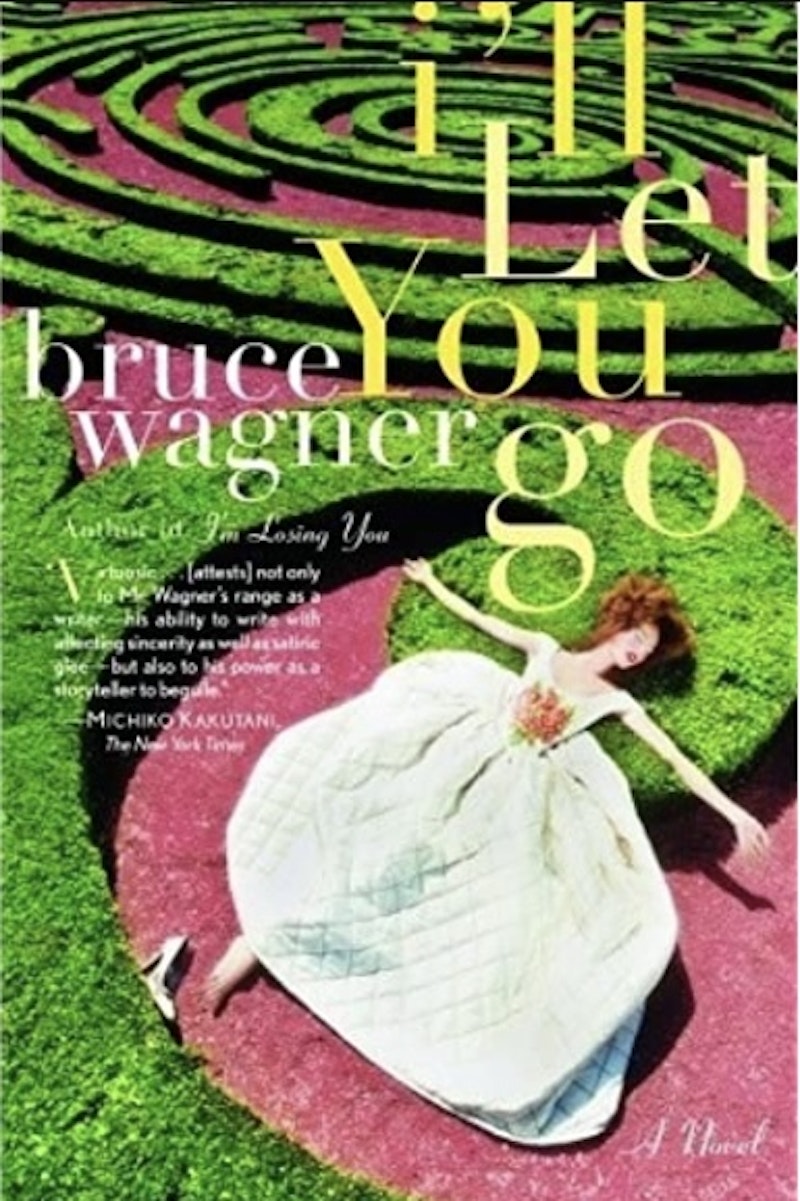

I've been reading the novels of Elmore Leonard and Bruce Wagner for years. Both hooked me right away, but lately they've competed for my attention. By that I mean that, after having completed several chapters of Leonard's Raylan (2012, a year before the author's death), I visited the local library and saw Wagner's I'll Let You Go: A Novel (2001) on the shelf. I borrowed the novel and began reading it, thus preempting Leonard, which isn't an easy thing to do.

I'll Let You Go presents a gentler version of Bruce Wagner, an author who populates his novels with repulsive characters that he has a talent for getting readers to eventually like. I recall, years ago, reading a passage from his novel Dead Stars concerning one such character whose depravity was described in such granular detail that I had to quit the book, feeling I needed a bath after reading that. Wagner loves amping up the gross-out factor, but sometimes lays it on too thick. Even though the author's aim is to skewer the shallow philistinism of contemporary, celeb-centric culture, when he goes overboard in this manner it can feel like he's contributing to the problem.

