Great to receive the Nobel, sure is, sure is. Actually, Bob Dylan didn’t say that—it’s a paraphrase from his splendid one-hour concert at the Isle of Wight in 1969—and as of this writing, he hasn’t acknowledge the Nobel Committee in Sweden, which fairly ludicrously bestowed the award on the 75-year-old in the category of literature. I hope he doesn’t show up at the ceremony, since that would be a very Dylan move. And it wouldn’t be surprising if he’s a little embarrassed by the attention—although he’ll probably take the dough!—for as The Weekly Standard’s excellent essayist Andy Ferguson wrote this week, almost exactly echoing my sentiments, it’s a stretch to say, as Harvard history professor Cass Sunstein did, that “Like a Rolling Stone” is Dylan’s “Hamlet,” and “Desolation Row” his “King Lear.” Enough!

On the day the award was announced my 24-year-old son asked, after hearing my skepticism, “Aren’t you happy for Dylan?” No, not really, since I don’t know the man. It’s a weird choice—John Barth and Thomas Pynchon, two brilliant novelists have never been so recognized by the benighted committee in Sweden—but par for the course. Almost all awards, whether it’s the log rolling that dictates the Pulitzers (when some of the judges are journalists whose colleagues are nominated it’s fishy), the political correctness that’s affected the Oscars for years, or, and here we devolve, musicians who received Jann Wenner’s blessing for entry into the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame, are kind of a con, if not so consequential. But really, Billy Joel? Let’s remember that Yasser Arafat, Henry Kissinger, and Al Gore won Nobel Peace Prizes—as did Barack Obama in 2009 before he even knew the names of his butlers—and the saccharine Toni Morrison took home the Literature Nobel in ’93. I’ve commented on various social media sites that the Dylan choice was likely, to be charitable, a Lifetime Achievement Award not only for him, but the Baby Boomer generation at large.

I should note that none of the above diminishes one iota my admiration for Dylan: I grew up listening to him in the early 1960s with my four older brothers providing tutelage; Highway 61, at 10, was the first LP I ever bought; several years later, I purchased over 50 illegal Dylan bootlegs, hearing songs that were never released (but would be later, with Columbia fattening its coffers) and heard scratchy versions of The Basement Tapes, the never-completed but haunting “I’m Not There (1956),” and the explosive 1966 concert in Manchester, which might be the best live album ever recorded. Like many, Dylan’s my favorite pop star—even if I fell off that slow train coming once he found religion—and no one comes close. But I’ve never bought the idea that his songs, with a few exceptions, are poetry that can be read without the context of the music and his marvelous voice. I guess that whole “Dylan can’t sing” rag that was so prevalent decades ago has expired, as well it should. You only have to listen to Dylan’s voice on traditional folk songs like “Pretty Saro” and “Copper Kettle” to hear the emotion and passion that’s absent from the antiseptic versions recorded by Judy Collins and Joan Baez, respectively. He couldn’t match the Everly Brothers on “Take a Message to Mary,” but his rendition was wonderful.

Dylan was an ambitious and smart young man who came of age at exactly the right time: no one captured the moving pop culture of the 60s and early-70s like he did, whether it was superseding the folk scene by writing his own songs, cannily forging an alliance with Baez to gain popularity, turning to blazing electric pop in the mid-60s, giving off-the-cuff, hilarious interviews, and firmly rejecting the media’s description of him as the “Voice of His Generation.” Oh, and then there was the cover of Highway 61, Dylan scowling while wearing a psychedelic dress shirt over a motorcycle t-shirt: at that moment, in 1965, there was no cooler man alive.

But as Ferguson writes about “Desolation Row”: “Neither the lyrics nor the tune are interesting to stand on their own. But the tune distracts us from the weakness of the lyrics, and the lyrics give the tune a purpose and direction. Put together with a lovely arrangement, the song becomes an entity that’s larger than the combination of its elements. It’s a genuine achievement. But it’s not Whitman, not Shakespeare. It’s not literature.”

