Creative nonfiction is tricky. It’s one thing to write a fantasia on a true theme, uniting a poetic style with facts. It’s another to find a structure for those facts that isn’t straight-ahead chronology. Humans live in one direction in the fourth dimension, always forward. Abandon linear time at your peril.

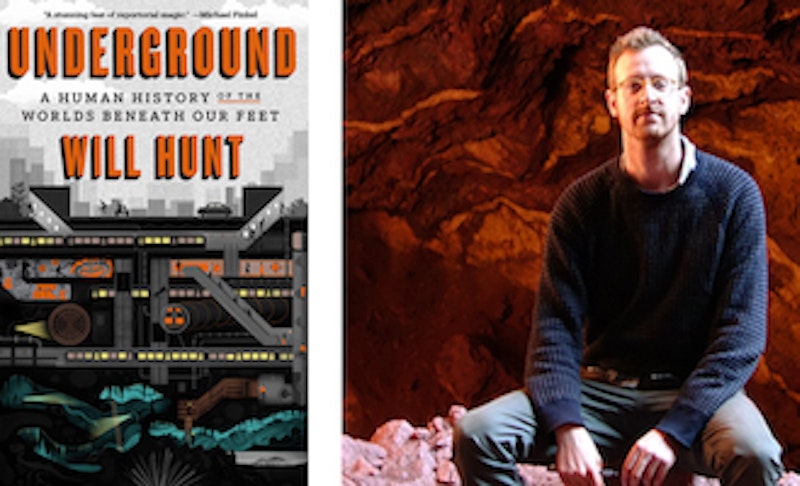

Will Hunt’s approach is a good one. His book Underground is an examination of the worlds beneath our feet; a reflection on what it’s like under the surface of the world, for humans and sometimes for other forms of life. In the total darkness of caves, tunnels, mines, and catacombs, it’s easy to lose one’s place in a labyrinth. Away from sun and stars, it’s easy to lose track of time. Underground therefore abandons linear chronology in place of memoir interlaced with digression.

Each of the book’s nine chapters tells a story of a trip Hunt took through a specific kind of underground space in a different part of the world. Into these personal recollections he integrates stories about where he visits. In this way he’s able to write about French cave paintings and subterranean Cappadocian cities and ancient ochre mines and New York subway graffiti without having to string them all out on a single timeline.

The self-insertion could become precious or even egotistical, and at times Hunt does seem a trifle self-conscious. But on the whole he’s eager to recede, to bring out the greater stories of ages past or of modern explorers. Hunt makes it clear that he’s an enthusiast of the mysterious spaces underground, and if in a sense the book is him trying to figure out what draws him below, it’s also a readable introduction to the many kinds of spaces we tread upon unknowing.

We learn about the Paris catacombs; the vast amount of living things under the earth; the religious history of red ochre; the urge to dig and what it’s like to be lost underground. About the psychic effect the endless dark has on the human psyche. An excellent union of the adventurous and the thoughtful, the book makes plain the risks below the earth’s surface, recounting dangers Hunt found and telling tales of those who didn’t make it out.

But there are also hosts of literary and religious links to the subterranean, references that multiply through the text, not forced but inevitable. We read about psychopomps and shamanic voyages, about Dante and Jules Verne, and these things are only natural. A mortal descending into the earth is an old story. To find mystery or transcendent meaning down below is also old: it’s the tale of Orpheus; it’s the epic of Gilgamesh. It’s a story far older than that, as archaeological discoveries and ancient artworks testify. Hunt’s alive to these meanings, at the same time as he’s fascinated by what is said about them by modern science, whether geology or neuroscience.

It’s important that his structure works not just thematically but as a way to organize information. Each chapter is a working-out of some way of thinking about the world underground. Consider the second chapter: Hunt begins by paralleling his attempt to cross Paris by way of the catacombs with the 19th-century photographic expeditions of Nadar (man of one first name), whose camera first made the catacombs famous. There’s mention of cataphiles and cataflics (roughly “catacops”) who respectively love to wander the underground and patrol the tunnels.

Nadar’s quest for glory gives way to the history of the Paris catacombs; Roman quarries become burial grounds. Hunt’s expedition wanders from main halls (“the Times Square of the catacombs,” as one tunnel is described) to sewer tunnels, facing flood risks, cataflics, and exhaustion. It’s all bound up with references to Orpheus and detailed recounting of 19th-century amazement at the world under Paris: Nadar as Beelzebub, unveiling secrets, setting the stage for aristocrats to wander the sewers and hold concerts among the ossuaries.

The result’s very dense in its presentation of information, but that information’s well-chosen. We’re pulled onwards into the dark by the movement from strange thing to strange thing. The recounting of past times, the nods to rituals lost, acquires a kind of poetry.

Hunt, for the most part, resists poetic diction. There are effective phrases, as when he considers the effect of cave darkness on the “deep, jellied structures of our brains.” But mostly he doesn’t need to extend himself. He’s dealing with a subject almost inherently freighted with meaning: the darkness beneath us, the image of our subconscious and of all the things we don’t know or won’t let ourselves know.

Underground doesn’t pretend to exhaust its subject. There’s always more to explore. Hunt describes his own journeys in the companies of guides, psychopomps—originally a word used to describe the god that guides spirits to the realm of the dead, here human guides to the place where the dead were once imagined to dwell. Writing this book moves Hunt into their company, a guide to the mysterious other realm beneath us, to the shadows and the depths. He’s at it, casting light where there’s light to be cast and hinting at what more there is to say. To describe what is subterranean is to describe human reactions to the subterranean, to the darkness, to disorientation: terrifying and transcendent. Hunt makes this paradox clear and vivid, which is good enough for any book.