The first time I heard a Lou Reed song I was 18 and floating down the Chattahoochee River in a canoe. A shirtless Georgia teenager stood on the riverbank slapping his paddle at some swimming kids as a boombox blasted “Walk On the Wild Side.” At one point the teen’s paddle made contact with a young boy’s skull. I heard a loud “thwap” and the boy fell face first into the water. The teenager laughed maniacally as the boy’s friends pulled him to safety.

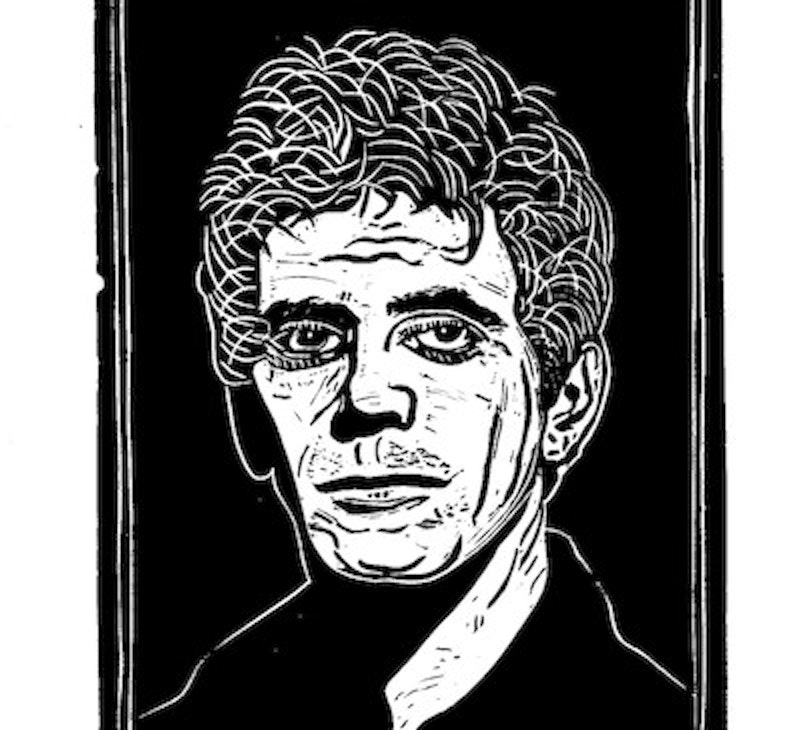

This is how Reed’s music entered my life. There was something magnetic about the sound, the raw and minimal guitar riffs, and the risqué lyrics. Most pop music was safe. Reed was dangerous. The music had a dark energy, an urgent power with distorted guitars and atonal vocals.

The first Reed album I bought was Transformer (1972). From the moment he sang the words “Vicious, you hit me with a flower” I realized there was something deeper going on, ironic storytelling in a way I’d never heard. On “Perfect Day” Reed sings, “You made me forget myself, I thought I was someone else, someone good.” The line perfectly encapsulated my teenage angst, self-doubt and dim hopes for future redemption. Reed repeats the frightening refrain, “You’re going to reap just what you sow.” The words penetrated my soul like a warning, a call to pay attention to my own words and deeds.

When I discovered the Velvet Underground, I was spellbound. The music was real and edgy as if made in someone’s garage. The guitars were droning and slightly out of tune, the drums scratchy and dirty. The sound had a grit and authenticity. This was my first experience of lo-fi music and Reed was my first rock star crush.

He was a rock ‘n’ roll bad boy. He abused drugs and alcohol, trashed hotel rooms, cursed at reporters and engaged in bar brawls. But Reed was different. Where most rockers had affairs with supermodels, Reed opted for trysts with transvestites. Where typical pop stars sang about how much they missed old girlfriends, Reed sang about bondage and sadomasochism (“Venus In Furs”).

Google the words “Lou Reed was an asshole” and you’ll find dozens of incidents describing his brutal, selfish, misanthropic behavior. There was the time he slapped David Bowie after Bowie suggested Reed cut back on his drug and alcohol use. Or the time he called Bob Dylan a “pretentious kike.” (Reed himself was Jewish.) His Velvet Underground band mate John Cale called Reed a “twisted, scary monster.” Paul Morrissey, manager of the Velvets said Reed was possibly “the worst person who ever lived.”

Friends and admirers grew familiar with Reed’s moody tantrums and profanity-laced assaults. At the Manhattan clothing store RRL a sales clerk told Reed he was a big fan. Reed responded, “I don’t know what the fuck you’re talking about. Fuck off.” Howard Sounes, author of Notes From the Velvet Underground: The Life of Lou Reed, writes that Reed “was constantly at war with family, friends, lovers, band members, managers and record companies.” Reed described himself as a “fucking, faggot junkie.”

As a person, Lou Reed was clearly complicated. As an artist, he inarguably shaped the musical landscape. He was an authentic rock ‘n’ roll rude boy. Without him there would be no punk rock. (Sid Vicious took his name from the Reed song “Vicious.”) There would also be no Grunge or Shoegazer scenes. Brian Eno claimed, “Everyone who bought the first Velvet Underground album started a band.” Reed’s songs directly informed the musical style of Joy Division, Jesus & Mary Chain, Galaxie 500, Dream Syndicate, Luna, Spacemen 3, the Dandy Warhols, the Feelies and the Pixies.

