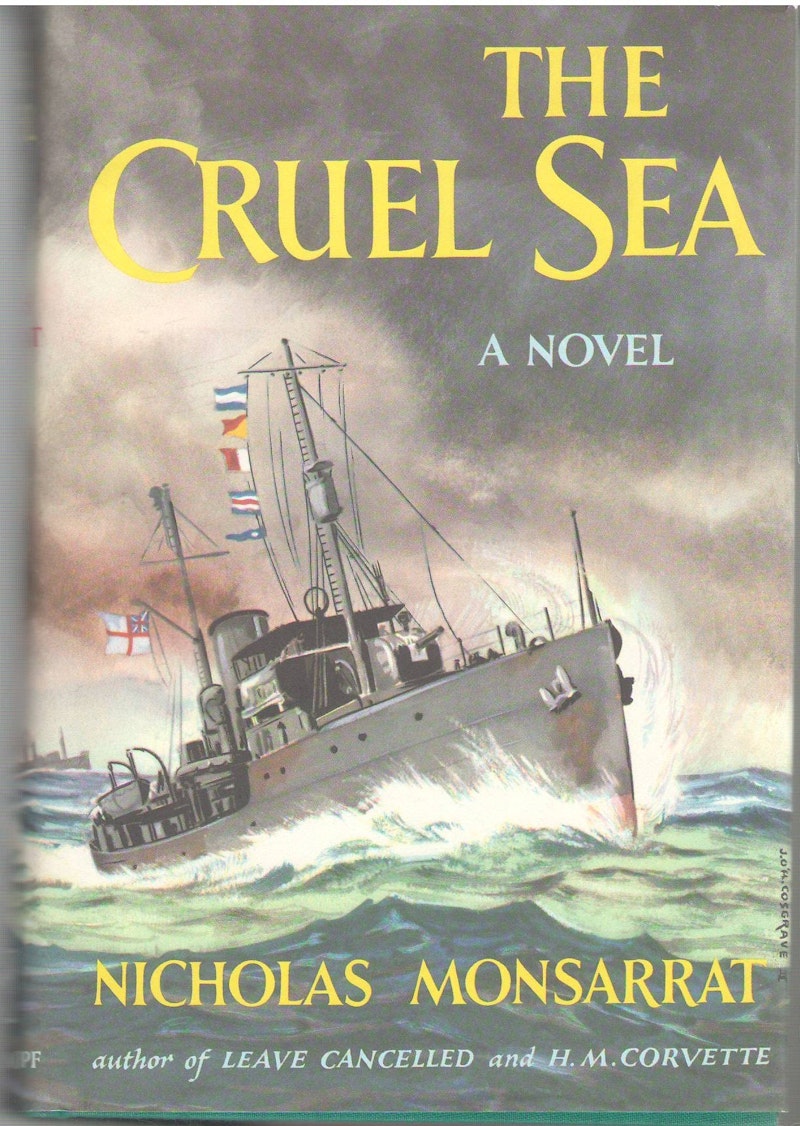

Mom has asked my three siblings and me to take books we’d like from Pop’s extensive library home with us. Perusing the shelves, I found a title that I remembered seeing on his first modest bookshelf back in the late-1950s, and wondering about it long before I could read beyond an elementary level, Nicolas Monsarrat’s The Cruel Sea.

I was looking for books with artwork, or photographs, and there were plenty of them. A favorite of mine was Gone With The Draft, by Park Kendall, which included cartoonish depictions of the life of an Army recruit. Monsarrat’s work was just a big novel, and I could only guess at the cruelties its title evoked. After reading it I knew and understood. This was a harrowing adventure on the cold Atlantic, at a time when German U-Boats stalked the merchant trade ships tasked with supplying the Allied war effort, and convoys ferried them across waters that would become the grave of thousands in the early years of WWII.

There’s a lot of history in these pages, riveting suspense, and brutal suffering and loss. There’s no larger symbolism, no subliminal premise to be divined. Only in the final pages is there a discussion among the surviving Royal Naval officers about how it all must’ve been worth it, how a failure to fight back against what in the beginning were appalling odds (convoys routinely lost a third of the ships they escorted) would’ve been to relinquish the world to tyrannical Nazism.

This is the kind of book my father loved.

An excerpt, from a scene in which Captain Ericson reflects as the balance of power has tipped toward the Allies, and his fellow officers assemble around a shipboard table:

“When the newspapers called it ‘the lifeline,’ for once the newspapers were right; and the men who had tended that lifeline for nearly four years, who had watched it being almost throttled and at last saw it easing, included, as of right, the men who now sat around the table in the wardroom of the Saltash—men who were hopeful and cynical at the same time, tired but not too tired, ready for surprises and wielding counter-surprises of their own.”

What differentiates the narrative from other celebrated war novels is the prose, which recounts horrors and interludes with the stiff-upper-lip elegance expected of a fine English writer. Monsarrat himself was a former naval officer.

The Cruel Sea—a bestseller—was published by Alfred A Knopf in 1951, the year of my birth. According to the book’s publication information, my father’s copy just missed being a first edition. It must’ve been purchased soon after he returned from his draftee service as a Corporal in the Korean War in 1952. The dust jacket is long gone, and the hardcover features Knopf’s original embossed image of Neptune. Only two years after its publication, in 1953, a film based on the book was released and become Britain’s top-grossing film of the year.

As far back as I can remember, the book has been in my father’s library along with many other rare and acclaimed books. The Cruel Sea now has a special place in mine.

—Mark Ellis is the author of A Death on the Horizon, a novel about political intrigue and cultural upheaval