In theory, a genre’s defined by its conventions. In practice, sometimes very weird and idiosyncratic things are given a genre tag not to describe them but to isolate them from other more respectable stories. Thus the Criterion Channel’s January selection of 1970s science fiction films included B-movie auteur Larry Cohen’s 1976 movie God Told Me To.

It’s science fiction, in terms of its plot. It’s also a horror film. And a police procedural. But mainly it’s strange, with a kind of strangeness that feels like a living reaction to the era in which it was made.

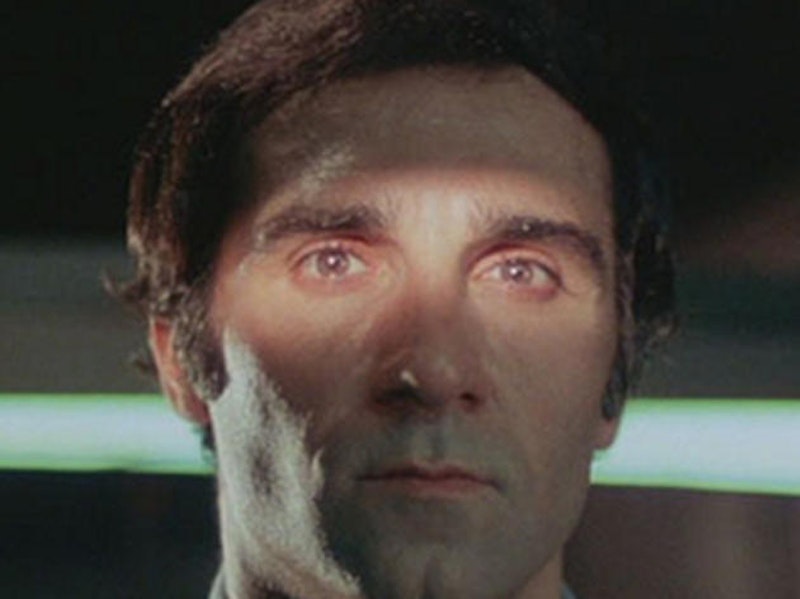

It takes place mostly in New York City, and starts when a man goes up to the top of a water tower and starts shooting random passersby. A detective, Peter Nicholas (Tony Lo Bianco), climbs up to try to talk him down. The gunman explains he shot people because “God told me to,” and jumps. Nicholas soon finds himself investigating a series of murders in which a variety of people believed God told them to kill somebody around them. Nicholas’ investigation leads him to a mysterious hippie, a financially powerful religious cult, stories of alien abduction, and finally his own early life.

Writer-director Larry Cohen started as a TV scriptwriter in the 1960s, then in the 70s moved over to directing and the world of B movies. God Told Me To isn’t self-indulgent, running a lean 91 minutes and covering a massive amount of ground. It plays like a gritty 70s police drama for a lot of that time, but as Nicholas’ investigation takes him into weirder areas it takes on a paranoiac edge. An increasingly wild science-fictional mythology gradually emerges, and it has an edge of cosmic horror.

Shooting guerilla-style let Cohen get the most out of a low budget. One notable scene has Andy Kaufman play a policeman who shoots people during the S. Patrick’s Day parade; Cohen filmed it at the actual parade, without a permit. This has the effect of anchoring the movie with a sense of place. Cohen’s eye for New York locations is strong, and there’s a patina of grit that emphasizes the lived-in utilitarian city.

If someone in 2020 tried to make a film look as much like a 1976 cop film, they’d be unable to match this movie—which isn’t something you can say about every other cop film from 1976. It’s not just a question of fashions and hair and film stock; it has to do with the way Cohen made this movie, shooting in real places and using real people in backgrounds. To use a metaphor from 1970s technology, the genre elements are like a transparency projected over the actuality of his locations. As wild as the ideas of the movie get, the feel of a cop movie set in New York at a specific time keeps it oddly coherent.

An almost obsessive fascination with violence and religion mixes with a plot driven by aliens and secret societies. Those genre elements make the film more coherent, bringing its main themes together. Nicholas, a Catholic cop investigating murders whose main suspect may be God, is able to get somewhere by investigating earthly powers which lead to an extraterrestrial but concrete culprit. At the same time, the aliens aren’t easily distinguishable from the divine, meaning the film’s subverting the idea of a truth behind religion even while trying to criticize it.

The movie doesn’t always hang together thematically, but the mix of ingredients is never ponderous due to the movie’s feverish intensity. That’s grounded in a tension between the big ideas and a hyper-focused sense of time and place. Beyond the look, the movie plays with fears and obsessions of its time. The opening scene, with a shooter on a water tower, recalls the 1966 killings at the University of Texas in which Charles Whitman shot random passersby from a high tower. The secret society of cultists recalls (but is more impressive than) the Satanists of Rosemary’s Baby: it’s the way the 1970s imagined conspiracies.

On top of that, Nicholas ends up hunting down a mysterious hippie connected to each of the killers, a kind of equivocal image of the counterculture. The hippie’s involved with murder, but that might be because he’s a messenger from God. The alternative spirituality that ranged from New Age beliefs to the Manson murders finds an ambiguous symbol here, a deity more tangible and bloodier than the Abrahamic faiths.

Nicholas is a blank slate. We learn about his background, and about his home life, and it all pays off dramatically at the climax. But for much of the movie it’s hard to get a sense of what he’s thinking. His Catholicism obviously works with the theme of the movie. And yet it’s underplayed. There’s a sense of something absent to his character. Perhaps it’s simply that God Told Me To isn’t much of a mystery; Nicholas investigates the murders, finds a lead, follows the lead to the next lead, and thus onward.

The climax is a good payoff, a resolution to Nicholas’s investigation that doesn’t cheat on either explanations or horror while also tying in with what we’ve learned about the detective. It’s a clear vindication of what’s earthly in Nicholas against the self-proclaimed divine. One may wonder whether it makes philosophical sense: if you imagine a divinity without infinite wisdom, aren’t you setting up a straw god? And yet it makes dramatic sense. God Told Me To never loses its sense of momentum, and develops an undercurrent of a specific kind of weirdness that emerges into full flower right at the end—a weirdness native to 1976.