I’m reading Free Fall by William Golding again. It’s one of Golding's more obscure novels. He’s most famous for Lord of the Flies, that post-apocalyptic vision of feral schoolboys trapped on a tropical island. I tried reading it to my son when he was about seven or eight. That was a mistake. He was trembling in fear after a few pages, puzzled about the violence, and I realized it was too adult for him. We abandoned it after a chapter or two.

After Lord of the Flies, Golding’s next most celebrated work is probably To the Ends of the Earth, the sea trilogy he produced towards the end of his life. This is a delightful series of books, consisting of Rites of Passage (for which he won the Booker Prize), Close Quarters and Fire Down Below, in which Golding tries to use as many nautical terms as he can muster. You can almost hear the relish in his voice as he presents yet another obscure 19th-century seafaring reference. In between there were a number of notable books: The Spire, about the building of a cathedral in the middles ages; The Inheritors, about a Neanderthal tribe meeting humans for the first time; and Pincher Martin, about a castaway on an island in the Atlantic. I’d recommend any of them. Golding’s the master of the plot twist, and none of the books are about what they appear to be. It’s better to read them than to read about them.

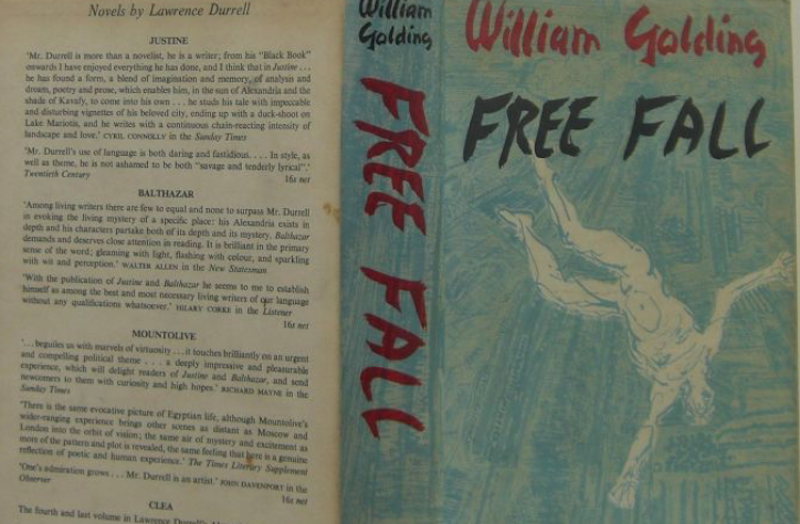

Free Fall sits somewhere in the middle. It was first published by Faber & Faber in 1959, then by Penguin in 1963. I read it in the early-1970s. I was a student drop-out in Cardiff at the time, sharing a house with a bunch of other hippies. We smoked dope from morning till night. Sometimes we’d go to the pub, when we had the money. Occasionally we took LSD and other drugs. I was kind of lost in the midst of all this, not knowing what to do with my life. Then I read Free Fall. It was like a revelation. The opening lines of the book sounded like something I could’ve written: or rather, like something I would’ve liked to have written.

“I have walked by stalls in the market-place where books, dog-eared and faded from their purple, have burst with a white hosanna. I have seen people crowned with a double crown, holding in either hand the crook and the flail, the power and the glory. I have understood how the star becomes a star. I have felt the flake of fire fall, miraculous and pentecostal. My yesterdays walk with me. They keep step, they are grey faces that peer over my shoulder. I live on Paradise Hill, ten minutes from the station, thirty seconds from the shops and the local. Yet I am a burning amateur, torn by the irrational and incoherent, violently searching and self-condemned.”

I don’t know why those words had such an effect on me. It was like they were talking directly to my DNA, as if they were pointing to my destiny. They set light to my imagination. They were like my own words, spoken to me by me, become vicariously alive in my head. Later, on the next page, he talks about hats. “I have hung all systems on the wall like a row of useless hats. They do not fit. They come in from the outside, they are suggested patterns, some dull and some of great beauty.”

There’s mention of his Marxist hat. I had a good friend at the time (still a friend) who was a hereditary Marxist, from a Marxist family. They were driven out of the Welsh Valleys because of their views, and were living in exile in England. We had many discussions and I too tried that Marxist hat on for a while. Sometimes I still wear it, just to feel its comforting presence. There’s much in Marx that makes sense. But reading those words back in 1972, it was like Golding was speaking directly to me, as if I was the one trying on different hats, and then discarding them in the hall.

