The Criterion Channel has a great memory for film curiosities: movies that came and went and didn’t make much of a ripple, but which years later are worth a look. For whatever reason their “Frame of Mind” collection, focusing on films about psychiatry, is particularly full of those semi-precious cinema gems. Not least among them, Joan Tewkesbury’s 1979 drama Old Boyfriends.

The film’s sparing with its information, dropping you into a story with less hand-holding than it appears. After beginning with a car crash, a first-person voice-over tells us it’s the story of Dianne Cruise (Talia Shire), a woman revisiting her old relationships. She’s working her way back through the major romantic or sexual events of her early life. As she does, we slowly come to realize there’s more going on here than first expected.

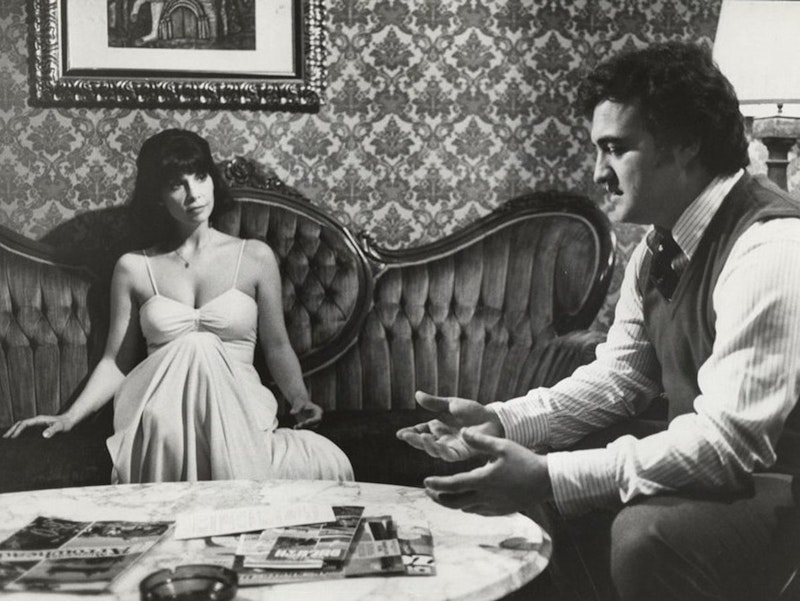

Her first stop brings her to Jeff Turin (Richard Jordan), who she nearly married in her 20s. A film director now making commercials, Turin gets curious about why she looked him up and sets off on a parallel quest, learning about Dianne’s life as she goes further back into her youth. After turning the tables on a lout who sexually assaulted her in high school (played by John Belushi with an effective sleazeball charisma), she looks up her first love, and the result is considerable damage done to an innocent person.

Not physical damage, though. It’s purely emotional, and the more effective for that. Cruise is a clinical psychologist, and the movie uses her ideas deftly, exploring issues of transference and regression. Melodrama’s largely shunned in favor of adult realism.

The script was written 10 years before the movie was made by Paul and Leonard Schrader, at which point it was called Old Girlfriends, with the genders of the characters flipped. I don’t know whether Tewkesbury, who scripted Robert Altman’s Nashville, rewrote the movie herself; there were reports at the time that the collaboration between her and Paul Schrader was, in Tewkesbury’s words, “difficult.” In any event the result is a strong though low-key character piece, if one lacking moment-to-moment dramatic tension.

After a slow start, it becomes intriguing through the second-act contrast of Dianne’s and Jeff’s journeys. Both are exploring Dianne’s past; quietly, effectively, the three dimensions of her character are sketched in. Just as things start to go wrong for her, we come to understand why she set off on her personal quest and realize just how disturbed she is.

The movie’s central theme is regression, reflected in Dianne’s character and the people she meets and even the nature of her psychiatric process (which involves having her patients play through scenarios using doll-like figures). Jeff, on the other hand, is stuck in his life; if he wants to step back to the man he was to restart a romance with Dianne, it may be the best thing for him. For Dianne it may or may not be as healthy, but she’s gone on her quest out of an awareness she needs to work through something.

It all resolves neatly enough, if with a slight anticlimax. But this isn’t a movie that lives in a tight plot. It’s a very New Hollywood sort of film, very 1970s in its interest in things that have nothing to do with its main narrative. There’s an extended sequence in which Jeff hires a private detective, for example, that does relatively little plot-wise but makes for a nice set-piece for a character who never recurs in the film. This shouldn’t work; yet it does, giving the film something of the unpredictability of real life.

Old Boyfriends isn’t the most experimental film, nor is it especially visually interesting, but there is a feel of Tewkesbury looking for new story structures, one that incorporates random asides as a way to build up the feel of life as it’s lived. The use of voice-over, say, not exactly ironic but not exactly telling the whole story. Or the way the movie builds slowly, drifting in one direction before turning in another and showing the pain Dianne’s capable of thoughtlessly inflicting.

The acting’s strong, establishing the states of the characters as they change over the course of the story. Shire tells us a story in her depiction of Dianne, in the way she makes the journey across the country a journey into her character’s psyche and past, growing more brittle until Dianne must face the consequence of her actions, and snaps. Shire’s take on the character matches the depth of the script, keeping secrets from us early on, breaking down into guilt and depression by the end.

The damage Dianne does is ably shown, and the ambiguity of the ending’s effective. The movie’s opening scenes lack in dramatic tension, but the eye for odd incidents keeps it lively. It’s a film that aims at realism, notwithstanding its quests and private eyes, and if the look is accordingly prosaic its character beats are frequently convincing.

Which in turn means that when viewed as a part of the “Frame of Mind” collection, you can see that by the end of the 1970s psychiatry’s become thoroughly everyday. There are themes in the movie borrowed from psychiatric theory, but this is fundamentally a tale of a woman stumbling around trying to construct a life in the America of 1979. There’s no genre element here, no melodrama. Psychiatry suggests some archetypes, and perhaps the form of Dianne’s journey, but if it has a part in this realist movie that’s because it has become no more or less than a part of real life.