Last Friday, I went to Baltimore’s Parkway Theatre to see Tony Conrad: Completely in the Present, Tyler Hubby’s new documentary on the late experimental multidisciplinary artist. I had only a passing awareness of Conrad’s work before he died last April—and I remember dozens of people here in Baltimore sharing footage and remembering his solo performance at High Zero in 2008. I’ve done some digging since, and what’s out there is fantastic, especially Four Violins (1964) and Slapping Pythagoras, an album he made in 1995 with Steve Albini and Jim O’Rourke. But there’s always been a significant gap in Conrad’s body of work because of preeminent prick La Monte Young. Someone needs to tie him up and raid his archives and free all that music that was meant for the world to hear—or at the very least, the people that created it. The man is holding onto, in John Cale’s words, “an entire body of work” by The Dream Syndicate (Young, Conrad, Cale, Angus Maclise, and Marian Zazeela), reels recorded from 1963 to 1965 that mark some of the earliest examples of American minimalism in music.

Despite the film’s title and primary thrust—that Conrad was a kinetic and prolific artist, never satisfied to stay with one thing too long before destroying it—it dwells on Conrad’s righteous dispute with Young and his inability to access and share those Dream Syndicate recordings. Everyone’s on his side—Cale is equally aggrieved and frustrated by Young’s delusional and narcissistic insistence that he was the “sole composer” of those improvised sessions. When someone finally found a bootleg of one of the reels and gave it to Jim O’Rourke in the late-1990s, Conrad, Cale, and the rest of The Dream Syndicate released it as Day of Niagra, against Young’s wishes.

I went to Young's Dream House in Tribeca about six years ago and saw him perform. It was pretty amazing—Young chanted, sang, and droned with two or three women for an hour or so, and in that small, very hot purple room, I heard voices phase naturally for the first and only time in my life. This is before I knew Young got off on deprivation, and in retrospect, it was all very messianic: Young came out 20 minutes after everyone else, wearing a wizard’s hat and carrying a big wooden staff. Maybe if I knew his history then, I might’ve gotten Rooster Quibbits to slip him a note. “Get over yourself, schmuck. Think of the kids.”

Completely in the Present spends so much time on the past, and specific events, that it diminishes its own thesis, even though Conrad’s anger and frustration is justified and understandable. It’s all a bit of a drag, honestly. Hubby’s film is not a memorial, and even though Conrad didn’t live to see it finished, there’s no indication of ill health, disease or looming death. Knowing that grouchy graybeard La Monte Young walks the Lower East Side barefooted while Conrad is gone kind of sucks, especially since the majority of those Dream Syndicate recordings are still locked away. Despite the injustice, Conrad continued on, making films and music and teaching in Buffalo for many years. In the 1990s, he worked with a new crop of young avant garde composers and musicians that bowed to him. He’s gracious and hilarious, and the most frequently interviewed subject in Hubby’s film—very much alive here, completely in the present.

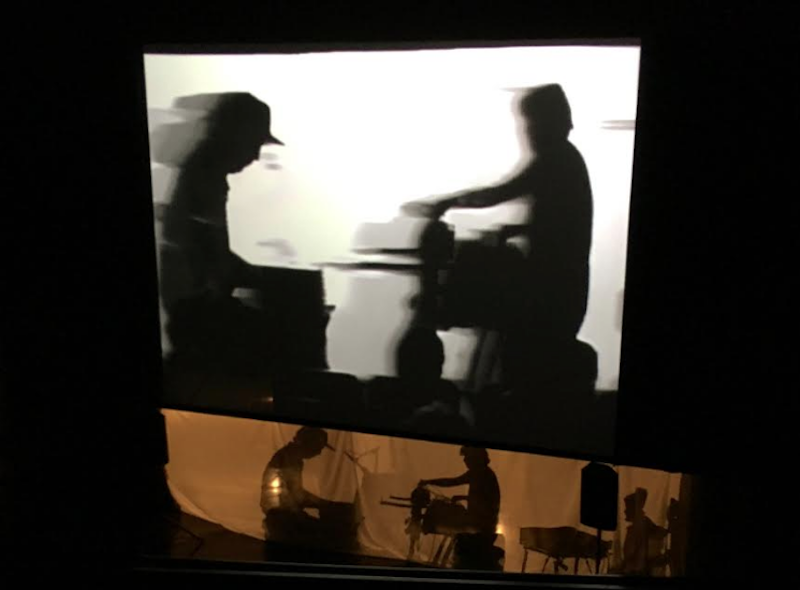

The event was the first of two nights curated by Josh Dibb (Deakin) and Brian Weitz (Geologist) of Animal Collective. After the movie screened on both nights, half a dozen musicians played backlit behind a white sheet underneath The Parkway’s screen, as Greg St. Pierre performed live video manipulation of their looming shadows projected onto the big screen. On Friday, the performers were Steve Strohmeier, Owen Gardner, and Dibb & Weitz, all playing pieces inspired by Conrad’s work. It was astounding, and the first time I’ve seen any musical performance in the Parkway. I doubt a rock band would sound good in there, but just like 2640 Space, anything without drums and loud guitars sounds incredible. There were extra speakers set up in the balcony, and I flipped between nodding in place with my eyes closed and staring at St. Pierre’s glorious live video art, angular high contrast black and white forms morphing into refracted light and dirty rainbows around the shadow profiles of the performers.

Some cosmic joke on me, and a lesson to take this movie’s subtitle to heart: I brought a little digital recorder to tape the sets. The whole show was continuous, and I must’ve had my eyes closed for most of Strohmeier’s set, because by the time Gardner came out and played spartan cello, I didn’t know who was who. When Dibb and Weitz came out, I checked my recorder, adjusted the levels, and pressed stop and started a new track. Or at least I thought I did. For now all but the first minute of Dibb and Weitz’s contribution to the night has been lost to the void. I hope someone else was recording.

Dissonant as the thesis and content of Completely in the Present is, it’s a necessary document of a fascinating and important multi-disciplinary artist that got screwed in a lot of ways and remains comparatively underappreciated among the artists he worked and bumped shoulders with through the second half of the 20th century.

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @MUGGER1992