I’ve always liked the increasingly outdated idea of sanctuary—that someone could go into a church or chapel, ask for sanctuary, and receive the protection of the Church from earthly prosecution and sanctions. It existed, to a certain extent, during the Vietnam War, and my father would take AWOL soldiers to sympathetic churches to buy them time and safety from the law.

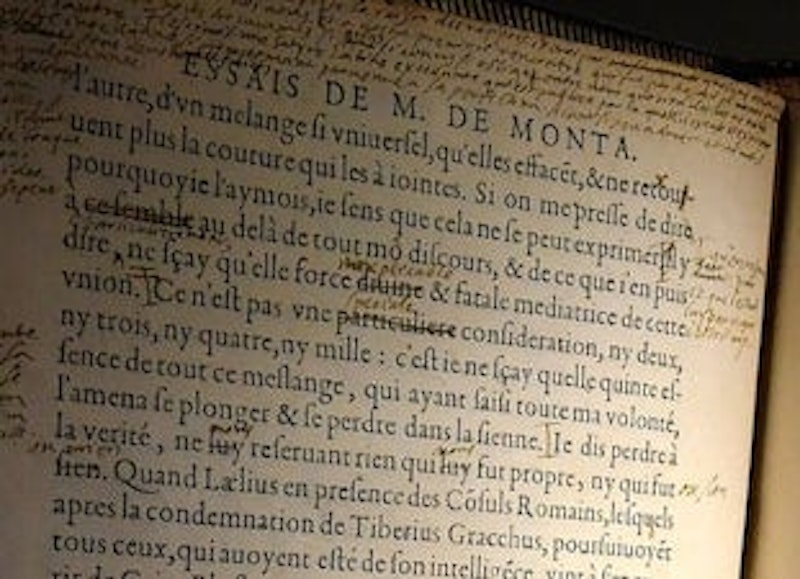

I was looking at Montaigne’s essay “On Punishing Cowardice,” which counts as another in a rather thick cluster of military essays by a man with almost no direct military experience. Montaigne was a member of the French nobility, and as such, he knew how to use a sword and had some tutoring in the history and tactics of war. He was prepared to defend himself and his estate; as it happened, he never had to do so. He didn’t know this would be his lot, however. He lived in the midst of intense civil unrest within France, brought about by the Reformation, and his lifelong political career saw him often trying to bring local disputes to a peaceful resolution. Many of his peers lost their lives in such battles, sieges, and wars.

I’m coming off of a two-week hiatus from “The Montaigne Project” because of legal troubles afflicting my family that wrecked my peace of mind and consumed my attention. After this had been going on for a week, I visited my therapist, who asked me how my writing was going. “It isn’t,” I told him. “I have no time for it right now.”

“Well that’s too bad,” he replied. “Because it seems like writing is the best thing you could possibly do, considering everything that’s happening to you.”

His comment reminded me of something Martin Luther told one of his associates, when his friend said Luther was going to have a very busy day. “In that case,” Martin Luther said, “I shall first have to spend twice as long praying.”

One of the worst ironies of modern pop psychology is that we often try to gather the peace of mind, as if from distant shores, that we imagine we’ll need to do that which is most important and closest to hand. In other words, following Virginia Woolf’s reasonable-sounding advice in “A Room of One’s Own,” we try to locate enough space and time to write, instead of forcing the moment to its crisis by writing in spite of everything. It’s wonderful to seek and find peaceful places wherein one can listen to hesitant, quiet, inner voices and their truths. But it’s also possible to find God in the middle of a battlefield.

After all, it’s nearly a parody of Woolf to imagine Cervantes writing the first part of Don Quixote in “a room of his own”—that is, in a prison cell. But that’s where he did it; a prison cell was also where the breakthrough novels of Jean Genet’s originated. Genet wrote Our Lady of the Flowers on pieces of cloth he was supposed to sew together into purses. A guard found it, realized it was obscene, and had it burned in front of Genet. So Genet started over, with Page 1, and finished it on his second attempt. Then he smuggled his novel out of prison; it found its way into the most exalted intellectual circles of Parisian society and won him a pardon.

Our Lady of the Flowers is, predominantly, a work of extravagant gay eroticism. To read it is to realize that Genet was pushing back against the realities of his existence in prison by daydreaming about violent sexual contraband. He was creating a place in his own imagination that was unbounded and unbarred. Although, just now, I embarrassed everyone in this Montreal restaurant by crying a few public, angry tears about Cervantes’ time in prison, the truth is that nobody who was really confined could’ve written a novel like Don Quixote. And what writer isn’t escaping from jails, and nets, and traps, both inner and outer, every time he starts to work? Who is not taking shelter from death as it whistles overhead?

Sholem Aleichem, as interpreted for Broadway, had this to say about making art out of pogroms: “A fiddler on the roof. Sounds crazy, no? But here, in our little village of Anatevka, you might say every one of us is a fiddler on the roof—trying to scratch out a pleasant, simple tune without breaking his neck. You may ask, ‘Why do we stay up there if it is so dangerous?’ Well, we stay because Anatevka is our home.” The same goes for writing. You might say every writer is a fiddler on the roof. There’s always only a short space between catastrophe and ourselves. To write is to seize it, inhabiting what Jean-Luc Godard once called “a world more in concert with our desires.” But the world as it is, with its exigencies and injustice, remains nonetheless our home.

I have more to say, but the waitress here is gesturing furiously at me. I have already stayed too long. I leave it to you to imagine the rest.

—This essay was inspired by Michel de Montaigne’s 15th essay, “On punishing cowardice.”