In Brooklyn, Grand Army Plaza is where several important roads meet and is the northern end of Prospect Park. Flatbush Ave. runs southeast through the park to Rockaway Inlet; Eastern Parkway fans out east, getting as far as Bushwick; Vanderbilt Ave. runs north to Clinton Hill, and Prospect Park West stands in place of 9th Ave. as it borders the park and brings traffic as well as a controversial bike lane to Green-Wood Cemetery and Windsor Terrace.

Prospect Park’s engineers, Frederick Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, recognized this as an important crossroads and several memorials to the soldiers and their commanders who had recently fought and won the Civil War were built here. Residential architecture from the 19th through 21st centuries is found along Plaza St., which rims GAP’s border. The magnificent home branch of the Brooklyn Public Library, originally planned in the 1920s but actually built after World War II ended, and the Brooklyn Museum on Eastern Parkway mark its southeast quadrant.

Surrounding Grand Army Plaza are statues of historical and mythical men well-known in their time. For example, tucked away on Plaza St. East and St. Johns Pl., across the street from a Richard Meier glass cube building that looks like nothing else at Grand Army Plaza, is a big boulder with a bas relief of Henry W. Maxwell (shown above). Inscribed below his likeness is: “This memorial erected by his friends is their tribute to his devotion to public education and charity in the City of Brooklyn” and is signed “A ST G”—Irish-born Augustus Saint Gaudens, one of the more prolific and famed sculptors of the 19th century: the Peter Cooper statue at Cooper Square, the William Tecumseh Sherman statue at Manhattan’s Grand Army Plaza, and the Robert Gould Shaw Memorial at Boston Common and many, many others. Maxwell (1850-1902) was a banker, philanthropist and supporter of public education; he was Brooklyn’s Park Commissioner in 1884. The monument was dedicated in 1903 by Maxwell’s niece at what was then the Mt. Prospect Library at Eastern Parkway and Flatbush Ave., now the Brooklyn Central Library. It was moved to this location in 1912 and stayed there until the 1970s, when repeated vandalism caused the Parks Department to put it in storage. It was restored and put back in 1997.

General Henry Warner Slocum can be found a little south of Maxwell at Plaza St. East just before it reaches Eastern Parkway. Slocum (1827-1894) was a lawyer and politician in upstate Onondaga County before entering battle in the War Between the States, eventually attaining the rank of general. He fought at Bull Run, Georgia, the Carolinas and Gettysburg, where his leadership was not without controversy. In 1866 he moved to Brooklyn and was twice elected a US Representative, in 1868 and 1870. Unfortunately, Slocum’s name is most recognizable as the steam excursion vessel that caught fire in the East River in June 1904, killing over a thousand German immigrants in the greatest NYC death toll in one day before the events of 9/11.

Sculptor Frederick MacMonnies is well-represented in NYC by Slocum, the Quadriga and Army and Navy base reliefs on the Grand Army Plaza arch, James Stranahan, the “father of Central Park” (see below), Nathan Hale in City Hall Park, and the controversial Civic Virtue, depicting a heroic figure lording it over a pair of sea sirens (depicting Vice) now in Green-Wood Cemetery after several decades near Queens Borough Hall.

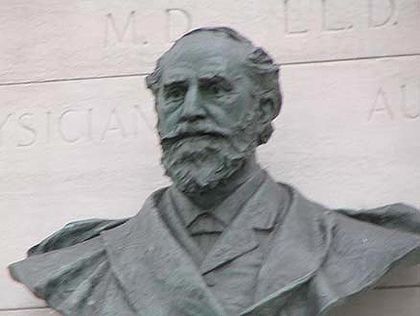

Located at Plaza Street East and Flatbush Ave. is the only bust in NYC of a gynecologist, Alexander Skene (1838-1900). (There had been a statue on the Central Park side of 5th Ave. of James Marion Sims, a second gynecologist; it was removed when his dubious experimental practices were brought to light). Born in Aberdeen, Scotland, Skene worked in Toronto and Michigan and served in the Civil War as a surgeon in South Carolina and New York, settling in Brooklyn after the war. He became an adjunct professor at Long Island College Hospital in 1865 and rose to president of the school, serving from 1893-1899. He was founder of the American Gynecological Society in 1866. He discovered the pair of para-urethral glands that are today called the Skene glands.

