Films built to win Academy Awards have been around since at least the 1940s, but it took until the late-1970s for Oscar nominations to become a planned part of a movie’s PR campaign. Ordinary People, released in September of 1980, came out too early in the year to be true Oscar bait, but that’s the sort of film it is: studied and tasteful realism, studied and tasteful acting, studied and tasteful cinematography, studied and tasteful directing and dialogue and everything.

The film eventually won four Oscars, including Best Picture. Robert Redford won Best Director, and screenwriter Alvin Sargent won Best Adapted Screenplay for his take on Judith Guest’s 1976 novel. But Oscar wins do not necessarily indicate a movie of lasting interest. The Criterion Channel recently included it in their selection of films about psychiatry, which is as good a reason as any to consider how well it holds up.

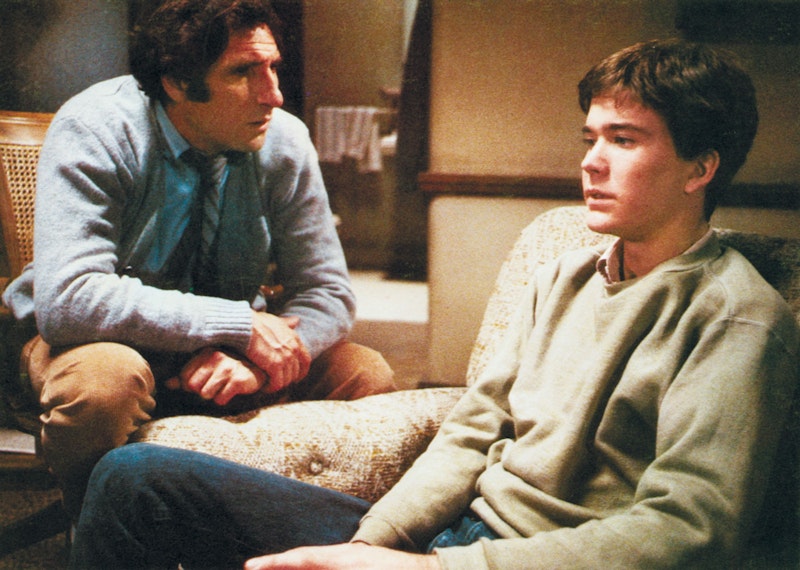

The story follows an upper-middle-class family in the suburbs of Chicago. Calvin Jarrett (Donald Sutherland) and his wife Beth (Mary Tyler Moore) are worried about their son Conrad (Timothy Hutton, who took the film’s fourth Oscar as Best Supporting Actor) following the recent death of his older brother Buck. They send him to see a psychiatrist, Dr. Berger (Judd Hirsch), but Beth still has tensions of her own around Buck’s death, and her relationship with Calvin is suffering due to her habit of suppressing troublesome emotions.

The story follows from this situation through a series of scenes as the characters bounce off of each other, sometimes helping but often causing each other pain. Conrad’s slow recovery of mental health is roughly paralleled by the disintegration of his parents’ relationship. There’s a subplot with a girl Conrad met during his stay in a mental hospital, and another revolving around his relationship with a classmate.

There’s nothing surprising in the development of the story, or in the dialogue or writing. It’s notably weak at times, particularly when Berger’s made to say the sort of thing that passes for wisdom in Hollywood melodrama. “A little advice about feeling, kiddo,” he tells a despondent Conrad, “don’t expect it always to tickle.” Hirsch does the best he can, but there’s a limit to how well material this trite can play.

On the other hand, the actors consistently elevate what they’re given. I’d guess they were the main reason the film won an award for its script—good acting can not only make pedestrian dialogue sparkle, but also illuminate character arcs that are uninteresting on the page. Redford pulls career-best performances or close out of all the main cast. And since one member of that cast is Donald Sutherland that’s saying something.

Redford’s acting background likely helped, and also likely helped his decisions about what to show: when to underline emotion with a close-up, or when to emphasize the connection between characters with a two-shot. The movie’s visuals are always anchored by the characters and their emotions; this isn’t a movie about landscape or about complex tracking shots. Sets are decorated unobtrusively. Lighting is textured and expressive, but never obviously spectacular.

Which is to say again that the look of the movie is studied and tasteful. Thematically, though, the film’s not as sophisticated. The novel used its title with some irony: the Jarrett family’s returning to being “ordinary” after the immediate aftermath of Buck’s death. That irony’s lost in putting the novel on the screen, and without context the film seems to be making a statement about what kind of people get to be ordinary—well-off straight white suburbanites. Even if you assume the point’s that the Jarretts are unhappy despite being “ordinary,” the movie rarely has the self-awareness to put them in a wider social context and so question what “ordinary” means.

There is some of that with Berger, as Beth observes he has a Jewish name. And there are hints of a class consciousness, with Beth’s family rich and Calvin from a less privileged background. But then there’s no evident awareness of non-straight sexuality, which is notable since Conrad’s on the high school swim team; every so often the screen’s filled with well-built young men clad only in swim trunks, and no subtext is ever apparent. The movie prefers ordinariness to complexity, interested in a kind of character-based realism but uninterested in exploring the assumptions of the society that shaped the characters and through which they move.

So Beth’s discomfort with Berger’s ethnicity is vestigial, merely another sign that Beth’s the real antagonist of the film. Berger’s role in the story is to be the voice of external wisdom who heals Conrad. He’s useful to the extent he fits into that story structure, but never presents any kind of complex psychiatric idea.

Hirsch does a capable job of playing to the image of a kindly doctor. Classic Hollywood viewed psychiatrists as oracular figures of wisdom; here, a few decades on, the psychiatrist is still the healer but not because of any special education or knowledge. Conventional wisdom and a warm affect are enough. Those characteristics are useful for a therapist, but the film’s attempt to represent psychiatric healing remains too glib.

Studied and tasteful: Ordinary People never becomes more than that, though it never becomes much worse. The drama’s clunky because the characters are a bit too facile and the filmmakers’ understanding of their society is much too underdeveloped. It’s not as boring as it should be, due to outstanding performances. But it’s too safe, too earnest: too much a piece of Oscar bait, if a successful one.