Wagner, who dropped out of Beverly Hills High School (his bar mitzvah was at the Friars Club), has the stomach to document the depths of depravity, which serves him well in his role as the top chronicler of Hollywood’s underbelly. He's often called a contemporary Nathanael West, but West wouldn't get down in the gutter like Wagner. Many of Elmore Leonard's characters are also depraved, but the author's less graphic than Wagner. In Raylan, for example, the Crowe brothers ("Coover and Dickie Crowe were still boys in their 40s. When they weren't driving around looking for poon, they hung out at Dicky's house the other side of the mountain watching porn.") are two lowlife peckerwoods from Harlan County, Kentucky who are in the business of removing both kidneys from their victims and then selling the organs back to them. Leonard spares the readers the gory details of the makeshift surgery, but Wagner would revel in detailing them, employing elegant wordsmithing worthy of Joan Didion. Leonard can't match Wagner's best sentences—almost nobody can—nor does he try. His aim is to focus the reader's full attention on his characters, with no distractions. Nobody needs a dictionary to read Leonard, but most (including myself) are going to want to have one handy for Wagner.

Wagner paints Hollywood—his town—in a scorched-earth manner. It's a moral wasteland, but he allows some of his characters room for redemption. The author showcases that town's moral malaise via sociopathic studio execs, AIDS-infected porn stars, and drug-crazed paparazzi on the prowl for celebrity crotch shots or news of celebrity illnesses to report on.

Leonard, a longtime resident of Detroit, focuses on his own town too, with frequent excursions to Florida. He's been called the "Dickens of Detroit," but I don't see it after reading at least 10 of his novels. Wagner, with his wordiness and elaborate plots, is more Dickensian, especially in his wordfest, I'll Let You Go. Leonard's the opposite of wordy. Rule number 10 in his "Ten Rules for Good Writing": "Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip." Wagner doesn’t subscribe to this rule. I skipped over many passages in I'll Let You Go before returning to Raylan.

One of my criteria to judge a film as excellent is that I never have an urge to fast forward, even upon several re-watchings. Wagner doesn’t achieve anything close to this level of leanness with this book. I skimmed passage after superfluous passage because I was, at least at first, determined to finish it.

Still, when Wagner's clicking, he'll stun you. Here's his depiction, from I Met Someone of a sex scene: "They lay in a field of golden land mines that went off one after the other, leaving them eyeless, limbless, heartless—dead and alive all at once." This is the work of a virtuoso. But there are also misfires when the author's not able to hold back. In Dead Stars, there's a reconciliation between an estranged mother and daughter: "When Reeyonna at first saw her, her features broke loose from their tenuous corral and spasmscattered, roving mountainscapes parched and dead. Mother Jacquie imperturbably rounded them up." That doesn't work because the poignancy of that moment gets overshadowed by the too-clever words. And here's a real doozy: "Embedded in the lining of the net, the Fappening’s birth had been inevitable, yet fate and history had chosen him to summon the lava flow of exposed taboo bodymaps—Jennifer Lawrence’s and lesser cousins—that verily swamped Old Reality, engulfing the pristine, elitist coastal cities of the lascivious, clay-footed gods of TMZ."

At the end of Leonard's Ten Rules, he added, "My most important rule is one that sums up the 10. If it sounds like writing, I rewrite it." From what I've read by Wagner, I'd guess he often rewrites sentences that don'tsound like writing. There's room for all kinds of approaches to fiction. Not everyone has to be a Leonard stripping their prose down to the bare bones, but Wagner tends to overwrite, and he's often under-edited.

So Leonard won this literary battle. I'm thinking I won't pick up I'll Let You Go Again, after finishing about 200 pages. One thing I found annoying about it was the endless mention of brand names I'd never heard of, and their prices. The Detroit author's spare style was influenced by Hemingway, but he doesn't take himself as seriously. There's plenty of bad guys in a Leonard novel, but he makes them fun. That's one of the secrets to his success, along with a knack for deadpan dialogue, something I'm guessing had an influence on Quentin Tarantino.

Bruce Wagner's literary superpower is his ability to introduce repellent characters and then slowly entice readers into caring about them. Whereas Leonard's market-oriented, Wagner doesn’t want his work to be accessible or friendly. He wants to challenge readers, not make them comfortable with something they're familiar with, which is Leonard's approach.