Naturally, I’m particularly partial to certain Dylan songs and lyrics. Such as:

“Now the rainman gave me two cures/Then he said, ‘Jump right in’/The one was Texas medicine/The other was just railroad gin/An’ like a fool I mixed them/An’ it scrambled up my mind/An’ now people just get uglier/An’ I have no sense of time.” (“Stuck Inside of Mobile,” 1966.)

“In the dime stores and bus stations/People talk of situations/Read books, repeat quotations/Draw conclusions on the wall/Some speak of the future/My love she speaks softly/She knows there’s no success like failure/And that failure’s no success at all.” (“Love Minus Zero/No Limit,” 1965.) The last two lines are ripped from a Robert Browning poem, about which I wrote a freshman college term paper, but no matter.

“The drunken politician leaps/Upon the street where mothers weep/And the saviors who are fast asleep, they wait for you/And I wait for them to interrupt/Me drinkin’ from my broken cup/And ask for me to/Open up the gate for you.” (“I Want You, 1966.) This song from Blonde on Blonde, a stunning double-LP, is jaunty and uplifting; and, as often happened before lyrics were accessible, I'd confused the word “saviors” for “azaleas,” and was corrected by a friend a few years later. I still prefer “azaleas.”

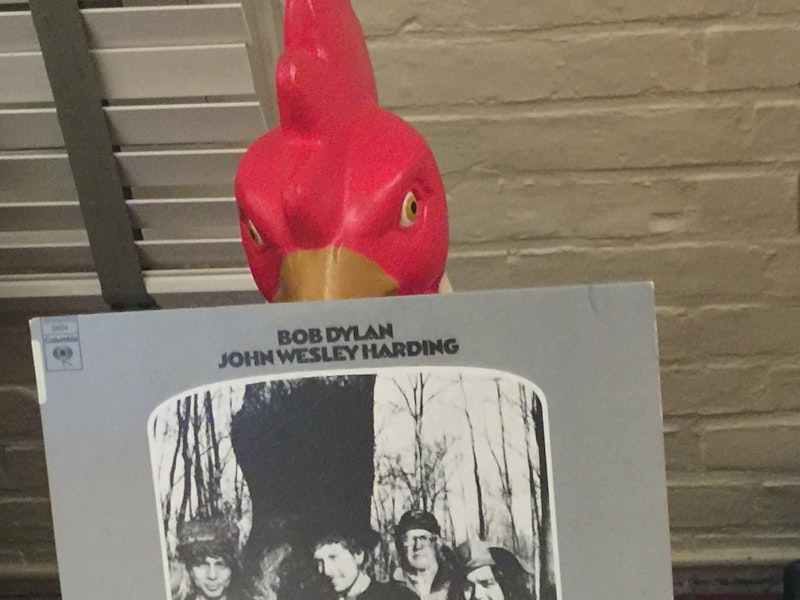

I was blown away by Dylan’s John Wesley Harding, released at the very end of 1967 without any publicity. It was his first record in 18 months, coming after his motorcycle accident in the summer of ’66, which he used as an excuse to calm down after a frenetic five years of non-stop touring, abuse of amphetamines and booze, and staving off journalists and worshipping fans. At the time, Dylan said of the spare, country-like album that it was all he could manage given his injuries, which was baloney, since not long after being laid up with his injuries he recorded almost non-stop with The Band, having a ball singing and writing songs that would end up on The Basement Tapes. The following stanza hit me at the time, and still does, from “As I Went Out One Morning”:

“As I went out one morning/To breathe the air around Tom Paine’s/I spied the fairest damsel/That ever did walk in chains/I offer’d her my hand/She took me by the arm/I knew that very instant/She meant to do me harm.”

It’s a beautiful and cryptic song, enhanced by his new vocal style, but it ain’t Yeats.

—Follow Russ Smith on Twitter: @MUGGER1955