Rereading books has both its risks and rewards. If you get lucky, the years will have given you an improved perspective that makes the second go around an even better experience. Subtleties that you may have missed might reveal themselves after a couple decades of life experience. If a book was such a delight years ago, then why not read it again, after you've put it down for enough years to make it seem fresh again? I've had this experience several times, with such writers as John LeCarré, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Cormac McCarthy.

On the down side, there's an opportunity cost involved when you revisit the past in this way. You're only going to be able to read so many more books in your lifetime, so picking up an oldie means a delay for those books that are on your “to be read” list.

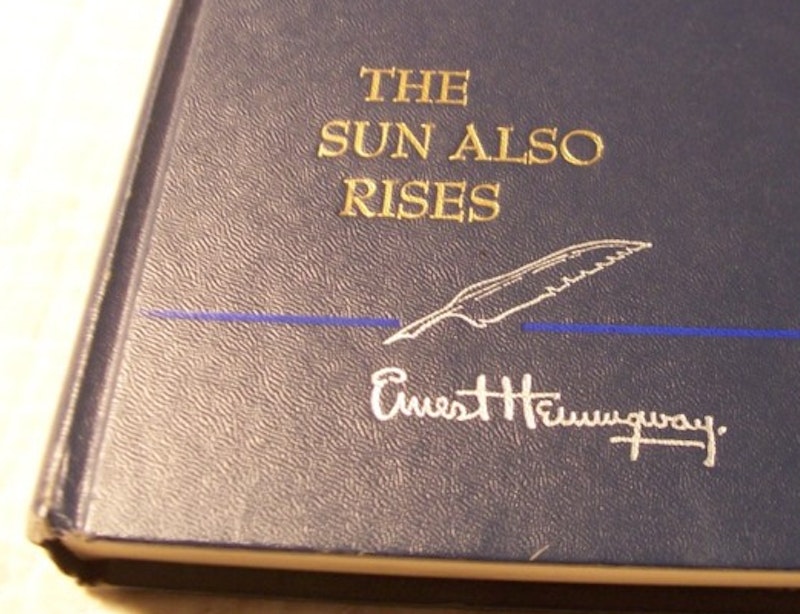

I recently reread Ernest Hemingway's The Sun Also Rises, the first time since college. At the time, the settings of the novel, first in Paris and then Spain, lent the story an attractive, exotic quality. Plus, it was written by the legendary man of action himself—a man's man who’d been to war and run with the bulls at Pamplona. The Hemingway persona was so towering that it lent its own cachet to anything with his name on the cover. Still, the book never left a burning impression on me, like Catch-22 or One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest. I've never thought of it as a particularly great novel, and only picked it up again because I found it in a neighborhood Little Library. Maybe I'd missed something the first time, I thought.

That isn't how things worked out. Once again, it failed to grab me. There's an aimlessness to both the story and its characters, who spend the majority of their waking hours drinking heavily and engaging in pointless banter. Yes, it's intentional, but it still does little for me. The characters are from what Gertrude Stein dubbed the Lost Generation. Horrifying memories of WWI have left them traumatized and in need of numbing agents. The narrator/protagonist, Jake Barnes, and his not-so-merry band of drinking buddies that includes one fascinating woman who’s ahead of her time—the heartbreaker, Lady Brett Ashley—drift from the Cafe Napolitain to Foyot’s, and then on to Braddock's, the Cafe Select, or the Rotonde. They have a “jolly good time” drinking their brandy and soda, champagne, dry sherry, absinthe, vermouth, beer, port, Pernod, martinis, and a lot of wine. They get “tight,” or even “blind,” some of them on funds of unclear origin, whether they're on the Boulevard St. Michel or in the dining room of a Spanish hotel catering to bullfight aficionados.

The fact that none of the core characters are particularly likeable is a problem. That one of them, Robert Cohn, who’s everyone's object of derision, is seen as even less attractive because he's a Jew is troublesome. “Well, let him not get superior and Jewish,” is how Jake Barnes’ buddy Bill speaks of him. Later on in the story he says, “That Cohn gets to me. He's got his Jewish superiority so strong he thinks the only emotion he'll get out of the fight will be being bored.” But this Jew, even though he knows how to use his fists, fails Hemingway's ultimate test of masculinity because the bullfights make his stomach queasy. And even though Cohn has enough going for him to entice the Anglo goddess, Lady Brett Ashley, into a brief affair, it ultimately leads to his disgracing himself in the most humiliating manner. Cohn becomes a physical bully who then cries after beating people up, after which he has no choice other than self-exile from the group.

Cohn is everyone's punching bag. A peripheral character, Harvey Stone, calls him a “moron” right to his face early on in the story, and Cohn just takes it. Brett has no use for him after their fling, and her new man, Mike, is a broke drunkard who showers Cohn with abuse for hanging around and mooning over Brett. Jake Barnes also has little use for Cohn, and at a certain point one has to wonder why the group chose to have him around.

To feel the impact of The Sun Also Rises, it's necessary to accept Hemingway's premise that bullfighting is the most noble of pursuits. Even though Barnes isn't able to consummate his love for Lady Ashley due to his unspecified war injury, he's still a real man because he has aficion for the bloody spectacle. He's passionate about the purity of bullfighting culture. The young bullfighter Romero’s irresistible to Lady Ashley, and when Cohn beats him to a pulp in a jealous rage, he’s still noble enough to drag himself off the floor to punch his weaselly assailant, who has no aficion whatsoever, in the face.

I also lack bullfighting aficion, maybe because I'm not obsessed with death as Hemingway was. It wasn’t just a sport to him. The author witnessed the deaths of 1,500 bulls and found it a meaningful experience each time. If I could understand why this is, I'm sure I'd get much more out of The Sun Also Rises. That's the risk of rereading books. The next time, I'm going to lower the risk factor by making sure it's a book I loved in the first place—maybe Catch-22, come to think of it. The Sun Also Rises has one great line in it. When Bill asks Mike how he went bankrupt, Mike replies, "Two ways. Gradually and then suddenly." Coincidentally, that also describes how I realized I probably shouldn't have reread this novel.