I was recently tasked with developing a short presentation at the Greater Astoria Historical Society at 35-20 Broadway in LIC, and I happened to have several photographs left over that were unused when I and GAHS were putting together the Arcadia book, Forgotten Queens, that was released in 2013.

As Calvin’s father said in one of the Calvin & Hobbes strips back in the 1980s, the world turned color in 1966, and that happened to be the year our family got our first Zenith color TV. Color TV wasn’t an exact science in that era and so the old man had to twiddle the knobs with some regularity as channels were changed so Captain Kangaroo or Jeannie the genie didn’t look green. But we were ecstatic to have a color set. It was my first TV when I moved out to my own place, but I had to get rid of it when the picture started sizzling and snapping, and I decided to trade going without a color TV for a while rather than start an electrical fire.

I bring all that up because sometimes, when you look over photographs from previous eras, they’re almost exclusively black and white; the means for color photography had existed from just a couple of decades after photography’s original development in the 1840s, but the process was pretty expensive until after World War II, and NBC was still making a big deal about color broadcasts until about 1970.

It’s tempting to look at old black and white photography as static, as if the scenes depicted are mere paintings and aren’t real. In fact, if you jumped in an H. G. Wells time machine and set the controls for 1940 or earlier and inserted yourself into these scenes, you may feel more alive then than you do now, as there are fewer distractions like ringing telephones, blaring TV screens, and the overwhelming background noise that’s part of living in a metropolitan area.

We don’t have that technology and likely never will. Hence, photography will have to make do as our de fact time machines now, and in the days to come. (As Johnny Rotten once said, there is no future, and he was never more on point; the future doesn’t exist, as events happening today set it in motion and there’s no future out there for us to travel to.)

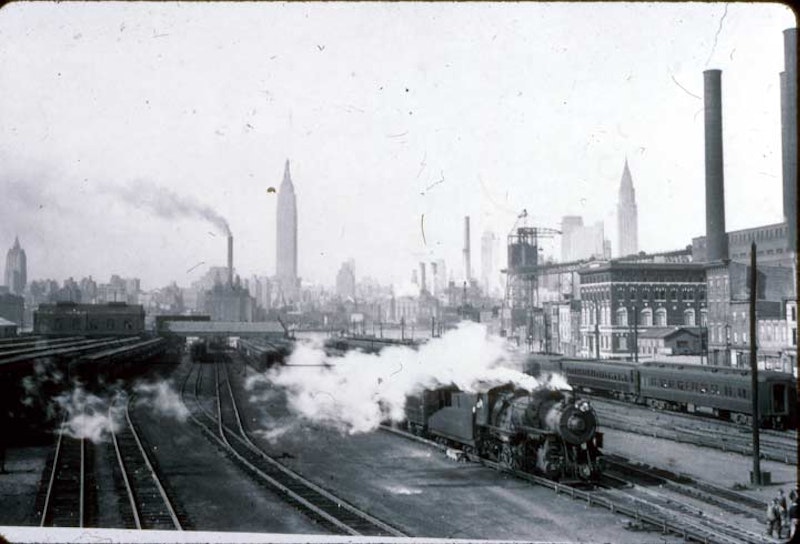

The image at the top of the article depicts the Long Island City railroad yard. Before 1910, this was once one of the largest and busiest rail yards in the world, serving both freight and passenger trains; customers would board the 34th Street Ferry from Borden Avenue to get to Manhattan. All that changed when Penn Station opened and a one seat ride to Manhattan was finally instituted, and trainyard facilities shifted to the much vaster Sunnyside Yards.

In this photo, likely from the early 1930s, s steam engine is bound for Jamaica and some passenger cars are laid up on the right. Back then, skyscrapers were still relatively few and really punctuated the skyline.

This is a look east on 44th Drive, then called Nott Avenue, as it crossed Ely Avenue, now 23rd Street. This was a few years before an elevated train that branched into the Astoria and Flushing Lines was constructed in 1917.

The brick buildings at the left still survive, as does the small house on the right, minus its porch, plus the four-story brick building next to it. 44th Drive still has a center median.

Nott Avenue had honored Eliphalet Nott, president of Union College in Schenectady, NY, who bought land in Hunters Point, subdividing and developing it in 1835.

This building still survives on Jackson Avenue between 23rd Street and the Citicorp Building. Next door was a local office for Keuffel & Esser, a manufacturer of measuring instruments, and it’s that building that has a history that still resonates today.

Keuffel & Esser Co., Hoboken, New York, sold and manufactured slide rules, drawing instruments and other technical supplies. Established in 1884, K&E sold slide rules beginning in 1886, began manufacturing their own rules in 1891 and continued with that business until 1976. Over the course of their history Keuffel & Esser became the largest manufacturer of slide rules in the United States. In 1967, perhaps concerned about the rise of the computer in making calculations, Keuffel & Esser commissioned a study of the future. The report predicted that, by the year 2067, Americans would live in domed cities and watch three-dimensional television. Unfortunately for the company, the report failed to predict that slide rules would be obsolete in less than ten years, replaced by the pocket calculator. By 1976, Keuffel & Esser mothballed its slide rule manufacturing equipment and sent it to the Smithsonian Institution. They transitioned into computer-assisted drawing (CAD) equipment in the 1980s.

There are still a couple of magnificent K&E buildings in the area, on Fulton Street in Manhattan and in Hoboken, NJ. The Fulton Street location incorporates images of drawing and rendering tools in its façade.

The stolid brick Neptune Meter Works Building on Jackson Avenue and Crane Street stood from 1910 until October 9, 2014; it was then razed to make way for a multimillion dollar condominium project, joining many such in the neighborhood and along the Queens waterfront. Neptune, currently based in Tallassee, Alabama, occupied the building until 1972.

The meter works, though, shot to fame in the 1990s when Pat DiLillo established Phun Phactory, later 5 Pointz, in the early 1990s to provide street artists a way of displaying their talents without breaking the law. However, some artists argue that anarchy is a part of graffiti culture, and a legal space circumvents that mission. 5 Pointz was most visible by passengers on the #7 el, which ran behind the building.

This Flemish Gothic structure stood on 30th Street south of 30th Avenue. A different school, IS 235, known as the Academy for New Americans. The original school burned down in 1967 when an 8-year-old kid was playing with matches in a closet and accidentally started the fire. The school was scheduled to be closed and replaced with a new building at the end of that year.

The photo labels the building as being on Academy Street. In the early 20th century, Queens was still largely farmland with a few large towns located within, such as Long Island City, Astoria, and Jamaica, with smaller settlements scattered around; each had their own street layouts with their own individual numbering schemes. As Queens grew and became more populated, the post office was having trouble with duplicated numbers and street names; thus, the Queens Topographical Bureau set to work giving Queens its own particular numbering scheme that was instituted gradually and was mostly in place by the 1930s.

The Queens county Courthouse was originally designed by the architect George Hathorne and built in 1874. A fire destroyed a portion of the original building in 1904, and was replaced with the current Beaux Arts limestone structure in 1908, designed by architect Peter Coco. The famed 1925 murder trial of Ruth Snyder (the smuggled photo of Snyder in the electric chair was a Daily News sensation in 1925) and the robbery trial of Willie Sutton, who robbed banks because “that’s where the money is” were both held here.

In 1910, Coco and 13 others were tried for corruption and grand larceny in the very building Coco had designed. He wound up going to prison for two years.

—Kevin Walsh is the webmaster of the award-winning website Forgotten NY, and the author of the books Forgotten New York and also, with the Greater Astoria Historical Society, Forgotten Queens.