The essence of the book is about an artist’s search for freedom. The narrator, a painter called Sammy Mountjoy, had been free once, but no longer was. When did he lose his freedom, he asks? He recalls a time when he was a child. He was sitting on the stone surround of a fountain in the middle of a park. It was sunny and warm, and there were banks of flowers, red and blue. He was listening to the sound of the water as it plashed and splattered in the surrounding pool. He was sitting on the sun-warmed stone wondering what to do next.

“The gravelled paths of the park radiated from me: and all at once I was overcome by a new knowledge. I could take whichever I would of these paths. There was nothing to draw me down one more than the other. I danced down one for joy in the taste of potatoes. I was free. I had chosen.”

That line about potatoes refers back to an earlier line when he says that free-will cannot be discussed or debated but only experienced, “like the taste of potatoes.”

I won’t go into the plot. Like many of Golding’s novels, it is full of twists. The centerpiece involves a torture scene when he was a prisoner of war. It’s psychological rather than physical torture, but it’s vividly brought to life in Golding’s painterly prose. For all that I had identified with the narrator’s voice in the beginning, it was clear that his life story wasn’t my own.

But those thoughts about freedom have stayed with me ever since. What exactly is it? I too, like the artist-narrator, feel a grievous sense of loss at its disappearance. Not political freedom. In the Capitalist world there’s no such thing. Money rules this world, and those of us who aren’t rich are only free to live in the world that the billionaires have constructed for their benefit. We’re free to use their services, to buy their goods, to consume their media, to support their wars, but not free to decide what kind of a world we’d like to live in. But there’s another sense of the word: that “taste of potatoes” that the narrator describes. I’m aware of its loss every second of my day.

It’s hard to pinpoint what I mean by this. I make several choices every day. Whether to go shopping or to go for a walk. Whether to write or to listen to the radio. Whether to watch a film on Netflix or to watch videos on YouTube. Whether to eat toast or porridge for breakfast. But they’re all false choices. It doesn’t really matter which of them I choose, I’m still not free. All of them exist within the constraints of an unfree life.

It has something to do with the loss of imagination. Freedom and imagination go together. You need to imagine new scenarios to create new choices. My choices all seem to come from the same bargain-basement shelves of proprietary products in the ideological supermarket of life under capitalism. They don’t offer real choice, only the illusion of choice.

Take those walks, as an example. I try to walk most days. There are woods at the bottom of my road: Blean Woods, one of the largest areas of natural woodland in Southern England. It’s very easy to get lost in those woods, but I never do. I always walk on the same paths, because I don’t want to get too far from home. As a child I would’ve loved to have got lost in those woods. As an adult I prefer to avoid it.

I’m also aware that I’m not really there half the time. I’m lost in thought, remembering this past conversation, or rehearsing that future encounter. I have to remind myself where I am. I’ll halt on the path, and try to notice the bird song and the rustle of the trees, but, once on my way, will quickly find myself lost in thought again.

This isn’t real freedom. I’m trapped in the never-ending echo-chamber of my internal dialogue, which serves as a kind of barrier against the real world. It’s like being in prison. I see the trees, but don’t see them. I hear the bird song, but don’t appreciate it. I breathe the air but forget to drink in its fragrance. I can’t dance. I can’t sing. I can’t paint. I can’t do calculus. I can’t play a musical instrument. What happened to the sense of limitless possibility I had when I was a child? Without these things, what freedom is there left?

There’s a TV interview with Golding dating from just after the publication of Free Fall. It was for a BBC program called Monitor. He was still a teacher at the time. He held his two hands in the air, about three feet apart. He said, “I plan a novel from the beginning right to the end, before I write anything, in detail. I see it in the air as a kind of shape about so long, from here to here, and then the detail begins to fill in and I work it out almost to the last flick of an eyelid. And then I write through.”

That’s interesting because it means that he allows his central character no freedom at all. Even while Sammy Mountjoy is bemoaning his loss of freedom, Golding has his life all mapped out, “to the last flick of an eyelid.”

Golding was unable to write after the publication of The Spire, due to a coruscating review on the BBC. He was a sensitive man, thin-skinned in the extreme. He suffered from writer’s block and didn’t publish anything from 1971 till 1979. Even while I was discovering his writing, he was locked out from the writing process, unable to put pen to paper.

Looking back it seems I missed an opportunity. I might’ve gone to see him, as Bob Dylan went to see Woody Guthrie, but it didn’t occur to me to do so. I was much too busy smoking dope and thinking about myself. I’d already lost my freedom by then. He might’ve welcomed a letter. My enthusiasm might’ve inspired him. We might have become friends.