I used to work in an office. It was badly run, so politics was everywhere. The managing editor plotted against the editor-in-chief. The assistant managing editor sniped at the managing editor; the managing editor sniped back, vigorously. People clustered in gangs, a big one and a small one, and they whispered and kvetched. It was a miserable but interesting time.

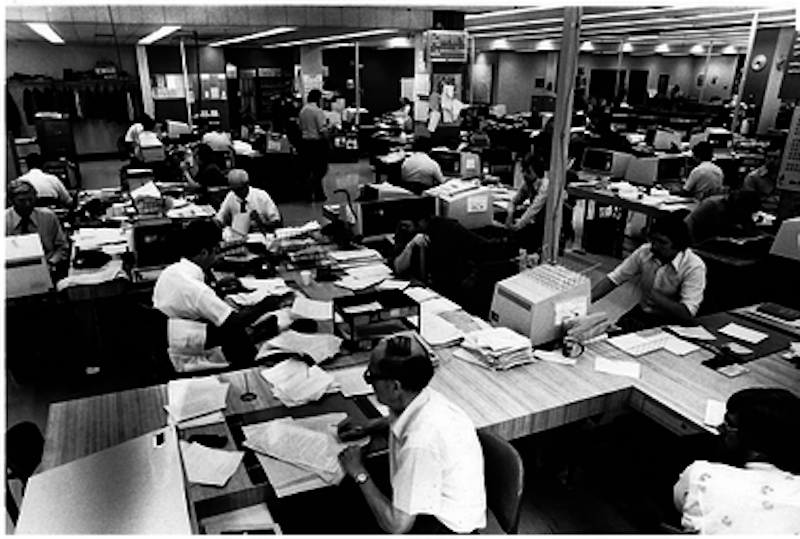

The big gang was very big indeed. It was made up of the managing editor and every reporter in the paper's New York office (which is where everybody mentioned in this story worked). The art director belonged to it, and so did two of the copy editors. The small gang, on the other hand, was really just the assistant managing editor, the chief copy editor and me, the deputy copy chief. I wasn't much of a member. To my mind, the key fact about life in our newsroom was that I didn't belong there. I won't go into this side of things, but basically I was so shy that I made everyone else nearly as uncomfortable as I was.

I sat next to a member of the big gang, a character I'll call Jim. The two of us were friendly for quite a while. He was a sweet fellow and wanted very much to be loved. But he was also a slob. Most of us were about 30 or so, an age when people who were fit can find that now they are fit no longer. In Jim's case this change had taken the form of a landslide. He was a big guy with broad shoulders, but his gut traveled a long way out in front of him. He also had a clam-like complexion, and his collar and tie were generally pointing in unexpected directions. Jim didn't like to exert himself. In fact he confided to me, as a by-the-way thing, that he was a copy editor because reporting took too much effort. You had to run all over town and a copy editor could just sit in one place.

The ethos of our paper, and especially of the big gang, went in the other direction. Reporters were supposed to be young and keen, not young and dilapidated. The boys (they were all boys) had flat stomachs and ironed shirts and ties that lay flat down their chests. Most of the boys, anyway. Our top reporter was big and heavy, and so was the managing editor, but they were bear-like. Jim was more a failed version of somebody lean. He was also a failed version of somebody active. He talked about getting in shape, about his rich out-of-office life, about his disdain for the passive. But at home he sat around and played computer games, and at the office he lurked in the coffee room and bitched about the boss he and I shared, the decent and conscientious fellow running the desk. Jim's nose was especially out of joint when the copy chief placed an ad for a senior copy editor. Jim had been on staff eight months, so why wasn't he a senior copy editor? “Promote from within,” he told me. Then, sagely: “That's how they do it in Japan.”

I mentioned that Jim wanted to be loved. Everybody needs to belong, but he needed it the way a five-year-old boy needs a rest room—he was bursting. And he did belong, but his spot was well down the totem pole. His one advantage was that the managing editor liked him. Of course, the managing editor liked anybody who took his side, but Jim was one of his special puppies. I think Jim's neediness did the trick. Jim worshiped the managing editor, considered him a savant and mastermind. The man's wizardry wasn't confined to journalism, an area that floated just beyond Jim's interest. His real gift, in Jim's view and in reality, was for office politics.