After his death Scottish sculptor John Massey Rhind created this heroic bust. Skene was an amateur sculptor himself, creating a bust of Sims that today is located in the Kings County Medical Society.

Sculptors operating in the 19th century and early-20th had an enthusiasm for portraying scenes from classical myth; there were many opportunities to show sea scenes, and the denizens therein—think of the unnamed terra cotta artists who created the Coney Island Child’s Restaurant, or the Lillian Goldman Fountain of Life at the NY Botanical Gardens in the Bronx. Probably NYC’s finest example in the genre is the Bailey Fountain, in the pedestrian plaza directly in front of the Grand Army Plaza Arch.

The Bailey Fountain, named for Frank and Marie Louise Bailey, who made extensive donations ($125,000, in the millions in 2010 money) for a new fountain in Grand Army Plaza that would replace two previous ones on the site, is a relatively new piece of classical sculpture—it was completed in 1932. It took $2 million to restore the fountain in 2002.

Neptune, the Roman sea god, is only part of the proceedings here, as there are two male and female figures standing on a ship’s prow, symbolizing Wisdom and Happiness. The fountain is spectacular in season when it’s turned on and is surrounded by water jets. “Wisdom and Happiness” is accompanied by an unnamed child as well as a pair of conch blowing mermen. Fishes and frogs are scattered about the ship. The fountain is an engaging sight when its water jets are turned on.

A depiction of General Gouverneur Kemble Warren (1830-1882) can be found at Flatbush Ave. and Union St. A surveyor and engineer by trade, he arranged a last minute defense at Little Round Top at the Battle of Gettysburg; while he was regarded as an architect of the Northern victory there, he was less successful at the Battle of Five Forks in Virginia and was relieved by General Philip Sheridan.

Warren was born in Cold Spring, NY. He remained in the Army after the war, working in surveying and harbor improvements. Another statue of Warren was erected at Round Top at Gettysburg, on the sixth anniversary of his death. Rendered here, in an elegant standing portrait by Henry Baerer, Warren’s pedestal includes a slab taken from the very outcrop on which he won the Battle of Round Top.

Prospect Park is, in good part, the brainchild of railroad builder James Stranahan (1808-1898), who headed a board of commissioners selected by New York State in 1859 to investigate areas to build a public park in Brooklyn similar to the one then under construction in Manhattan. Seven proposals were offered, including Ridgewood and Bay Ridge, which weren’t then in the city of Brooklyn proper. Another was on a hill called Mount Prospect, on the road that would become Flatbush Ave. near the Brooklyn-Flatbush town border. This location was selected, and the commissioners tapped Egbert Viele, who was chief engineer of Central Park, to begin work on the project.

But Viele’s designs were torpedoed by the outbreak of the Civil War. At the conclusion of hostilities, the plan was placed in the more than capable hands of Frederick Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, who’ landscaped Central Park before the war. Prospect Park was completed by 1870. (Viele’s consolation prize is that his 1865 map of Manhattan’s underground waterways is still in use today by architects and engineers.)

The statue, by Frederick MacMonnies (see above) was dedicated June 6, 1891; Stranahan was present.

One of the first monuments to President John F. Kennedy appeared in 1965 at the north end of Grand Army Plaza. It replaced a large statue of Abraham Lincoln, which was then relocated deep in the park in the Music Grove, near the old Wollman Rink. The bust, sculpted by Neil Estern, was originally poorly fitted on its pedestal and then subject to vandalism. After several years’ absence, it was restored and replaced in August 2010.

—Kevin Walsh is the webmaster of the award-winning website Forgotten NY, and the author of the books Forgotten New York (HarperCollins, 2006) and also, with the Greater Astoria Historical Society, Forgotten Queens (Arcadia, 2013)