I’d known almost since I began watching it that professional wrestling was a load of hooey. My mom, who took entirely too much satisfaction in dispelling childhood illusions, wasted little time in telling me so. Nevertheless, I derived a measure of solace from the fact that these cartoonish characters were at least musclemen nonpareil. Then I saw Dino Bravo thrill WWE fans by attempting to set a phony bench press record at the Royal Rumble.

Bravo, a skilled middle-of-the-card wrestler from the 1970s who’d eventually wind up shot to death by mafia hitmen, had reinvented himself in the late 1980s by beefing up to play the role of "the World's Strongest Man" in feuds against WWE stalwarts such as equally beefed-up Don "The Rock" Muraco and former football player "Hacksaw" Jim Duggan. "The World's Strongest Man" is a recognizable type in the wrestling commedia dell'arte, and has been performed with great skill by actual strongmen Ken Patera, Bert Assirati, Crusher Blackwell, and Mark Henry.

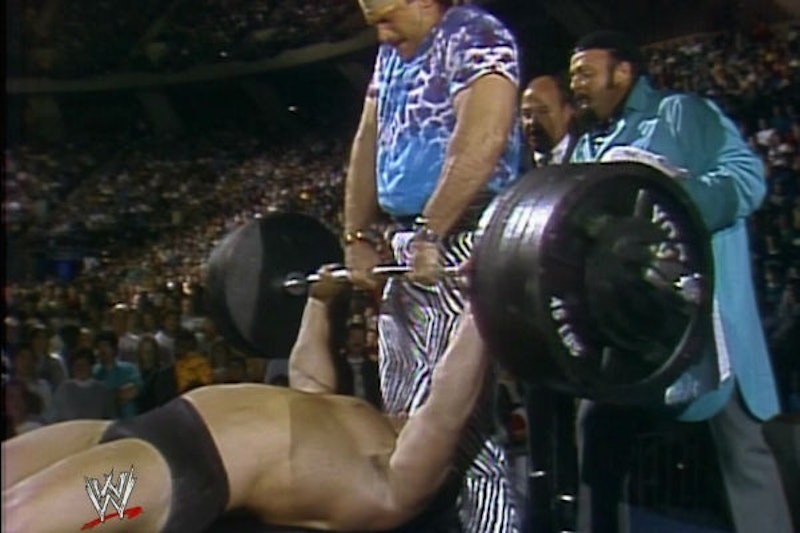

The bloated Bravo appeared out of his element when given a bar loaded with phony York plates and a more-than-generous spot from future Minnesota governor Jesse "The Body" Ventura. I’d just watched my 18-year-old half-brother complete an actual repetition with 405 pounds on the barbell and could still recall my father working with similarly heavy weights during the prior decade. Nothing either did ever amounted to anything close to a 715-pound raw bench—that wouldn’t happen until Scott Mendelson pulled it off in 2006—but none of it looked as stupidly easy as Bravo’s silly weightlifting exhibition, either.

And it was also curious that Bravo was the man tasked with doing this, given that the WWE had once employed Ted Arcidi, a world bench press champion and a behemoth over whom I’d obsessed years earlier. To be fair, Bravo, even in this heftier state, could still sell wrestling moves and give a half-decent interview, whereas Ted Arcidi could barely wriggle his arms on account of all the mass that he had packed onto his dense frame.

Why, 20 years hence, is a forgettable event like this worthy of recollection, much less commemoration? It was, as already noted, a load of hooey, but it’s also extremely revealing hooey. Ever since the so-called "Gold Dust Trio" of wrestling promoters recognized that fans cared much more about exciting outcomes than the glorified clinching contests into which unscripted professional wrestling had devolved by the late 1910s, the sport faced a crisis of legitimacy. Its earliest champions were, in the main, accomplished "hookers" (i.e., men who could actually wrestle), but occasionally burly entertainers like ex-football stars "Big" Wayne Munn and Bronko Nagurski and former boxing champion Primo Carnera were given extended runs at the top of the card. By virtue of their prior success in other activities, these non-wrestlers were capable of selling lots of tickets; however, they were also capable of being pinned by anyone with a modicum of grappling talent. As such, their opponents were under heavy pressure to make them seem like unbeatable monsters.

Competition among wrestling organizations necessitated the creation of ever more outré fictional characters for whom the fans could cheer. Dark-complexioned Italian immigrants became "Wild Men of Borneo," obese college boys acted out the part of illiterate hillbillies, and anybody with a reasonably sophisticated vocabulary and a half-decent physique could find semi-gainful employment as an effete, aristocratic villain. Even real backstories were embellished: college football backups became NFL gridiron greats, Olympic alternates became Olympic champions, and actual Olympic champions became "World's Strongest/Best Conditioned/Most Perfect Men."

