The WWE Network, for all its warts and blind spots, carries the entire Jim Crockett Promotions pay-per-view catalogue. Starrcade ‘83 was the granddaddy of those events, a closed-circuit wrestlepalooza that preceded the debut of Vince McMahon’s much glitzier and much less entertaining Wrestlemania by two years.

Since it wasn’t an event I’d watched on tape during my youth and thus felt some nostalgic yearning to see again, I didn’t expect much from Starrcade '83. I had, however, watched the Roddy Piper/Greg Valentine and Ric Flair/Harley Race matches on WWE compilation DVDs released in the mid-2000s. And those matches are indeed great—they’re perfectly paced, the crowd is into them, and the finishes are skillfully done.

But what stands out about the first Starrcade is how all of the other matches are at least fine, and many of them, like Bob Orton Jr./ Dick Slater vs. Mark Youngblood/Wahoo McDaniel, are far, far better than they needed to be. Until I moved to rural North Carolina in 1989, I’d no idea that the non-main events weren’t supposed to be five-minute, muscle-man squashes preferred by McMahon… yet here were Orton and Slater, wrestling in the middle of the card but still hurling themselves around the ring, bumping an eager Youngblood every which way but loose, and performing daring moves (top-rope superplexes, etc.) that wouldn’t be seen in WWE rings until the highspot-afflicted ECW and its cast of beer-bellied, t-shirt-wearing bump-takers forced McMahon’s hand.

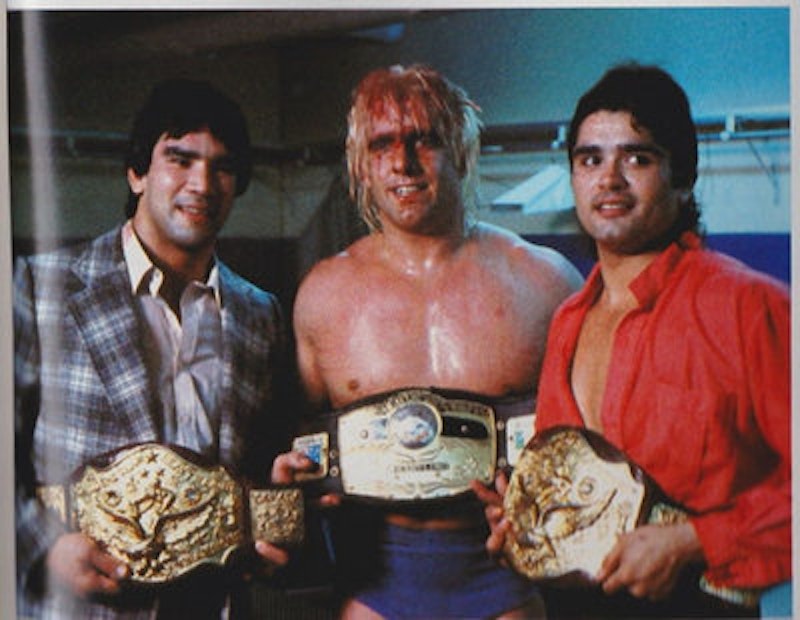

More than that, it’s all played straight—the backstage interviews with Flair and Race, Gordon Solie’s matter-of-fact commentary (even when he gets points wrong, like the fact that the Piper/Valentine match isn’t for Valentine’s US title, it’s the kind of thing a real sportscaster would stumble over), and the earnest attitudes of all involved parties. The seemingly pointless booty-shaking of Rufus R. Jones and Bugsy McGraw works in the context of an entertaining match against the villainous, all-business Assassins, and even the “we’re going to roll around while driving spikes into each other’s heads” vibe of Abdullah the Butcher’s showdown against Carlos Colon doesn’t detract from the show’s realism. Manager Gary Hart, far from flitting around the ring like a craven coward in the manner of most WWE mouthpieces of the early 1980s, takes a dropkick from Mark Youngblood and then coolly produces a foreign object from his boot, a device with which Wahoo McDaniel, Youngblood, and intervening ex-CFL star Angelo “King Kong” Mosca are all bloodied.

So it’s decidedly an autres temps, autres mœurs kind of thing—the Southern fans weren’t the sort of people who necessarily savored the sport’s clear Barthes-ian signs. No, they were used to blood, they were used to athletic spectacle, but most importantly of all, they were used to “wrasslin’.” The world we have lost, with all of its genuine regional differences, has left sports like NASCAR and professional wrestling unmoored from their foundations.

Once upon a time, Ric Flair, Wahoo McDaniel, and Dick Slater were supermen. Prior to 1990, when Ted Turner decided to take the wrestling superstars on his TBS Superstation nationwide in pitched battle against the WWE, these saggy-bodied titans stood for everything great about the distinctive sporting culture of the New South. They bestrode the performative spaces below the Mason-Dixon line like colossi.

Now wrestling is just another empty, mass-produced entertainment: it’s neither fake nor real, but is instead a billion-dollar business that means no more or no less than anything else that’s bought and sold in the attention marketplace. A well-worked WWE match goes down easy, like a Big Mac or a McRib, and leaves a similarly empty and unsatisfying aftertaste. But everything that came before this inevitable state of affairs meant something, and its end wasn’t nothing. Starrcade 1983 constitutes some of the hyper-real residue of a time that, had it not been preserved on video, seems as if it couldn’t have happened at all.