What a treat it was for me in the 1960s, when my parents and I would board an express train from Bay Ridge to Manhattan. On our weekly bus rides to one Brooklyn outpost or the other, I’d carry my pencil, flashlight bulb and plastic Carvel spoon, the better to imitate the lampposts I saw going by out the window.

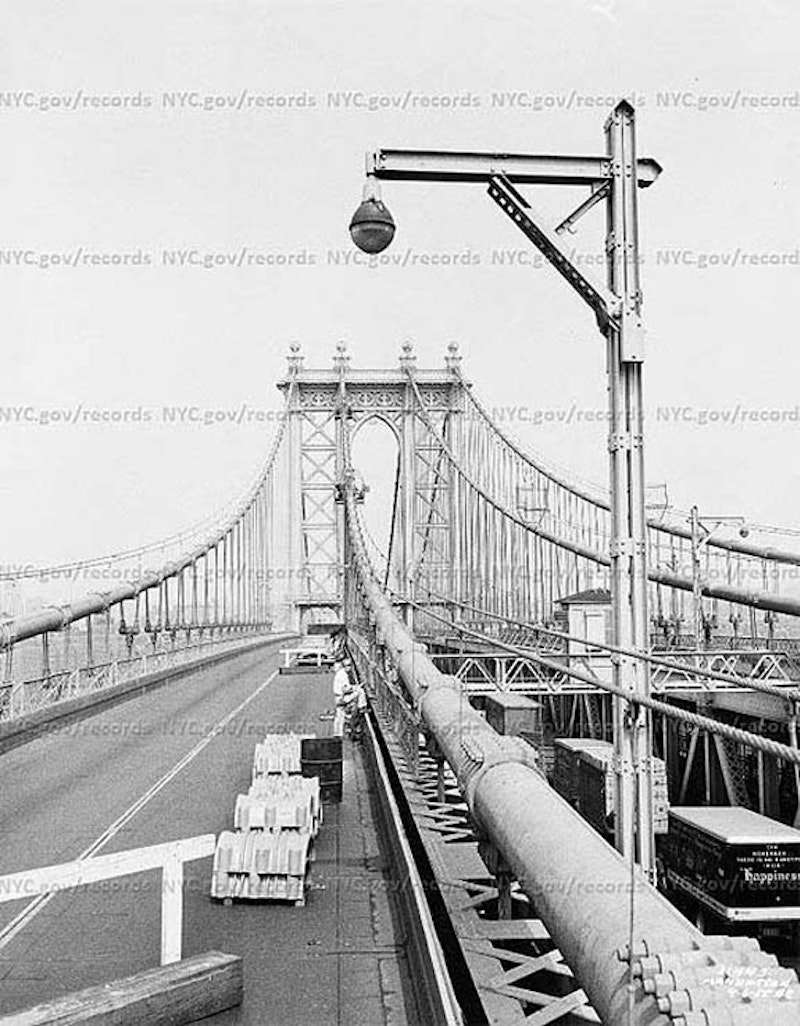

When riding the N train into Manhattan it emerged into the light to traverse the Manhattan Bridge, and in the early days, I’d see these very utilitarian and mechanical-looking lamps arrayed on the roadways, which are on either side of the bridge over the tracks, with a third roadway in the center. This photo is from the New York City Municipal Archives, taken in 1955 and I recall truncated versions of these lamps in the early-1960s before they were replaced with cylindrical lamps with short masts carrying Westinghouse AK-10 “cuplights.” Even those were interesting, though. To get around the suspension cables at intervals, they had to be made to bend mid-shaft, producing an interesting shape. By the 1980s, they’d been replaced by straighter versions.

For decade after decade the Manhattan Bridge pedestrian walkways, on either side of the bridge outside the subway tracks, were not only out of commission but completely absent: the ribs of the superstructure were there but there was no walkway: you’d look out the train window and see the East River where the walkway would be.

In 1995, when the city finally completed about a decade of subway repair on the bridge, though, they deigned to rebuild the pedestrian walkways on both sides. At the same time, high fences were built along the railings to prevent anyone from leaping into the drink or throwing objects on ships passing beneath. The north “walkway” was designated for bicycles, with the south walkway for regular pedestrians, though it doesn’t really work that way.

There’s an iron superstructure that covers the middle roadway for a distance on the Manhattan side. While it’s purposeless now, it was constructed in the early-1960s as part of the city’s effort (spearheaded by Robert Moses) to build Interstate 478 across the bridge, then north along Chrystie St., west along Broome and then connecting with the Holland Tunnel to New Jersey. After years of lawsuits and opposition to the building of what was dubbed “LoMex,” the Lower Manhattan Expressway, the expressway was finally cancelled in 1969. The LoMex would’ve connected to both the Manhattan and Williamsburg Bridges.

Though the plan was scotched, bumper-to-bumper traffic across Manhattan between the East River bridges and the Holland Tunnel hasn’t been addressed, and Canal St. remains a horn-honking, exhaust-fume-belching slice of hell. Someday, a new Moses figure will revisit the idea and build an underground tunnel connecting the East and Hudson River crossings.

The Manhattan Bridge was built as architecture was beginning to move past Beaux-Arts into more utilitarian modes. But the bridge still has several intriguing decorative elements that can be seen at the two towers (which are supported by two columns apiece). A large plaque listing the bridge builders and NYC officials during construction can be found on the Manhattan tower on the north walkway. The Manhattan Bridge employs 21-inch steel cable, the strongest of all East River bridges. Original plans called for it to be a parallel wire suspension cable bridge, then an eyebar/chain bridge before returning to the original plan.

The twin roadways on either side of the bridge atop the subway lines were originally used by trolley lines. Trolley service over the bridge ceased in 1929, and the lanes were then taken over by cars.

Subway service on the Manhattan Bridge began in 1915. Originally the Sea Beach Line (today’s N) traversed the bridge on the north set of tracks, with the south side connecting the BMT 4th Ave. line with the Chambers St. station on the Nassau St. line.

In 1967 the track connections over the bridge at both ends were drastically rearranged and altered. As a result, the little-used connection with the Nassau St. line was severed, with the Sea Beach taking over the south end of the bridge and the Brighton Line gaining a new connection to Manhattan. In the 1980s and 1990s, the wages of both placing the subway tracks on the outside edges of the bridge’s undersides resulted in the discovery of major damage to bridge supports. Subway cars, as they cross the bridge, cause the structure to twist slightly, with dire results as the decades passed. The fact that the tracks on the northern end got much more use than those on the south end was also a factor in the torsion. To repair the bridge it was necessary to shut down subway service on the south tracks, then the north, for most of the 1990s. Service was not restored to full capacity until 2004.

As this somewhat obscurely placed sign at the Jay St. entrance to the south pedestrian walkway indicates, bikes are legally enjoined from traversing it: they’re only legally able to use the north walkway. However, with no real enforcement of the dictum, bicycle riders are beginning to take over the walkway that is legally meant for pedestrians only. Since the NYPD has other fish to fry, the Manhattan Bridge may ultimately get as bad as the share pedestrian-bicycle path on the Brooklyn Bridge.

—Kevin Walsh is the webmaster of the award-winning website Forgotten NY, and the author of the books Forgotten New York (HarperCollins, 2006) and also, with the Greater Astoria Historical Society, Forgotten Queens (Arcadia, 2013)