When Vince McMahon assumed control of the WWE from his father during the early-80s, he took this practice to new heights. A notorious "juicer" with a body of immense proportions, McMahon was inspired by the work of Joe Weider's International Federation of Bodybuilders to create a roster of pumped-up strongmen with made-up (and trademarked) names and superpowers. Having Bob Backlund, a bland good guy with a solid amateur wrestling background, as world champion simply wouldn't cut it in this brave new world. Instead, McMahon turned to 6'6" bassist manqué and steroid abuser Hulk Hogan, his answer to Weider's similarly larger-than-life Arnold Schwarzenegger. Much as Schwarzenegger never claimed to be anything but a bodybuilder, Hogan was never anything besides an extremely limited professional wrestler. Both men, however, proved adroit at seeming "hard" and "masculine," an ability that brought them great success during a decade characterized by superficiality and excess.

"A culture that idealizes, fetishizes, is addicted to the hard and impenetrable," writes Susan Bordo in The Male Body, "is a cold and unforgiving place to be." I grew up in this culture, and did everything I possibly could to avoid being perceived as soft or weak. My father was hard and impenetrable, and he ruled with an iron fist. Ours was a household dedicated to the ideal of his strength and dominance. "Boys," Bordo continues, "are ashamed to tell others when they are injured; the simple act of telling is an admission that they are not bearing their pain 'like a man.'" My half-brother and I became strong not to cow our peers—we were usually (regrettably) the ones doing the bullying—but to protect ourselves from the pain our father caused.

We needn't have bothered. Much like the Dino Bravo bench press, much like the dozens of Olympic also-rans who were billed as Olympic champs, our father's strength, though certainly still real in some tangible sense, was not what it once had been. His business consumed nearly all of his time and energy, he was aging, he was unhappy... what we perceived in him was what, in caricature, Vince McMahon and Joe Weider sold to their viewers: a façade of strength, and nothing more. He was flappable to a tragicomic degree, his mind a roiling ocean of anxieties and horrifying childhood memories. He, too, had nothing for protection but his remaining illusions of hardness.

The critic Roland Barthes claimed to admire professional wrestling because it provided the spectator with clear and distinct signs: the good guy was unimpeachably good, the bad guy was incorrigibly bad. Although the Attitude Era forced an adjustment of that paradigm, the signs remained clear. The massive bodies, the manufactured backstories, the obvious deceptions (try to imagine middle-aged Hunter Hearst Helmsley or jorts-wearing John Cena actually vanquishing MMA champion Brock Lesnar!)... this endeavor is in many respects the very embodiment of male overcompensation and male insecurity. The participants, no longer necessarily "good" or "bad," still vindicate their phony hardness in pitched, scripted battles.

When I watch pro wrestling nowadays, I find my thoughts drifting inward. Are we men all, I wonder, nothing but poseurs? On that score, wrestling has one final lesson for us. For many years, in order to maintain the original "kayfabe" myth, promoters paid fees to state athletic commissions that regulated professional wrestling as a sport. In the course of revamping his father's federation as a "rock and wrestling" outfit for the MTV generation, McMahon stopped paying his dues to these organizations, explaining that he was in the entertainment business. His matches might feature feats of athletic derring-do, but they assuredly weren't sporting exhibitions.

This admission, though little more than a historical footnote, is nevertheless fascinating. McMahon conceded that he’s in the business of peddling obvious falsity to the multitudes. He’s an honest liar, thoroughly shady and corruptible in all respects, and it doesn't matter if you're in on the scam: after all, his best and most tasteless WWE-verse jokes are on you. Just buy the t-shirts, the programs, the pay-per-views, the commemorative cups and life will go on as always.

Moreover, serious fans view this truth/falsity stuff as irrelevant. They watch the matches for the quality of the performance: the truth, in their opinion, is arrived at only through a careful evaluation of the act of pretending. The most noteworthy example of this approach to professional wrestling was postmodern grappler C.M. Punk's famous "worked shoot" promo, which catapulted him to the status of the most important man in the WWE who wasn't John Cena. The promo was "worked" in the sense that it was part of a storyline in the fictional WWE-verse; it was a "shoot" in that Punk had aired some actual criticisms with Vince McMahon's jort-loving, Cena-centric approach to booking.

It’s here, I believe, that we find an answer to the airy and undoubtedly Gen-X question, "Are we bros just a bunch of poseurs?" Punk lays it on the line: yes, my work is a load of bullshit, but some of us are better at this bullshit than others. For those of us mature enough to recognize the difference, feigned "hardness" is true or real insofar as one can perform well in such a "hard" role. In my teen years, I once criticized a renowned professor for being a person who could simply "recite a good script" during his lectures. But now I realize that, yes, of course that's all he did—the man wrote the script, for crying out loud!

When you're young and stupid and scared in a society that insists that you "be a man"—whatever that actually means—you sometimes find yourself claiming to be way more than you are. You say you've heard of bands that you know nothing about, you purport to lift weights far beyond your Mr. Puniverse skill level, you pretend to have read the great books that any hip scholar worth his salt should have already tackled... and then one of three things eventually happens: you keep lying about having done this stuff but don't ever accomplish any of it, you never do it and focus on doing things you actually care about, or you do it and refuse to look back.

As C.M. Punk's improbable rise to the top of a profession dominated by muscle-bound pretenders demonstrates, it's possible to fake it until you make it. Come to think of it, is there any other way? "Being a man" may at first entail a great deal of self-deception in response to gendered social pressures, but at a certain point along the haphazard highway that leads to mature contentment, it comes to mean nothing more or less than "being yourself."