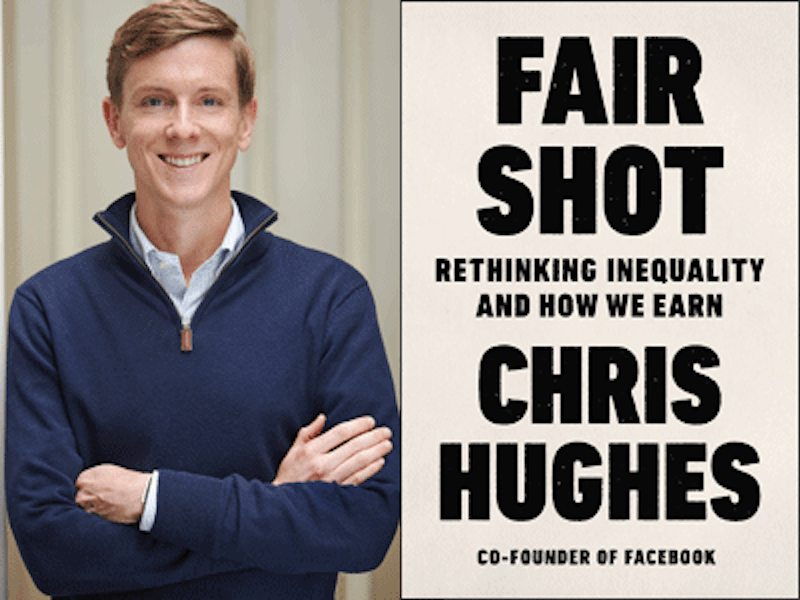

A refreshing aspect of Chris Hughes’ memoir/policy proposal, Fair Shot, is that an immensely wealthy guy’s admitting that much of his $500 million fortune’s attributable to serendipity. Perhaps his 2012 purchase of The New Republic, and the ensuing disaster, helped him reach this humbling conclusion, and that was the best mistake he ever made. Making half a billion dollars for three years work before you hit 30 can scramble your mind so badly that you might even think you're going to make a publication like TNR get to the break-even point.

Hughes drawing Mark Zuckerberg as a sophomore year roommate at Harvard was like winning the Powerball lottery. The author's candid acknowledgement of his good luck is at the heart of the policy argument he wrote this book to make—that all the unlucky Americans making under $50,000 (including students) are entitled to a guaranteed income of $500 per month, funded by a tax increase on the top one percent.

Hughes is a wealthy idealist who realizes he's been rewarded disproportionately for this efforts and contributions to society (he got rich “selling” a product people aren't even willing to pay for) and understands that those doing the indispensable work aren't normally able to tap into the global economy. He recognizes that wealth disparity is a cancer to the nation. The top 1/10th percent of the population’s wealth now equals that of the bottom 90 percent. Today's winner-take-all economy, says the author, is great for the Amazons, the Googles, and the Facebooks, but it's “pulling the rug out from under the middle class and lower-income Americans” who are now faced with the prospect of having to compete with artificial intelligence and robots.

Hughes’ funding proposal for his cash-payout program is a 50 percent tax rate on income and capital gains for Americans earning more than $250,000. His travels in Kenya, where he became involved with a non-profit called GiveDirectly, taught him some lessons on bootstrapping people with cash. Hughes observed that cash transfers with no strings attached, as opposed to “bowls of rice” or other aid interventions, were the most effective means of improving lives. Cash allows villagers to make autonomous decisions—they can pool their money to build a well, improve their homes, or both. The author cites statistics from MIT’s Poverty Action Lab to support his first-hand observations that cash makes people happier, less stressed, and more satisfied with life.

Hughes’ guaranteed income plan, which he claims will lift 20 million people out of poverty, differs from the more commonly discussed concept of universal basic income (UBI), in that it doesn't provide enough to live on, meaning that it wouldn't act as a disincentive to work. It merely provides what he calls “a floor below which people could not fall.”

The author lavishly supports his assertion that no-strings cash is the best way to reduce poverty and improve the lives of those unable to reap the massive rewards of the modern economy. Even if AI, automation, and robots don't end up stealing a lot of jobs, the price of housing, healthcare, and energy won't stop rising, while the bottom half’s incomes have remained stagnant for decades—they’re getting squeezed more every year.

It's obvious, however, that Hughes has spent much less time researching the funding side. He mentions the possibility of financing his plan with a carbon emissions tax, and the Bernie Sanders idea of taxing individual transactions on Wall St., but he's set on a tax boost on “people like me who have benefited massively from the new economic forces,” although he doesn't back up his choice with much more than vague talk of “fairness.”

The Facebook co-founder sensibly suggests adjusting the tax code so investors have to pay the same tax rate as workers on their wages, and closing tax loopholes such as on inherited assets, but still leaves readers wondering why he chose the top one percent to foot the bill. Why not the top half of that group, or the top quarter? His choice seems arbitrary and overly reliant on the “one percenter” trope.

Hughes spends just a fraction of his 188-page book on how to pay for his idea. He’s leaving that to others. The author and his husband, Sean Eldridge, have made a commitment to give away all their money over the course of their lifetimes. Hughes is a generous guy who cares about helping people who’s now counting on other people with some money to be as magnanimous as he is. But the catch is that the family making $300,000 with four kids going to college will get hit much harder than he will with a 50 percent tax rate. A flaw in his reasoning is lumping a high flyer like himself into the same economic category as those at the bottom of the one percent.

This isn't to say that Fair Shot isn't a worthy effort in an important field of study. There's no consensus on what the ideal guaranteed income plan should look like in practice. Chris Hughes is putting one version forth. He's advanced a debate that's just starting to pick up steam. Other versions of guaranteed income plans are now being tested in places like Ontario, rural Kenya, and Glasgow. When their results register, they'll be added to the mix. The benefit of just giving away money to people isn't all that intuitive, but Hughes makes compelling arguments in its favor. For ideas on how to get it done politically, people will need to turn to someone else. The concept of “free money” is a hard sell.