In the brilliant but dark album Berlin, Reed told the story of Jim & Caroline, a troubled couple whose relationship crumbles as they fall into drug use, prostitution, domestic violence and ultimately suicide. This is the heady stuff of literature, not the trivial fare typically found in rock music.

Reed’s heroes were literary figures like Hubert Selby Jr., Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg. During his days as a student at Syracuse University, Reed started a literary journal called The Lonely Woman Review. He wrote short stories and read poems aloud at St. Mark’s Church along with the Patti Smith and Jim Carroll. Reed studied creative writing with the poet Delmore Schwartz, whom Reed credited for teaching him how to “use the simplest language imaginable” to create the heaviest impact. (Schwartz was the inspiration for Saul Bellow’s novel Humboldt’s Gift.) Under Schwartz’s tutelage Reed wrote poems that became the songs “Heroin” and “Sister Ray.”

One of Reed’s favorite books was the 1963 John Rechy novel City of Night. The book was a landmark of queer literature chronicling a gay street hustler’s travels through America. Reed channeled this energy into his own songs about street life such as “Waiting For the Man.”

Reed yearned to write a novel and put it to music. In a 1991 interview with author Neil Gaiman, Reed explained how he used prose techniques in songwriting. “There are certain kinds of songs you write that are just fun songs, the lyric can’t survive without the music. But for most of what I do, the idea behind it was to try and bring a novelist’s eye to it, to try and have that lyric there so somebody who enjoys being engaged on that level can have that and have the rock ‘n’ roll too.”

Reed grew up in a middle-class Jewish family in Brooklyn. When he was nine, they moved to Long Island. His mother had been a teenage beauty queen while his father abandoned dreams of becoming an author and wound up as a tax accountant. At a young age, Reed experienced social anxiety, panic attacks and depression. He spoke of being beat up routinely after school. He escaped into music, mimicking guitar sounds he heard on the radio.

He began experimenting with drugs and formed a high school doo-wop band called The Jades. The band played gigs in shopping malls and dingy bars. His parents were overprotective of their son, especially after learning of his drug use. They fought often but Reed rebelled. In one instance, an inebriated Reed crashed the family car into a tollbooth on the parkway.

Reed waited tables at a local gay bar and began having sexual encounters with men. He tried heroin for the first time and contracted hepatitis. He decided to attend New York University; during freshman year, he had a mental breakdown. His parents drove to the city, brought their son back home, and sought professional help. Psychologists suggested Reed might have schizophrenia. He was briefly admitted to a psychiatric institution where he confessed to “homosexual urges.” Doctors recommended electroshock therapy. Reed’s parents consented and he endured more than two-dozen ECT sessions. The treatments wreaked havoc on his short-term memory. Reed never forgave his father, something he wrote about in the 1974 song “Kill Your Sons.”

Reed recovered and enrolled at Syracuse University. After college, he moved to New York City and befriended the Welsh musician John Cale. The two became roommates in a Lower East Side apartment and busked on Harlem street corners, Reed on guitar, Cale on viola. They formed a band initially called the Warlocks, then the Falling Spikes before settling on the Velvet Underground (taken from a book about a 1960s secret sex subculture).

In 1965, they met Andy Warhol while playing a gig at the Café Bizarre in Greenwich Village. Warhol became the band’s manager and the Velvets recorded four studio albums. The albums sold poorly but the music is now considered among the most innovative of the period. Reed grew frustrated and the band disintegrated. He had another breakdown and moved back into his parent’s home. He took a job at his father’s tax firm as a typist for $40 a week. In 1971, he signed a contract with RCA to be a solo artist. His career was back on track.

For Reed, the 1970s was a decade of substance abuse and excess. He told a friend he “was going to take meth every day for the rest of his life.” He binged on scotch and, according to his first wife Bettye Kronstad, he became “a violent drunk on tour.” He hung out with drag queens and became romantically involved with a transgender woman named Rachel.

As the punk scene exploded in the late-70s, Reed became a fixture at CBGB, watching the bands he helped inspire. He was generally dismissive of punk though he loved the Ramones. Reed’s reputation for misbehavior and surliness became legendary. During a 1975 tour through Italy, he pulled a knife on his violin player and told Italian reporters he came to Rome to have sex with the Pope.

It wasn’t until the late-1990s that Reed finally found a semblance of happiness. He took up meditation and practiced tai chi two hours a day. After two failed marriages, he began dating the musician and performance artist Laurie Anderson. The two made several recordings together and were married in 2008.

Reed’s year of hard drinking and drug use led to hepatitis and liver disease. He developed liver cancer and underwent a liver transplant in May 2013. After the surgery he posted on his website of feeling “bigger and stronger than ever.” In October 2013 he died of the disease.

Laurie Anderson wrote that Reed was a “prince and fighter” and that his last days were peaceful. She did her best to debunk Reed’s dark reputation saying, “I never saw the blackness.” After his passing, the rock community paid tribute. Bono said, “Every song we’ve ever written was a rip-off of a Lou Reed song.” David Bowie: “He was a master.” John Cale wrote, “I’ve lost my schoolyard buddy.” Reed’s last tweet posted hours before his death read simply: “The Door.”