This didn't strike either Jim or me as second-best. Here we enter into the realm of wish-fulfillment. I'm just finishing the latest Robert Caro book about Lyndon Johnson, and it's a treat. Nobody matches him at capturing the drama of politics seen as the clash of giant personalities struggling for dominance. Caro’s so good at bringing events and people to life, at fleshing out the details that demonstrate how remarkable these people were, that it takes you a few volumes to notice something. Here it is: They did on their scale what we do at the office. The first book in the Johnson series shows us young Lyndon as a titanic desk jockey, the Paul Bunyan of administrative paperwork. His other activities, from the first book to the latest, also have a familiar air. Campaigning and backroom conniving aren't too different from life at the typical white-collar work place. You put on your face, you keep your ears open, you see who likes whom and who doesn't, and you figure out what it all means for yours truly. At a dysfunctional office, an office like mine, you do a whole lot of these things.

We worked at a trade paper that enjoyed a decently profitable niche. We had a few bureaus, but the place definitely wasn't big-time. The managing editor and his crew spent a good deal of energy convincing themselves that this was all very exciting, that they were a go-for-it bunch and their lives were a beer commercial that happened to involve computer terminals, two copy machines and the dullest sector of the U.S. financial markets. I think politics, big-time politics, helped them add some gloss to their situation. The kids didn't read Caro or much else, but they did have their political allegiances and followed the news. The managing editor was a politics and history buff, and an idea drifted about the office that this was the sort of thing people ought to be interested in. So when they put their heads together and plotted, they were doing what the big boys did.

I remember that Jim, my seatmate, let me in on some inside stuff from the managing editor. Our top editor, the editor-in-chief, was a gentle, inoffensive little man who happened to be very good at writing and editing but who spent most of his time locked away in his office. The managing editor was the charismatic leader. One day I observed that our supposed top boss didn't seem to carry much weight. Uh uh, Jim said. No, the editor-in-chief was quite the player in corporate politics. Jim said he knew this because the managing editor said so. It was the kind of thing the M.E. told the gang over beers, and it was a bit of a production. Jim trotted me through it, the M.E.'s spiel about the Soviet politician (this was all very long ago) who said Mikhail Gorbachev had a nice smile but steel teeth, and through the follow-up assertion that our editor, blinking and mild as he appeared, knew how to throw an elbow and get his way when the executives gathered. Jim gave no examples to back up this idea. What counted was the business about Gorbachev and his teeth, the allusion. It dressed matters up.

Not long after our talk a change became evident. The big gang began leaving for beers on most evenings instead of just Friday evenings. The members also became noticeably more polite to the little gang. That was a relief, especially since Jim and I were no longer getting along—he found me way too morose and I found him way too touchy, lazy and entitled. So I liked the change in air, but it was clear something was up. One day Jim let me in on it. He looked one way, then the other, and then confided that the M.E. was engaged in some “really heavy shit” and it involved our mild, blinking editor-in-chief. Jim swore me to secrecy and I kept my promise to stay quiet.

Then came the coup. It was announced by a memo from headquarters: The editor-in-chief was out and the managing editor was taking his place. Not only that but now he would be publisher as well. The change was dazzling; Jim walked on air. Pay raises and promotions were handed around. Oddly, the assistant managing editor was kept on and given a lot more money. The copy chief left, and after some agonized vacillation I said yes to replacing him.

Meanwhile, Jim had his slice too. Our paper had a weekly version that cannibalized articles and photos from the daily. It had limped along for years, never able to find a market. “That one's a goner,” our copy chief had said to me, shaking his head, after he attended a meeting of executives. But the top boss decreed that preparing this edition would now be Jim's only responsibility. Jim received a nice title and raise to go with it, and he officially left behind his duties at the copy desk. “This is going to put me up with the big boys,” he told me.

Three weeks later his job was gone. Just as the departed copy chief predicted, the company decided to pull the plug on our weekly edition. Given that our new boss, the former managing editor, was a smart man and a star at office politics, I have no idea why he left Jim out on a limb. Maybe he couldn't stand to see his boy without a gift and he thought the weeks wouldn't pass and the reckoning wouldn't come. The boss was clever, but he wasn't a man of strong character.

