The royalty I reference is my mom. She squired me throughout my awkward age—too young to drive, too old to be seen being driven by one’s mother. Call it My First Catch-22. These days, it might not apply. All I know is, in 1963 this was a window of vulnerability akin to living in mom’s basement, except on four wheels. Not below grade, but far worse in plain sight, on the streets where I might be forced to live by my fists.

So I got my slouch on and kept my head about level with the glove compartment. I wanted to tell my mom it wasn’t about her. Yet important as her feelings were, I had more mission-critical issues on my mind. Like my 13-year-old cred. Was I tough enough? Had I savoir-faire to spare? Just yesterday it was 1960 and I was already thinking outside my Hush Puppies.

How far outside? Moscow. London. Sofia. Brazzaville. Thanks to my short wave hobby, my world, at least the one between my ears, exceeded Heaviside Elementary School by about 25,000 miles, depending on ionospheric conditions. Sitting at my desk, I might look like I was screening a hygiene filmstrip, but my thoughts were very elsewhere.

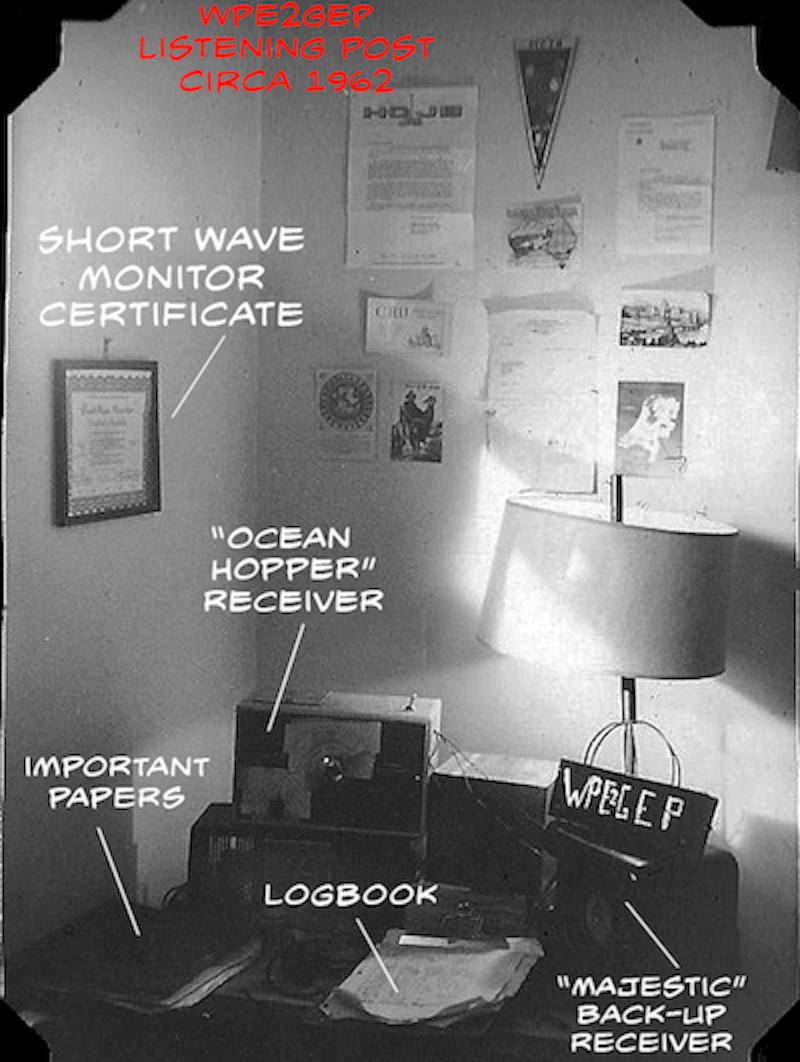

Once I got my sixth grader’s short wave legs, my beat expanded well beyond Piccadilly and Red Square. Hearing the BBC’s definitive “This is London” direct as WABC from New York became routine. Eavesdropping on the North American Service of Radio Moscow was a snooze of harvest stats and 20-minute musical interludes by the Red Army Chorus. Once I’d been and done both these bores, I listened for bigger game of smaller stations and weaker signals like Voice of Guyana, remember Cheddi Jagan? I worked wonders with my three-tube Ocean Hopper receiver. I could handle it, you know? I was a Registered Shortwave Monitor, issued an alphanumeric call sign not unlike those issued by the FCC to ham radio operators who take tests for the privilege. My cert arrived bearing my new Short Wave Monitor identity, WPE2GEP.

You might wonder, if not the Federal Communications Commission, then what controlling extra-legal authority issued my certificate?

Well, it wasn’t just any goofy magazine. Popular Electronics came up with the pretend call sign scheme, albeit a variation on a familiar theme. In the 1930s, Ur-geek publisher Hugo Gernsback entangled Short Wave Craft readers offering membership certificates in his “Short Wave League.”

To qualify for my official identity, I was required to cut out a form from Popular Electronics and fill in details about my radio equipment. I enclosed a small fee to cover postage and handling. And after a decent interval my suitable-for-framing cert arrived, signed by three executive staffers at the magazine, who might as well have been Dr. Howard, Dr. Fine and Dr. Howard.

