Charlton Comics’ horror hosts were a creepy rogues gallery who smirked their way through narration with mischievous glee. A hooded elder (often rendered with decrepit glory by artist Sanho Kim) served as narrator in the first series of Charlton’s Ghost Manor that was published from 1968 to 1971. With Ghost Manor vol. 1’s 13th issue, this ragged weirdo was replaced by the sultry blue-skinned, occultist Winnie The Witch, a co-creation of writer Joe Gill and artist Steve Ditko. After 19 issues the first Ghost Manor series changed its name to Ghostly Haunts. From then on to its 58th and final issue the title became one of Charlton’s most popular horror comics thanks to Winnie The Witch’s eclectic presence. Enrique Nieto, Fred Himes, Joe Staton, Pat Boyette, Wayne Howard, and Ditko were just a few of the artists who made this character a complex icon of supernatural psychedelia.

Winnie wore big yellow mod shades and gaudy revealing ensembles in distinctly un-scary color schemes (Christmas red and green, or muted purple and white). She was a blatantly weird marriage of sex appeal and distorted emotion. Her narration was peppered with flirtatious comments and hippie lingo directed at the teenage and young adult readers of the 1970s who were probably the only people that understood the cultural significance of a sexually confident young sorceress.

Despite representing the beauty standards of her time, Winnie The Witch was no sexist stereotype. She wasn’t a nurturing mother figure dedicated to protecting humans from ghostly terrors, nor was she treated as mindless eye candy, and only once was the mod witch overcome by jealousy in confrontation with another groovy occult femme (in “Miss Fortune,” a humorous Wayne Howard short from Ghostly Haunts 42 that co-starred fellow Charlton horror hostess Arachne Coffin; the story made fun of beauty pageant culture). Winnie was always levitating around the panels of each page. Between animated moves and ominous exposition she’d glare at whatever action took place, but rarely interacted with her stories’ characters. This was the key to her power, a direct reference to her simultaneous existence outside and within the limitations of the physical world and the conventional time-space continuum.

Winnie’s crafty omnipresence exploded in some of Ghostly Haunts’ best stories, including a pair of frantic acid nightmares from the unstoppable duo of Gill/Ditko: “Kiss Of The Serpent” from GH 45 and “Return Visit” from GH 23. Both flaunt ancient themes that highlight femininity's connection to the supernatural power of snakes. Excitement builds with each page as we see the witch contorting herself as a combination acrobat/aerialist/super model/triathlete. Each story concludes with Winnie invisibly crashing the final moments of a doomed male’s fate. “Return Visit” in particular features what may be Winnie’s most seminal moment, a chilling splash page that finds her standing tall and proud, wind-whipped, clutching her purple cape while a ghostly femme fatale and a mob of possessed serpents transform two homicidal bruisers into a spineless pile of fear.

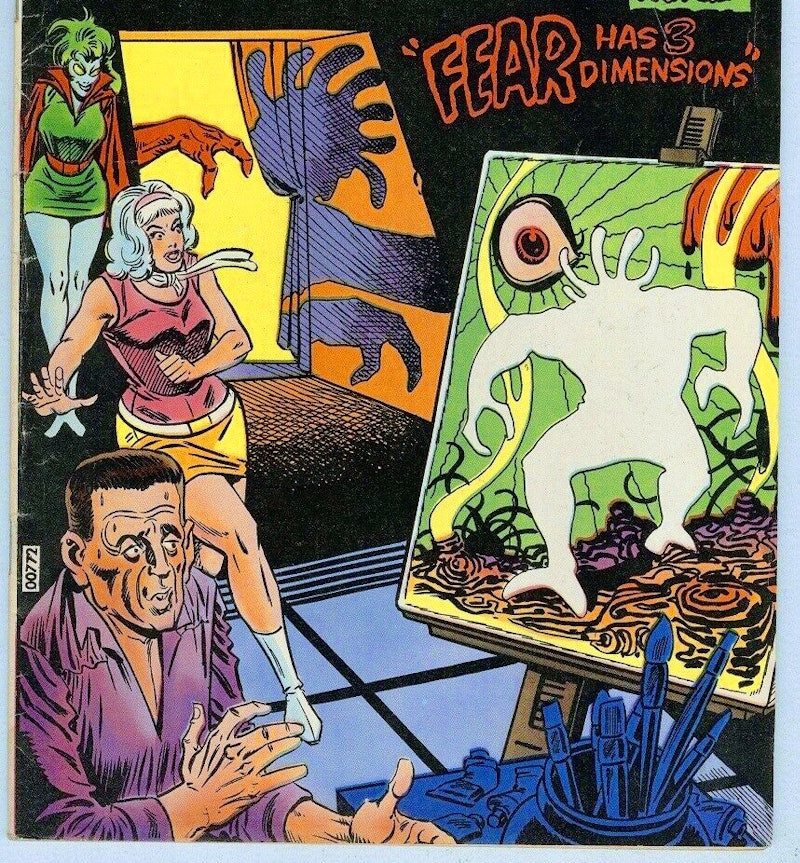

Steve Ditko was the illustrator who best captured the witch’s energy. In his hands she became a passionate orator-cum-avant garde performance artist. The cover art from Ghostly Haunts 30 features another major Ditko piece. Sporting a green rat’s nest hairdo a la 1960s Pink Floyd svengali Syd Barrett, the witch lurks in a dark corner as two mortals gaze in terror at a freshly painted canvas. It depicts a craterous hellscape surrounding a giant monster’s glowing white silhouette. Creeping up next to Winnie we see the stray art-beast’s menacing shadow and a big red claw. The witch smiles wide, striking a steadfast yet cheerful pose. She’s in awe. Her love for human fear beams and why shouldn’t it? As the mystical spinner of terrifying tales, this is what gives her lust for life (though perhaps the term “life” is not such a good fit when referring to an entity who can become visible and invisible, non-existent and existent all at once).

Though there are many tales that find her observing a quiet reverence for mayhem, that was never Winnie’s dominant trait. “The Walking Snowman”—a collaboration between Ditko and writer Nicola Cuti from Ghostly Haunts 54—was one of her final appearances. The last page of this story shows the witch standing out in the middle of a dark wintery landscape. Winnie annihilates the solemn mood of an icy death scene by gleefully hurling a snowball straight at the reader. GH 54 came out in September 1977, a point when the mainstream entertainment industry and its audiences were also responding to fatal dehumanization. Popular films, TV shows, books, and comics had become progressively more grim and sadistic beginning in the early-1960s on into the disco era. Celebrations of the ghastly were no longer an esoteric past time for Winnie The Witch or any other imaginary occultist. By late ‘77 that snowball, frozen in mid-air on a comic book page, had come to represent the stark disconnection shared by pseudo-sadistic voyeurism and the horror of death.