With the job gone, Jim had no place to go but back to the copy desk. But he had already said the work was beneath him, and during his three weeks of glory he had been quite rude when I asked him to pitch in on deadline. And, of course, I had spent months watching him backbite the previous copy chief. When Jim told me his new situation, I didn't know what to say except that I had to think it over. An hour or so later he told me to forget it, the request was rescinded, he and his wife were moving to her hometown and her parents' place.

Why didn't our boss order me to take Jim back? Because I worked hard and did a good job, and he needed me. There weren't that many competent people on staff; it's often like that in places where pal-ship dominates. So Jim left. Well, that's life at the summit of power. The big play goes down, and suddenly you're out when you thought you were in. I don't know what he and the boss said during their last interview, but I do know that Jim still adored him. It was evident in his word and manner to the final day. He'd been hung out to dry, but his love went beyond self-interest.

I did okay. I mean, the job was miserable because of the workload and my co-workers' tantrums and so on, but I was a boss and making money that I never thought I'd make. Now and then I told myself I was the quiet, shrewd, watchful man who rose while others discounted him, like Claudius in I, Claudius. I also figured I might be like Michael Corleone in The Godfather. He didn't say much and he kept his face a mask. I was unable to say much and my face couldn't move because of my shyness—so, hey, close enough. As indicated above, my success really came down to this: I kept my head down and I worked. I think I was also much smarter than most of the people on staff, but an office politician likes to think of himself as smart and also tough. In my case that second point is where delusion entered.

Yet all of us were deluded. Jim was a chump, and his beloved boss was a chump for giving him a gift that had to be repossessed. The last editor-in-chief, the man who got toppled, was a chump for trusting the man who toppled him. Mr. Steel Teeth had hired his nemesis out of college and promoted him up the ranks from reporter. After making him managing editor, he sat with him for private one-on-ones about the paper every morning. I guess the impending coup never got mentioned.

Here's another chump: the assistant managing editor. A year after the coup, the editor-in-chief figured his team was finally steady enough to make her dispensable. She was fired for general and prolonged obnoxiousness. And a year after that, the editor-in-chief was fired. He and the company's president, the man who had made him our combined publisher and editor-in-chief, had been having their differences. The editor-in-chief and publisher, using a tactic that worked quite well at the newsroom level, had responded by signaling to his boys that they could be rude to the president. Soon the editor-in-chief and publisher was no more. The president had his ex-boy's letter of resignation on his desk.

To give them credit, the team stayed loyal to its fallen boss. They stood on their desks as he strode out of the office (Dead Poet's Society), and over the next few months they ditched the paper and found jobs elsewhere. I stayed on and kept my salary. As explanation, I told a colleague about that fine poem “The Vicar of Bray” (“Come what will and come what may, sir/I will be Vicar of Bray, sir”). But really, I was just scared of job interviews and surviving a new office full of people. I had my shelf now and I stuck to it like a limpet.

Staying at the paper, I kept up in a vague way with the career of the exiled editor-publisher. He wrote a newsletter about our little field for a big-name entrepreneur in financial reporting. The newsletter didn't drum up sufficient demand and was killed. After that he moved to the top financial wire service, where he became a reporter still covering the same field. After 9-11 I saw his name in Time, but in very small print. There it was in the credit line for a graphic showing (I think) the floor plan of the World Trade Center as it used to be. I don't know how his name got there, but that was the last time I ever saw it. As far as I know, he never ran another publication or anything else.

I suppose a Caro character (sorry, a Caro historical subject) would have clawed his way to mastery of the wire service, or of some damn thing, because of sheer, indomitable, unbending, limitless will to power. Maybe my fallen boss had just some will to power, not the full load, and the full load is what you need before you get someplace interesting. Caro would probably say as much, given the space he devotes to the subject in his books. Absent that, you don't wind up in the name of a building or on the front page of the papers or in the dense index to a massive book, or even in the boardroom of a leading purveyor of news to busy financial professionals. You're just someone who lied when he should have told the truth, and who thought that this meant he was doing something big. Looking back, that last bit is what strikes me. We thought we were doing something big when we were just folding ourselves small.

What about my slobby ex-seatmate? Ten years back I did some Googling and found he was news editor for the paper in his wife's old hometown. News editor is where papers stick someone who's been on staff a while but hasn't proved especially useful. I checked again recently and his name was gone.