Michael Kupperman’s 2018 graphic memoir All the Answers is an unsuccessful book about the misery of success. Fame, notoriety, and acclaim are presented as rigged, fleeting, and traumatic. Yet at the same time the book—inevitably—is attempting to achieve a modicum of the influence and fandom that destroyed its subject. The contradiction is less an irony than a weight, remorselessly flattening writer and written about beneath the same burden of failure.

The comic is the story of Michael Kupperman’s father, Joel Kupperman. Joel was a child prodigy in math who appeared on the radio show the Quiz Kids and later on its television successor starting when he was seven in 1943 and ending when he was 16. Though the show is little remembered, at the time it was a massive popular culture touchstone. Joel and his fellow Quiz Kids sold millions in war bonds. Joel, the most famous of the show’s quizees, met luminaries like Milton Berle and Orson Welles, and appeared in a film alongside Donald O’Connor. His name has been mentioned in Philip Roth novels and Nora Ephron articles.

Lots of people—not least writers and artists—spend their lives in search of a fraction of that notoriety and recognition. But it didn’t bring much happiness to Joel. He was pushed into radio by his ambitious mother, and continued out of a sense of financial and emotional obligation. After he left the show and went to the University of Chicago, he was ruthlessly bullied by fellow students who saw the answer kid as a brown-noser and an irritant.

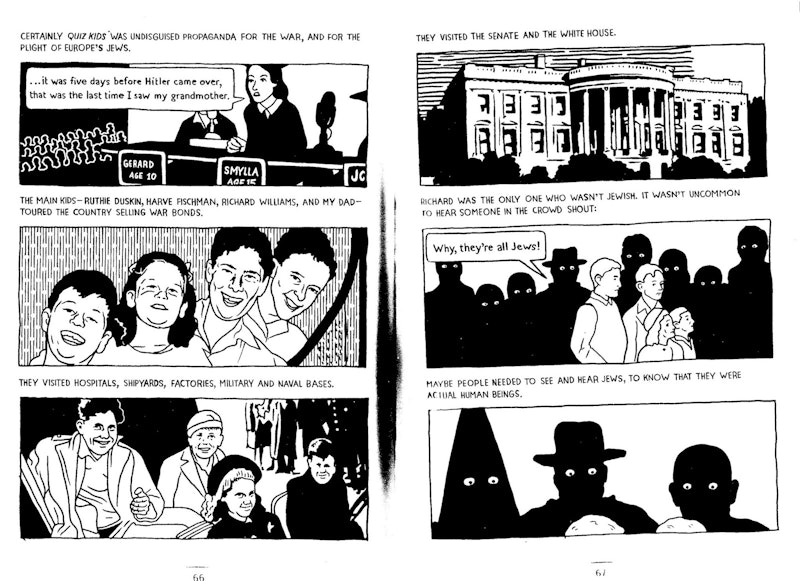

Even worse, perhaps, according to Michael’s telling, was his father’s sense that his successes weren’t deserved. Joel felt that his fame had been “manufactured,” in part by his mother, and in part by Louis G. Cowan, the producer of The Quiz Kids. All of the stars of the show were Jewish; it’s likely that Cowan (also Jewish) was using the children as a kind of anti-fascist propaganda during the wartime. He wanted to show the world that Jewish people were valuable and (in the war bond effort) patriotic.

Joel was good at math. But as a Quiz Kid, he also was encouraged to bone up on other topics—to read Time magazine to be ready for newsy questions for example. In later interviews, his mother said that while Joel wasn’t given the answers to questions beforehand, the questioners knew what topics he was expert in, and they wanted him to succeed. In one later television comeback episode, Joel was given the answers, much to his horror. He quit almost immediately.

Joel felt he was forced to construct a childhood that wasn’t his. And in response, he largely erased it from his memory. Michael tried to talk to his father about his experiences with fame over the years. Joel mostly responded that he had no recollection, either of events or of his own emotional reaction. The book is written as Joel slips into dementia; his mind slips away in an echo, or completion, of his lifelong work of self-erasure.

Michael’s black and white art emphasizes his father’s sense of isolation and emotional distance. The lines are thick and blocky, and the backgrounds are moire dots or patterns. Even when characters are speaking or leaning their heads together, they seem severely separated from one another and from their surroundings. Panels are often separated with text between the gutters, which gives the narrative a disjointed feel.

In comparison with classic graphic memoirs like Art Spiegelman’s Maus or Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home, All the Answers comes across as emotionally unavailable. You don’t feel close to either Joel or Michael. The final line in the book is Michael saying, “For myself and the family, the story needed to be told. Didn’t it?” You’re left uncertain whether the book was necessary, moral or even worth reading. Should we remember when Joel himself didn’t want to?

The sense of estrangement is thematic; the book feels drained of affect because Joel’s fame flattened him out. But what works aesthetically isn’t necessarily always something that works to sell copies. I’m friendly acquaintances with Michael on social media, and he’s spoken there several times about how the book—despite enthusiastic blurbs from Grant Morrison and Jake Tapper—didn’t get the recognition he’d hoped for.

Is it hypocritical to write a book about how success turns to ashes when you want to be a success yourself? I don’t think so. Michael points out that his father did touch many people’s lives; he offered comfort and entertainment in the middle of a war. Connecting with people and bringing them joy isn’t a bad thing in itself.

Popular culture has created a winner-take-all deadlock. You can either speak to everyone or no one—either turn yourself into a product for generating interaction or sink into isolation and silence. You’ve got to have all the answers, this sad, quiet book seems to say, or else you have none of them.