Joseph Napolitan, the world-renowned political consultant who helped to elect presidents, prime ministers, governors, mayors and lowly town councilmembers, had a deep connection and profound influence on Maryland politics.

Napolitan, who died Dec. 2 at 84 of prostate cancer and Alzheimer’s disease, took politics out of Maryland’s backrooms and clubhouses and put campaigns on television and radio to engage the voters based on the findings of his elaborate and detailed political polls. His presidential clients included John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B Johnson and Hubert H. Humphrey. Napolitan’s Maryland candidates were Marvin Mandel, Blair Lee III, George Russell and Rep. Tom McMillan.

“I only work for Democrats I like,” Napolitan often said.

Napolitan came to the attention of Mandel by way of Dr. Edgar Berman, the dilettante Baltimore doctor and misogynist who had been traveling with Humphrey’s campaign entourage in 1968 as the presidential candidate’s personal physician.

“See if you can get hold of Joe and find out if you can get him down here to talk about working on the campaign,” Mandel said. That was in August of 1969, when Maryland’s first Jewish governor had been chosen by the General Assembly eight months earlier to succeed Spiro T. Agnew and was preparing to face the statewide electorate for the first time in 1970.

I located Napolitan at his summer home on Martha’s Vineyard where he usually spent the month of August winding down from 11 months of traveling the world as a political consultant, the phrase he coined on the spur of the moment to describe what he did when Lawrence O’Brien recruited him to work as pollster and political strategist on Kennedy’s ’60 campaign.

Napolitan told me that he was getting out of the business of managing domestic political campaigns so he could concentrate on foreign candidates that he eventually would advise in 20 countries around the world. I swung into full-grovel mode. I explained that I had promised the Governor that I would convince him to at least meet and I feared that I might lose my job (as press secretary) if I failed to deliver. Napolitan relented and agreed to come to Annapolis.

It was romance at first sight. Napolitan was captivated by the savvy Mandel and his staff of canny operatives and Mandel was impressed with Napolitan’s ease and directness as well as politics-as-science that Napolitan had pioneered as one of the nation’s pre-eminent pollsters and strategists. Napolitan’s polls for Mandel were as thick as phone books and rich with demographic and intricate details on voter attitudes on every issue, personal and political, that the Mandel campaign would face.

After the results of one poll were tabulated, Napolitan observed: “I’ve polled in every state in the nation and there’s no place in this country that is more conservative than the Eastern Shore of Maryland.”

Napolitan’s great skill was translating polling results into campaign and media strategy. To execute the media campaign, he recruited Tony Schwartz, his long-time collaborator, who had developed the famous “Daisy” commercial for Johnson’s 1964 campaign; Jacques Lowe, Kennedy’s White House photographer; and Robert Squier, the television producer for the Humphrey campaign. They were supported by Mandel’s campaign treasury of more than $1.2 million, and more to come as needed, an obscene amount of money at the time.

Maryland had never seen or heard anything like it: A slick, four-color magazine-size brochure, a showcase for Lowe’s photography; a bombardment of radio commercials by Schwartz that helped to convince R. Sargent Shriver, the Kennedy brother in-law, to abandon his challenge of Mandel in the 1970 primary; and a blitz of television commercials produced by Squier to highlight Mandel as a problem-solver who was in tune with the average Marylander. Napolitan ushered in Maryland’s first truly modern television-age, poll-driven campaigns, supported by the skilled statewide political network that Mandel had assembled.

Napolitan’s signature piece was the half-hour biographical film, an idiom that he had pioneered and used to lethal effect against adversaries in other campaigns. Squier delivered an Emmy-quality celluloid epic. It remained unseen and in the can for various reasons. One afternoon I received a call from W. Dale Hess, a Mandel confidante who resigned from the House of Delegates to help manage Mandel’s campaign:

“Let’s run the thing once and see what the reaction is,” Hess said. The biographical film ran on WHAG-TV, in Hagerstown, at 2:30 on a Sunday afternoon. The station was swamped with calls asking when it would run again. It never did.

Napolitan had helped to elect Maryland’s first—and the nation’s only—Jewish governor when the doubters said that it could never be done in a state that had banned Jews from holding public office until 1824 when a Roman Catholic led the fight to repeal the law. Napolitan went on to help elect two more Jewish governors, Milton Shapp of Pennsylvania, and Frank Licht of Rhode Island.

On the day after the 1970 primary, Napolitan and I met with campaign representatives for Sen. Joseph D. Tydings, who was facing a difficult general election, to discuss ways the two campaigns could pool resources. Yet for some unspoken reason, the Tydings campaign resisted symmetrical efforts despite Mandel’s warnings that they were making a major mistake.