Frankly, I was of three minds about short wave certification. My right brain died of misgivings in the fetal position. My left brain died laughing. Ever the survivor, my crocodile brain bucked-up and boarded a city bus to go certificate frame shopping.

In search of identity, we do whatever it takes to establish ourselves beyond ourselves. What’s more, wasn’t enough to be certifiably WPE2GEP. Photographic and presentation purposes called for signage.I anticipated guests inspecting my short wave monitoring station/childhood bedroom, including a bunk bed topped with my younger brother’s eyeless plush rabbit long ago squashed into a beige turkey loaf. Gut level, everybody knows great signage can mitigate bad optics.

So I sawed myself a strip of Masonite, painted it black and hand-lettered my provisional identity in large white letters and conspicuously positioned it on my monitoring desk, i.e. my parents’ cast-off gimp card table. What was I thinking? Very hard to say. I wish I could tell you it was that off-brand regional cola that came with a peyote button in every bottle, but nah, we were a Coke family.

Now about those short wave vanity plates that never happened.

In 1963, New York began issuing call sign license plates to FCC-certified ham radio operators. Popular magazine-certified short wave monitors like myself with pretend call signs were not eligible. Still not old enough to drive or own a car but studying hard for the ham radio test, I wondered if there was a way to leverage my extra-legal radio status into some form of vehicular signage.

Nuts, of course.

Sulking in the front seat, as my mom drove us to Lafayette Electronics to buy a hank of antenna wire, I wasn’t sure if I’d be less or more embarrassed with a hand-drawn WPE2GEP file card taped to the way back window of my mother’s Dodge wagon. Fat chance though. Same for a bumper sticker, likely as oversized ruby-eye skull mud flaps.

Top it off, about the same time, I discovered my parents considered signage on clothes equally distasteful. I stenciled WPE2GEP on a sweatshirt, and faddishly VAT 69 on another and was told I wasn’t wearing those to school. Well-digger cold matter-of-fact no, in a tone reserved for describing serious outliers as “unsavory.”

Stymied.

Once I got a real ham ticket, my mom still couldn’t get vanity plates because it was my ham license, not hers. And when I got my own driver’s license, I’d have to get my own car to get my own ham vanity plates. My larval identity was not to be leveraged, hypothecated, or spun before its time. The optics were intractable, no matter the prism through which they were seen. Nothing to do but drill down on Morse code, bone-up on radio theory and government regs, strap-in and take the test, and at last get licensed by the federal government to transmit, not just listen.

If now was then, WN2EXW would have been my first tattoo.