“I was still playing chess with Moses and plenty of sports,” Woody Allen tells us of Mia Farrow’s adopted son. “He had asked me to be his father, and I thought he was a great kid and agreed. I didn’t legally adopt him at that point, but as he’ll tell you, I was his father in every substantial way.” That’s from Allen’s recently published Apropos of Nothing, a book as chronologically vague as most showbiz memoirs. Going by what’s there, Moses was perhaps seven years old, maybe a little older or younger. Soon-Yi had been his big sister for at least five years. Eventually, as we all know from history, Allen put the moves on Soon-Yi. By that point she’d been the boy’s older sister for a decade, and Allen had been his father “for years” (Allen’s phrase). In short, Woody Allen decided to fuck his son’s sister.

She was also, of course, Mia Farrow’s adopted daughter, and Mia was Woody’s girlfriend. The girlfriend found out. Soon-Yi and Woody set up housekeeping together, and Woody tried to get custody of Moses. The boy’s sister was set to become… his mother? One might ponder the effects of this on a 14-year-old, or anybody. One might, but Woody doesn’t. His book says nothing about that angle. It’s been 28 years and the thought never crossed his mind.

Allen didn’t get custody, so Moses was spared a sister-mother. Instead he had to deal with Mia. Possibly as a result, the grown-up Moses has little to say about his dad’s unorthodox parenting choice and plenty to say about Mia Farrow and life in Mia’s alleged hell-house. Apropos of Nothing cites him often. Moses, amplified by Woody, alleges abuse and humiliation by Mia; Mia and Dylan, one of her daughters, allege child molestation by Allen. Through the smoke, a lone undisputed fact: Allen wanted to put a sister-mother in his son’s life. Allen all but confesses it. I say “all but” because he’s too indifferent to connect the dots. He tells us he was the boy’s father, he tells us he took the boy’s sister to wife. Then he sees nothing to add except that Mia Farrow’s crazy. Moses seems indifferent too. All he does is trot out the talking points about Soon-Yi not being underage, not being mentally defective, not being Woody’s daughter. No, but she was Woody’s son’s sister—that is, bub, your sister. This doesn’t get a look in. It’s all very strange.

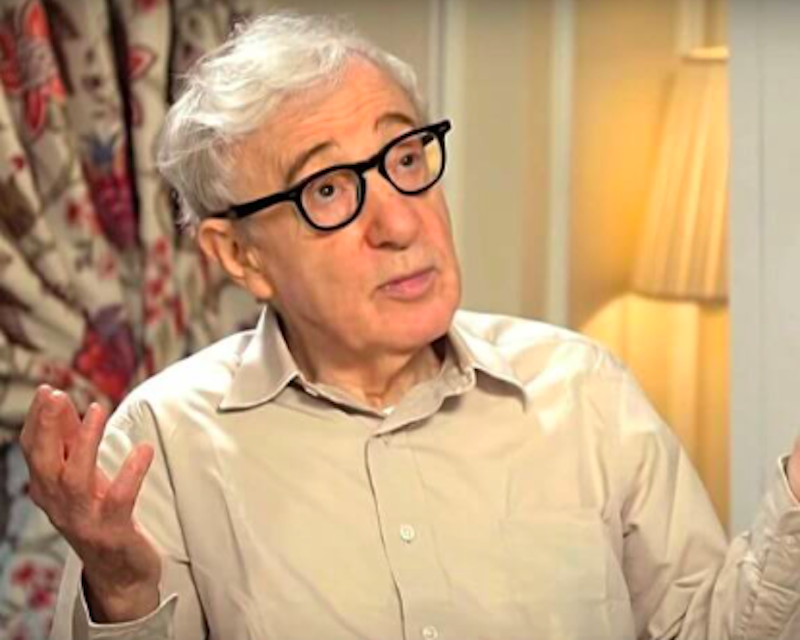

Another puzzle: Allen’s book is charming. I called Apropos of Nothing a showbiz memoir. I should’ve said a chatty showbiz memoir. Allen rattles along and you can see how so many intelligent, high-powered people enjoyed his company. He’s a very smart, alert man with a verbal gift and a ton of energy. When young he managed essays that were decent imitations of S. J. Perelman, a writer whose baroque curveball prose causes wannabes to pratfall. A skim milk version of that style carries Apropos as it trots through the years of Allen’s life. On the time the young Allen sassed his dad: “He made his displeasure known with a gentle tap across my face that gave me an unimpeded view of the aurora borealis.” Incidentally, Allen says his mother hit him every single day he was a child, “at least once.” I mention this because of what he says about Mia Farrow’s crazy family background and how it throws doubt on her stability.

Joke, anecdote, celebrity name, opinion, joke, joke. A young reviewer for The Forward broke into tears while reading Apropos. Allen had just described his crazy first wife and how they fucked in an alley. Joke, celebrity name, anecdote, anecdote. Allen recalls Mariel Hemingway, who said he hit on her when she was 18. (She also said, though Allen leaves this out, that after their first kissing scene she demanded, “I don’t have to do that again, do I?”) Allen tells us how, decades later, he cast her in a second film: “Mariel Hemingway came by my cutting room and told me she wanted to get back into acting; she had become single and the high point of her life had been the movie Manhattan. I didn’t have anything comparable for her at the moment, but there was a part still uncast if she didn’t mind a small role.” He notes that she didn’t.

Still, Mariel did her “usual excellent job,” he says. The book’s full of language like that. Alan Alda’s a “wonderfully gifted actor.” Alec Baldwin’s “amazing… really quite a phenomenon when you think about it.” A showbiz vet like Ed McMahon, coming back from judging a beauty contest, would tell the Tonight Show audience that the population of Mobile, Alabama, was great (“There’s great hospitality down there, they’re great people”). Allen says his son, Moses, is great. In fact that’s why he’s his father (“He had asked me to be his father, and I thought he was a great kid and agreed”). The flatness here is a variant of the flatness that makes so many Allen films so dreadful. There someone missing some wrinkles on his brain tries to simulate profundity and feeling. Here this same person rattles along making no such pretense. When it came time to write of himself, Woody didn’t decide to do a Montaigne or Rousseau, the way he’s done Bergmans and Fellinis. He did a Bob Hope (Bob Hope’s Own Story) and Oscar Levant (Memoirs of an Amnesiac), and the results are more bearable. Except when some full human response on the part of the narrator/protagonist is called for—then you bite on the tin foil. It’s a great book, in the McMahon-Allen sense of the word, but it leaves a taste in your mouth.