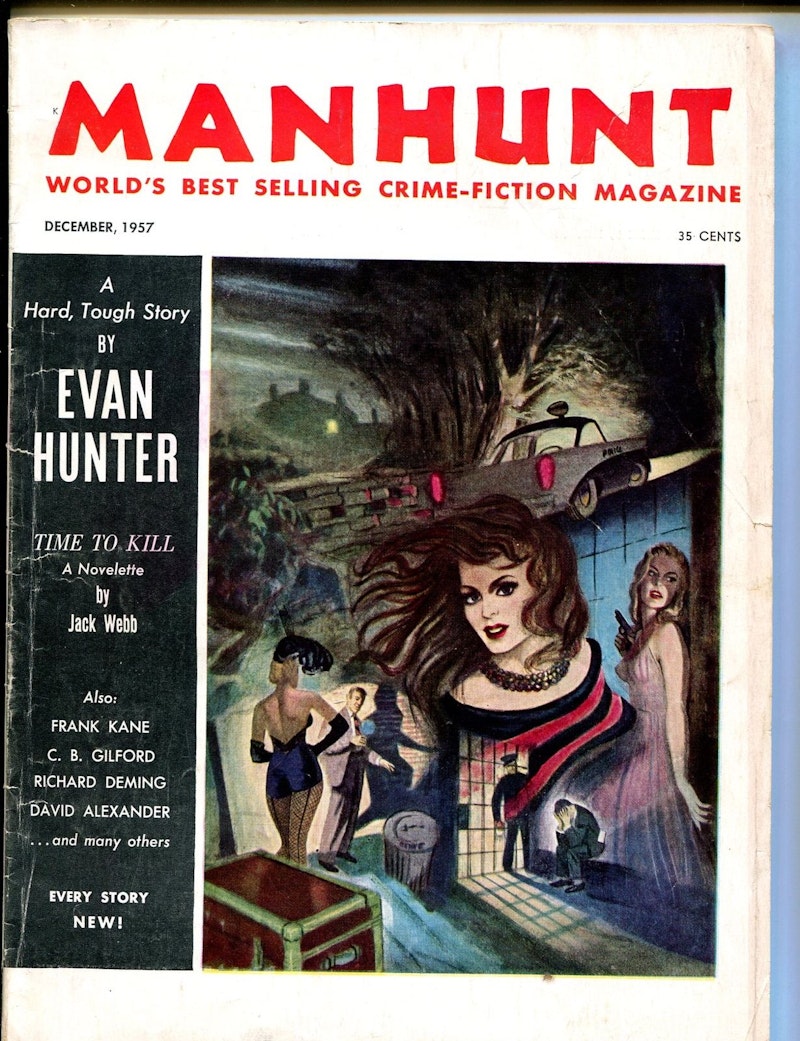

Manhunt was one of the last great pulp magazines. Dealing in hard-boiled crime and mystery fiction, it ran from 1952 to 1967, selling hundreds of thousands of copies per issue in its early years. It had a distinct editorial vision: “We don’t want the kind of story which might happen. We want the kind of story which does happen—in Harlem, on Times Square on 4 AM, on the country’s skid rows, in the isolated and struggling areas of the Deep South, places like that. We don’t want sentiment and we don’t want prettifying… We’re as much interested in the whydunit and the howdunit as the whodunit, and we want our stuff to be tough as hell…”

Now an anthology edited by Jeff Vorzimmer presents The Best of Manhunt, culling 39 stories from the hundreds published during the magazine’s run. Manhunt was born in part as a shady maneuver by literary agent Scott Meredith, working with and through publisher Archer St. John, to create a venue primarily for his writers—most prominent of whom was Mickey Spillane, represented in the anthology by the story “The Girl Behind the Hedge.” Many of the stories here strike Spillane’s kind of tough-guy pose, and pull it off at least as well as he did.

