With the notable exception of the overrated movie M*A*S*H and its long-running sitcom spinoff, the Korean War has little presence in American popular culture or historical consciousness. Despite both South Korea’s increasing economic and cultural influence, and ongoing diplomatic tensions with North Korea, the Korean conflict’s still called the “forgotten war” in North America. But Michael Pembroke’s recent book Korea: Where the American Century Began makes a strong case for the importance of the war in understanding not only the present moment in the Korean peninsula, but also American foreign policy over the last 70 years.

The book argues that the war displays tendencies and themes that later emerged in Vietnam, Iraq, and elsewhere. But Pembroke also implies a possible reason America’s never seriously studied the Korean War: it’s too dark a subject, with too much guilt.

The book’s fairly brief, and covers a lot of ground. Early chapters give a background to Korean history, while the last fifth examines what’s happened to the Koreas and the United States in the years since the war. That doesn’t leave much space to cover the conflict itself, and Pembroke avoids battle-by-battle coverage of the three-year war.

That’s understandable. After small-scale skirmishes led to a North Korean invasion of the South in 1950, an American-led push northward drove almost all the way to the border of North Korea and China before the Chinese in turn launched a devastating counterattack—after which came two-and-a-half-years of stand-off on the 38th parallel. If the Korean War looks forward to Vietnam and Iraq, it also looks back to World War One in its deadlock of armies, and the high cost in lives to take a hill or little piece of land that would be lost a week or a month later.

Pembroke’s prose is good, and the organization of his material is effective. After his introduction to Korean history, he discusses the high-level geopolitics that led to the war, looking at the motivations and decisions of the United States, the Soviet Union, and China. Then in describing the war itself he looks closely at the experience of the American retreat of the late-1950s, followed by a series of chapters about the American bombing program of the North, the temptation to use nuclear weapons, and the strong evidence that America engaged in biological warfare. A section on the armistice negotiations is followed by the chapters on events since the war.

There’s a sense in which Pembroke’s Korea isn’t one mid-sized book so much as a series of shorter books. History, political study, war story, it’s all of these by turn. But it’s at its grimmest when it becomes what the French sometimes call a livre noir, a history that uncovers dark truths. Pembroke describes the massive scale and death toll of the American bombs in the North, and gives detailed descriptions of the effect of a new weapon the United States first used in Korea: napalm.

He also writes about how close both Truman and Eisenhower came to using nuclear weapons. There’s a way in which the Korean War anticipates global warming—the inability of American leadership to understand technology’s power to alter and end the world. But, having established that the War was largely led by the United States with minor contributions from a few allied countries, the overall theme of these chapters is the United States’ embrace of morally repugnant tactics. That’s important to understand, as Pembroke observes, because the scale of American bombing in the North is still felt there as a living reality. Infrastructure and civilian towns were targeted. By the end of the war, two-four million people were killed, wounded, or missing; 70 percent of those were civilians.

The bombing’s been called a war crime, and Pembroke shows that it grew out of a general attitude both to Korea and the world at large. “Then and now, the military and foreign policy establishment in Washington had a fetish for ‘credibility’ at the expense of proportionality,” he says; anyone who defied the United States would suffer the most pain the military could inflict, on the theory that this would lead to political concession. It didn’t, in Korea, and usually hasn’t since. But in Pembroke’s telling it was in Korea that the seeds of the “Green Lantern theory of geopolitics” were planted: the idea that the projection of willpower could get the United States what it wanted.

American high-handedness was visible before the war in the racism and contempt for democracy the United States displayed in its administration of South Korea, and Pembroke doesn’t shy away from discussing that, either. Originally thankful for the liberation from the Japanese and protected from the Soviets, Koreans were soon alienated by American colonial attitudes and the installation of dictator Syngman Rhee. Again, American policy preferred to set up a friendly strongman rather than trust to the democratic process.

