Watching the movie Hud last week made me think about the use of music in films. The entire soundtrack, a sparse instrumental composed by Elmer Bernstein, lasts only six minutes. Quentin Tarantino would set pre-existing pop songs to that script—the "needle drop" technique—and I'd be curious to see the result. But he'd produce a different movie altogether from the original because there's an alchemy between film and music that makes a scene set to a song as irreplicable as a snowflake.

Just as a song affects a movie, a movie can affect your relationship to a song you were already familiar with. Directors shouldn’t be too obvious with song selection. They shouldn’t leech off of the song's power, but rather recontextualize it and give it new life. A pop song in a movie should deliver an element of surprise. Nobody needs to hear "White Rabbit" or "Bad to the Bone" in another movie ever again. A needle drop can tell you something extra about a scene or a character, but it shouldn't be used as a cheap shortcut to the viewers' emotions that the film can't supply—that's lazy and manipulative.

Here are some top examples of skillful needle drops:

"Fight the Power," by Public Enemy, Do the Right Thing—This song plays as Rosie Perez pops some aggressive, seductive dance moves in Brooklyn's Bed-Stuy neighborhood in one of best opening credits sequences and then continues playing inside the pizza joint where a group of black men are confronting the owner, Sal, because no photos of black people are on his Wall of Fame. Some films build slowly towards an emotional crescendo at the end; this one begins with a crescendo that's propelled forward by the song's insistent beat and defiant spirit.

"Layla," Derek and the Dominos, Goodfellas—Scorsese used just the outro portion of Eric Clapton's best song to create cinema that has a music video feel to it, as if the musical choice came first and the director fit his footage into it. Just as this lovely, forlorn coda is a meandering wind down after a searing song of forbidden love, it's also a coda to the action in the film. The big robbery has taken place, and then Jimmy (Robert DeNiro) got busy killing almost everyone connected to it. The instrumental plays over a montage of carnage, and rarely has the aftermath of violence been rendered with so much aesthetic grace. It's hard to remember that scene and not hear those mournful piano chords, and vice versa.

"In Dreams," by Roy Orbison, Blue Velvet—David Lynch chose a song about dreams for his film of an extended nightmare. Psychopath Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper) is obsessed with the tragic song about obsessive, unrequited love that can only be attained in dreams. There's an element of surprise here, given his animalistic nature. Frank spends much of his time in a manic state terrorizing people, but when his weird friend Ben (Dean Stockwell) lip syncs this operatic torch song at a gathering at his residence, Frank's mesmerized into a catatonic state, moving his lips to the lyrics. Frank forces himself out of his trance so he can get on with his mayhem, but not before producing an unexpected moment of sweetness and vulnerability within a disturbing movie.

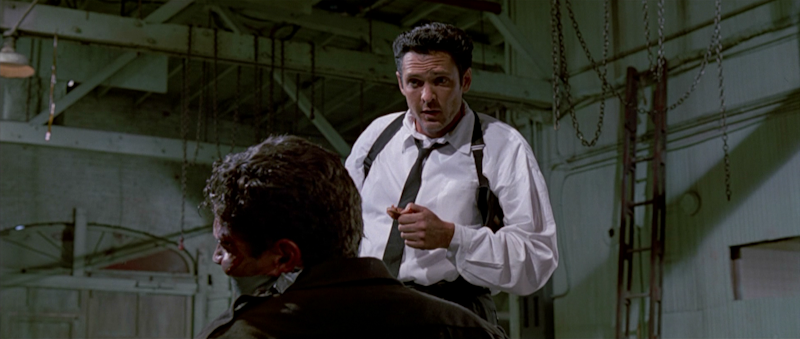

"Stuck in the Middle with You," Stealers Wheel, Reservoir Dogs—Quentin Tarantino uses pop music memorably, but this bouncy selection stands out. He chose it as an ironic counterpoint to grisly violence, thus amplifying the savagery by contrast. If a brutal song were used, then the action must compete with the music and its power may be diminished.

Ironic song choices eventually became a cliché, but in 1992 it was fresh. The director's needle drop does some storytelling here. Tarantino has Mr. Blonde (Michael Madsen) dancing to the pop music he's put on the radio while preparing to cut a cop's ear off to highlight the fact he, like Frank Booth, is a psychopath. Gerry Rafferty sings—“I don’t know why I came here tonight/I got the feeling that something ain’t right”—and it's like he's reading the cop's mind. For this scene, Tarantino's most controversial because of the ear amputation, the director picked the music first and choreographed the action into it.

"I've Got You Babe," Sonny and Cher, Groundhog Day—This is another example of how a crummy song can work perfectly in a film. Phil (Bill Murray) is stuck in a time warp and must relive the same day over and over. Every morning he wakes up at six o'clock to the same lame song, an instant reminder that he's not moving forward in time. Phil comes to hate hearing the song so much because he knows what it signals, but even when he smashes his clock radio it's intact again next morning and the cycle begins once more. The song is played so much that it becomes a character of its own with an indispensable role in the film.

"Dropped In (To See What Condition My Condition Was In),” The First Edition, The Big Lebowski—This song, the centerpiece of a wide-ranging Coen Brothers soundtrack, is used during an elaborate bowling-themed dream sequence featuring Jeff "The Dude" Lebowski (Jeff Bridges), who'd just been slipped a Mickey. The tune’s cheesy psychedelia accentuates the freakiness of the dream, which features Bridges doing some hilarious dancing while dressed as a porn movie cable guy and Julianne Moore clad in a Viking outfit. The directors took an old, forgotten song and repurposed it.

“Imagine," John Lennon, in The Killing Fields.—This song is sappy, but it helps make Roland Joffé film's ending one of the most poignant in cinematic history. New York Times reporter Sydney Schanberg (Sam Waterston) is reunited with his Cambodian interpreter Dith Pran (Haing S. Ngor) after Pran had escaped after being captured by the Khmer Rouge. The song's dreamy message of longing for a better world gives the movie's conclusion an emotional wallop, but it only works if you watch the film in its entirety so you can understand the ordeal Pran had endured.