There aren’t a lot of classic mysteries in the book. There are some private eye tales, but even those are as likely to be about a guy trying to get rid of a body as about a guy trying to find a killer. Most of the stories are tight pieces about violence or its aftermath, whether from the perspective of perpetrator, victim, or witness. The prose is usually strong, terse and blunt, typically locked tight on the perspective of a single character even when not in first person. Plots are almost always sharply constructed and dramatic without simple twist endings.

The book boasts some famous names, including Spillane, Evan Hunter (aka Ed McBain), and Harlan Ellison. John D. MacDonald has one of the most powerful stories in the book, “The Killer,” a sharply-observed tale that remorselessly winches up tension. Lawrence Block (“Frozen Stiff”) and Donald E. Westlake (“An Empty Threat”) contribute the only two stories in the book from the 1960s. Which is to say the stories present a certain world of 1950s Americana.

It’s a world mainly seen from lower-class and lower-middle-class perspectives. You notice the technology of the time, how cars and phones operate, because these are stories concerned with how things get done. How to cheat people for money, how to kill them when they find out, how to dispose of their body, how the police function; so, as a result, the fiction’s shaped by how you get from point A to point B, who can get in touch with whom when, who keeps records of what, and who’s going to be able to track that information. There’s a certain kind of insularity to the stories—not only in that everything happens in the United States, but also in that the characters are isolated in a pre-Internet way which already feels distant. It’s a world struggling with corporatism and professionalization, as in David Goodis’ “Professional Man,” a story about a hit-man trying to maintain his emotional detachment from everything around him; to be the perfect systems man, setting aside love and human connection.

But if the stories build a world, they’re also about corruption within that world. About betrayal, and hatred, and lust for power, and the need for money. About the same drives to violence that have been around for at least as long as human beings.

You do notice that Georgiana Craig and Helen Nielsen are the only two women writers in the book (Nielsen contributes two stories). And you notice this because the collection’s masculine in its emphasis—male leads, often male victims. For the most part, women here are idealized love-interests, psychotic femme fatales, or secondary characters frequently in need of protection. Most of the stories are about men and their situations, men as imagined by the 1950s. I say that less as criticism and more as simple description, but it’s true that even though the stories are very strong on average if you read a lot of them at one sitting it feels as though you’re reading about the same one or two characters over and over.

Still, within their general framework, there’s a lot of variation. Fredric Brown’s allusive “The Little Lamb” is a distinctive story of an artist worried about infidelity (a constant preoccupation in the book). Evan Hunter’s two stories both follow teen gang members, but one’s a story about a youth bleeding to death alone in an alley, while the other’s a tightly-structured dialogue around a game of Russian Roulette; both are powerful.

If Hunter’s stories are two of the darker pieces in the book, none of the stories here are especially afraid to deal with darkness. Even Richard S. Prather’s relatively buoyant private-eye adventure “The Double Take” has its share of brutal moments. At their best, these are stories that aren’t afraid to explore things that more mainstream fiction of the time couldn’t articulate; stories that are knowledgeable about violence, creating strong character pieces with laconic prose. As in MacDonald’s “The Killer,” or in Gil Brewer’s “Moonshine,” which talks about a certain kind of domestic violence more understood now than in the 1950s.

Conversely, where the stories fail, it’s often because they rely on conventional ideas from their time. Robert Turner’s “Movie Night” expresses such a fear of juvenile delinquency that craft’s overwhelmed: the result is slack prose and a weakly-constructed plot. Fletcher Flora’s “The Day It Began Again” is a well-structured piece whose barely-concealed gay subtext unfortunately relies on old-fashioned ideas about homosexual misogyny. It’s worth contrasting that story with Hal Ellson’s “Pistol,” one of the few attempts to present a non-white lead character, in this case a black gang member. It’s not without issues, but Ellson was a social worker and therapist as well as a writer, and you can see that experience in at least some of his story.

There’s a kind of pulp realism throughout the anthology, a fierce mix of drama and verisimilitude. And there’s blunt writing that moves like a shot. I wish there’d been a section with bios of the contributing authors; on the evidence of this collection, many deserve to be better known. A convincing argument for the value of the magazine, The Best of Manhunt is essential reading for anyone interested in the history of crime writing, and an excellent collection of stories.