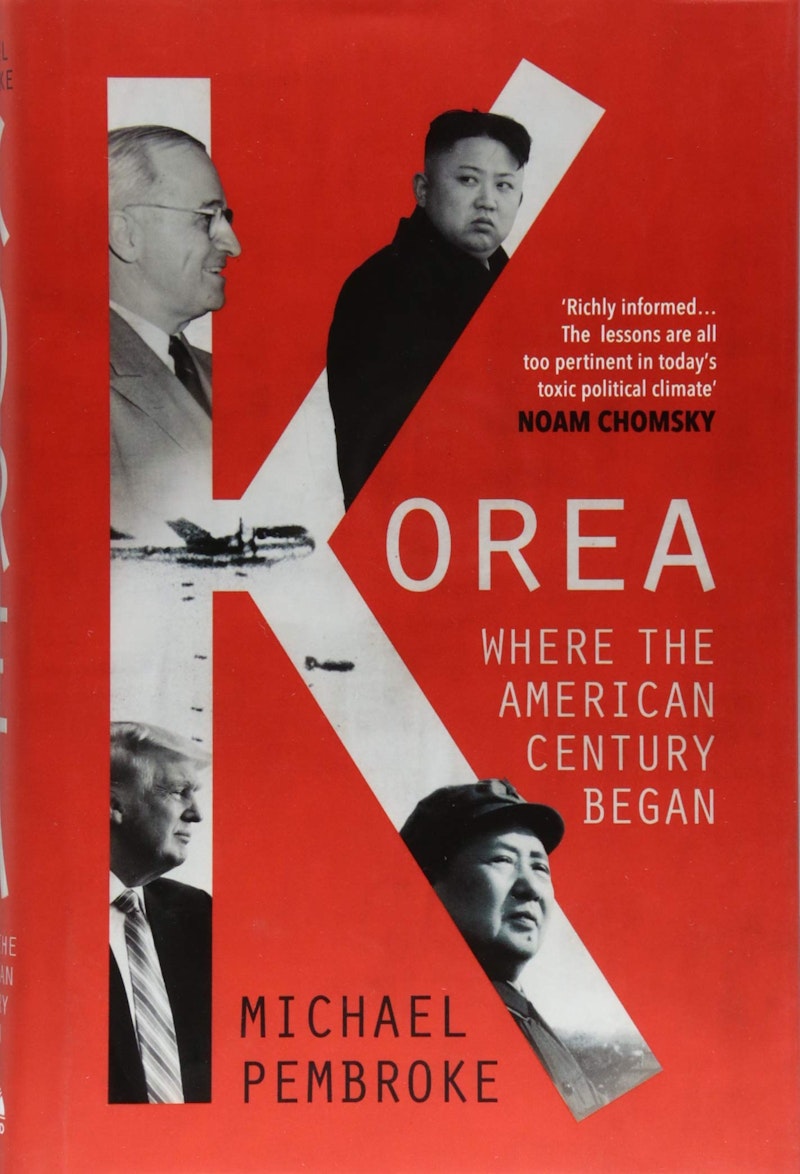

It’s not surprising that Pembroke cites Noam Chomsky in his notes - see him thank Chomsky for reading the book in proof. There’s a Chomsky-like willingness to name and criticize American imperial attitudes. But this is a book clearly born from a long-term engagement with the subject. Pembroke writes about having travelled to North Korea, and describes modern Pyogyang with first-person authenticity. He also writes about his father, who served in the Australian military in Korea; his writing has a clear personal dimension to it.

That doesn’t invalidate the scholarship. In fact, it lends power to Pembroke’s entire project. The book does two things that might’ve been contradictory. First, it establishes the importance of the Korean War as an event specific to itself, not simply a prelude to Vietnam. Second, it establishes the war as an event that displays habits, tendencies and themes in American policy that would manifest in Vietnam and Iraq. One may quibble with the sense of chronology that would call the stretch of time since the war “the American century.” But, in Pembroke’s telling, the significance of the Korean War and its lessons are clear.