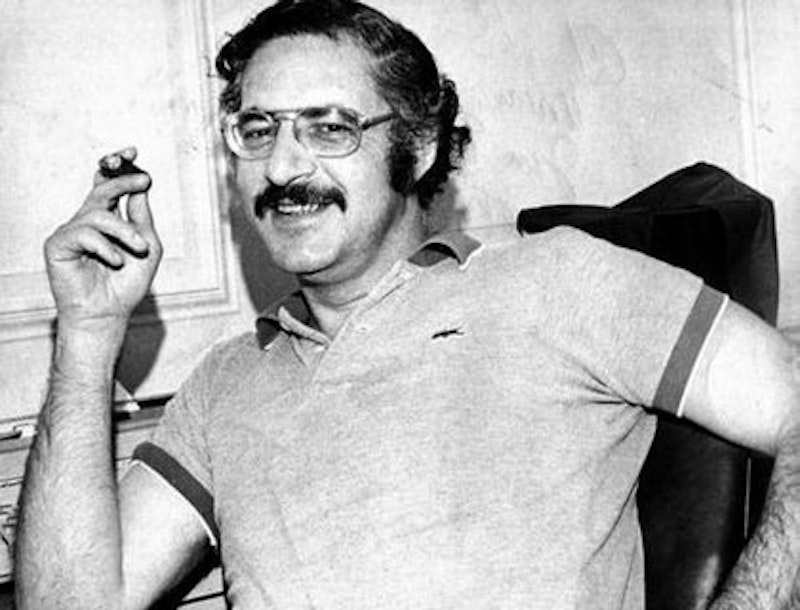

Al Salter, of Baltimore’s Doner Advertising Agency, who was in charge of Tydings’ media campaign, said: “Well, the senator’s victory will be a great help in getting Governor Mandel elected.” At that point, Napolitan closed his notebook, leaned back, lit an ever-present cigar and said very few words after that. Mandel was elected overwhelmingly; Tydings was defeated by Republican Rep. J. Glenn Beall Jr.

Mandel’s 1974 reelection campaign was a reprise of his earlier victory with the same media team virtually intact only on this outing the governor’s very public divorce and re-marriage to a woman 18 years younger than he presented new challenges to Napolitan and his team. Napolitan’s polls showed strong disapproval of Mandel’s abandonment of his wife of 31 years but at the same time a favorable view of his performance as governor. Nonetheless, Mandel was reelected to a second term by a solid majority.

Also in 1974, Napolitan quietly assisted the first campaign of Sen. Barbara Mikulski for the U.S. Senate. Mandel was fascinated by her uproarious performance on the stump, kind of like the warm-up before Sinatra, and viewed her as a campaign asset. Napolitan included her in Mandel’s polls and offered strategic advice. She won the primary that year but lost the general to Republican Sen. Charles McC. Mathias Jr.

In 1971, George Russell, who had peerless credentials as an attorney, city solicitor and judge, decided to run for mayor of Baltimore. Russell is black. Russell had chosen Jim Lacy, a star collegiate basketball player and local legend and a popular figure in political circles, as his running-mate for City council president.

Russell contacted Napolitan. I told Napolitan he would be up against the entire Mandel political organization that was supporting William Donald Schaefer for mayor and had been considering backing Walter Orlinsky to succeed Schaefer as City Council president. Napolitan, nonetheless, saw a challenge and an opportunity in working for one of the first blacks in America to run for mayor of a major city.

In September, 1971, Napolitan and I crossed paths in San Juan, P.R. I was there for the annual meeting of the National Governors’ Association as an aide to Mandel and Napolitan came, coincidentally, to advise the reelection campaign of Puerto Rico Gov. Luis A. Ferre. Baltimore’s mayor election was also being held that week.

Napolitan said: “Russell’s down the tubes but Lacy’s going to win.”

I said: “I disagree. Orlinsky’s going to win [the City Council presidency]."

Napolitan said: “The polls say Lacy. I’ll bet you dinner tomorrow night [after the election] at Zaragozana [a legendary restaurant in San Juan’s Old Town].”

There was no way Napolitan could have known the information that I was privy to. That afternoon I had overheard a phone conversation between Dale Hess, in Mandel’s suite, and Irv Kovens, in Baltimore, in which Hess told Kovens to release $5000 in walk-around money to State Sen. Rosalie Abrams to deliver votes for Orlinsky in her Northwest Baltimore precincts. It was Napolitan who taught me that the one thing polls cannot detect is organization support. Dinner is always more enjoyable on someone else’s credit card.

By the time Blair Lee ran for governor in 1978, I was out of government and president of the advertising agency that had handled Mandel’s campaigns, and now Lee’s. Lee had been on Mandel’s ticket as lieutenant governor and witnessed the political operation in full force.

We assembled virtually the same team for the Lee campaign but the chemistry just wasn’t right and the karmic vibrations collided. Lee and his advisers resisted many of the suggestions that Napolitan proposed. Napolitan asked after one of his regular visits: “Does he [Lee] understand what we do”? Lee lost the election and Napolitan was happy to get out of town. He later told me that Lee’s campaign was the only one that had ever “stiffed” him for fees.

In February of 1972, Mandel hosted the nation’s Democratic governors for their annual conference and booked Napolitan as the principal speaker. Napolitan delivered a prescription on how he thought George McGovern could win the presidential election—ignore all the states where McGovern had no chance of winning and concentrate all of the Democrats’ money, media and firepower on 15 states that added up to an electoral college win. The governors whose states were to be bypassed were outraged and booed Napolitan out of the room. Napolitan had the last laugh in November of that year.

Napolitan’s 1972 book, his lovesong to politics, The Election Game and How to Win It, became a tactical manual for future generations of political consultants and campaign managers as well as the organization Napolitan founded, the American Association of Political Consultants. A good chunk of the book is devoted to the techniques employed in Mandel’s winning 1970 campaign.

The ad for the book that appeared in The New York Times over Mandel’s imprimatur reads: “It is quintessential Napolitan—tough, honest, lucid, analytical, decisive, opinionated, relentlessly practical yet laced with a lifetime’s romance with politics and politicians… If, as Joe Napolitan writes, Machiavelli was the first new politician, then surely Joe Napolitan must be the second.”

The inscription in the dog-eared copy on my bookshelf reads: “To Frank DeFilippo—A good friend and a great press secretary. Joe Napolitan.”