On one Monday night in college a friend called to tell me that he was holding a Martin Luther King Jr. Day party. The centerpiece of this was people drinking 40s of Old English, eating fried chicken, and playing N.W.A. He wasn’t from a fraternity, but a corduroyed hipster from a local indie pop band. This wasn’t the South; it was Eugene, Oregon. It wasn’t the early-1980s, it was 2006.

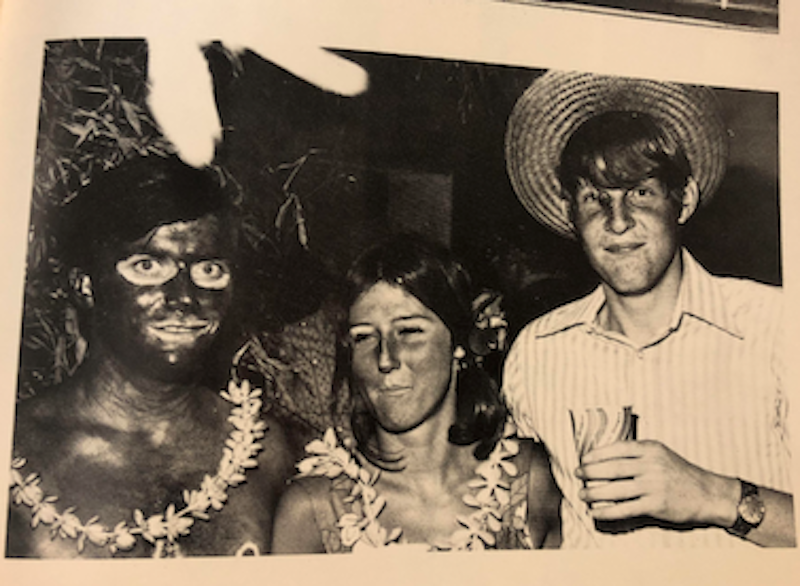

The recent series Virginia controversies, bookended by Gov. Ralph Northam and Attorney General Mark Herring both admitting to appearing in blackface during college, has inspired a slew of articles about change. This suggests that blackface, one of the most dehumanizing caricatures of black people imaginable, was perhaps just a tasteless joke in its time. Today our pasts are more easily accessible than ever, so the pundits are correct that a reckoning is taking place that they were completely unprepared for.

While anyone applying for competitive jobs online scrubs their social media accounts, it doesn’t take long to find artifacts that people would rather keep buried. I was in college when Facebook skyrocketed, and because it placed no limit on photo uploads you often see massive albums for individual parties, captured at all angles. Search for any holiday or theme party and you’ll find a slew of racist caricatures, from pale-painted Geisha costumes to wide-brimmed sombreros to full headdresses on white lacrosse players. It took me 10 minutes to find a white student slathered in brown paint.

There will be a lot to account for as time passes, especially for those of us whose youth is easily accessible on social media backlogs. But how does this reality apply to something as blatant as a rich white student painting his face and posing next to a Halloween Klansman?

Blackface comes out of an American tradition of mocking slaves in theater across the country starting in the 1830s; through Reconstruction and into Jim Crow it continued as a brutal spectacle. The function was to exaggerate supposedly African features, apply significant stereotypes about intelligence and sexuality, and turn them into the basest of activities. Whites know themselves in apartheid by their shared revulsion at races they have ascribed “otherness” to, and blackface allows them to purposefully rob black people of all human dignity and to find joy in that cruelty. It has its own metapolitical function: while blackface makes few political claims outright, it helps reinforce the lingering racial supremacy in the heart of Americana, encouraging the impulse that black people have to be controlled, forced into subservience, and made victims of violence for society’s good.

While the claim that “times have changed” persists as a defense, it was widely known as offensive by the time they slathered up their faces, and that’s why they did it. These were intentionally offensive costumes, funny to them because they were transgressive, and, in doing so, they were able to appeal to something that was hidden yet never eradicated. They signaled to each other in the same way that the most extreme racist jokes, told in whispers in parties of insiders, still create explosive laughter. They may have walked the public lines of “racial progress,” but in private they enjoy succumbing to racist narratives.

I was born in 1984 and throughout the 1990s and into the 2000s it was common to hear racist jokes told in public venues, not because we were monoracial communities, but because white kids assumed the consequences of those jokes were gone. In perfect episodes of white blindness, the racist joke was an attempt to say that society was essentially post-racial, and therefore the “sensitivities” of anti-racism were puritanical and unnecessary. The racist joke then serves as a safety valve for the tension: white people can absolve themselves of responsibility by making a claim that white supremacy has been sufficiently unseated.

The reality is not that these rich, white politicians have a blackface problem, but that white supremacy makes itself known in shocking ways that were just as prevalent today as they were then. Heightened technology, cell phone cameras, social media, and the like have made this easily confrontable, yet most journalism seems lost in its ability to recognize it. The blackface is one we have all known, from Greek Row to YouTube comedians, and therefore it elicits so much fear.

On Halloween of 2013 I was resigned to a quiet night at home—my partner was stuck at work—so I loaded up on candy. We lived in a busy suburb of Portland, Oregon, and since I was still reeling from some recent family tragedies I’d been looking forward to some of the normalcy that comes from trick-or-treaters. Towards the end of my night a young couple came with their son who was dressed in a nice three-piece suit, a small lapel pin I had trouble making out in the dark, and a face that was almost blinding in its jet-black shade. I stood there stunned since, in the moment, I was having trouble putting together exactly what his costume was. His proud mom started humming “Hail to the Chief.”

It wasn’t until the blackfaced caricature of Barack Obama left my driveway that I got what his parents had dressed him up to be. There wasn’t a hint of guilt in their eyes, and they either didn’t know or didn’t care about what they’d set their son up for.

The Virginia scandals will fade from the news cycle, but only because they’ll be replaced by another similar story. And another. Because this is the story not just of white supremacy in America, but also of white people in general. It takes much more than personal accountability and retribution to uproot something fundamental to U.S. society. And that only starts when we know that culpability is all around us.