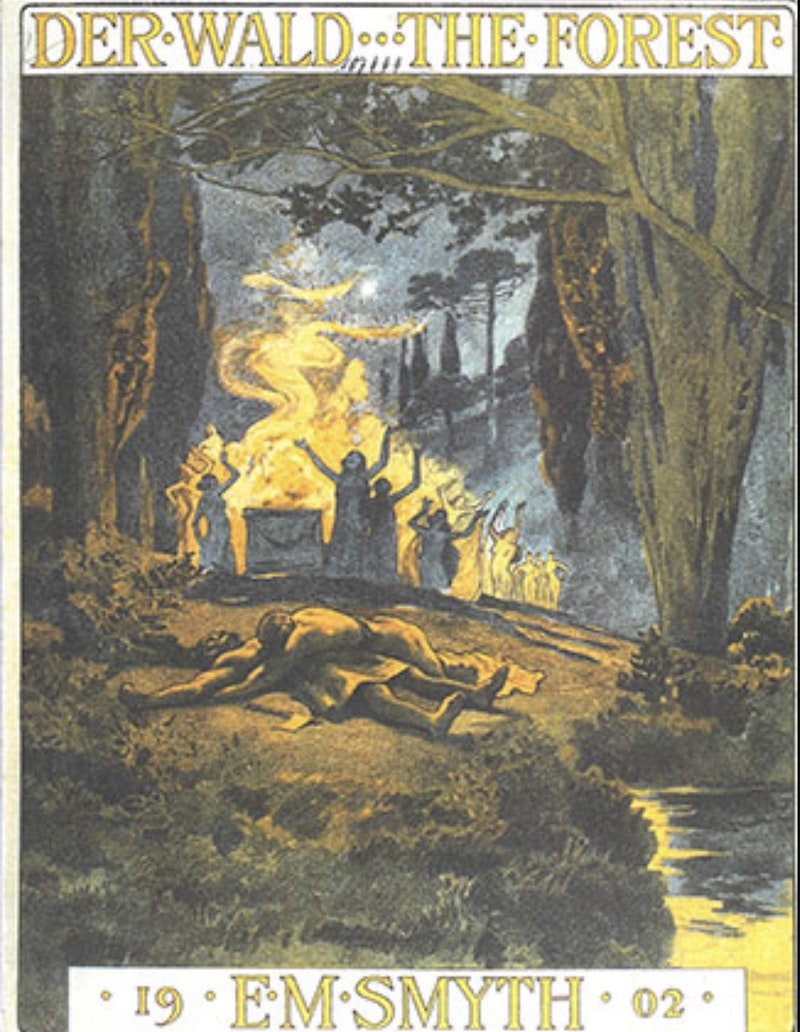

The English composer Ethel Smyth’s Der Wald was the first opera composed by a woman performed at New York’s Metropolitan Opera. Its premiere was on March 11, 1903. Maurice Grau, the Met’s manager, had found Smyth a tough, practical negotiator with a keen sense of the bottom line: he told her “You certainly are a businesslike woman.”

The Met’s second opera composed by a woman opened December 1, 2016, a mere 113 years, eight months, and 21 days later. This remarkable gap suggests an institutional bias against women composers at the Met.

I first heard Smyth’s work on a CD of British orchestral overtures, which included the overture to her comic opera The Boatswain’s Mate. There she quotes in full the music to her feminist anthem The March of the Women.

Out of curiosity from my enjoyment of Smyth’s music, I learned that Cicely Hamilton, one of her many friends, had set lyrics to the music. I looked them up. One passage reads:

Strong, strong, stand we at last,

Fearless in faith and with sight new-given.

Strength with its beauty, Life with its duty,

Smyth was one of 100 women arrested during a suffragettes’ demonstration, she conducted a performance with a toothbrush through the barred window of her cell as her comrades marched and sang the hymn in the quadrangle of Holloway Prison. There she’d spend two months as an involuntary guest of His Majesty the King. One can only imagine the response of Major General John Smyth, her father, who believed that a lady performing music in public was very nearly akin to a streetwalker. To her friends and admirers, she was a hero.

•••

Autumn has come again to Antrim, New Hampshire. The red and gold leaves litter my front lawn inches deep. The evenings are comfortably cool. Clouds of calling birds fly south.

I saw my first moose a few days ago while driving to town. My house is on Clinton Road, which rises from the valley of the North Branch River, passing between the heavily forested Meetinghouse and Holt Hills before abruptly turning south toward downtown Antrim. The car was about halfway up the rise, about a half-mile from my house, when I saw him. He was standing in the middle of the road, appraising my car. A bull moose often considers a moving automobile a four-wheeled challenger, best opposed by an immediate charge. I slowed, undesirous of a close encounter. My car would kill him. His 600-pound carcass would fly over the hood, through the windshield, and into me. It’s happened to others. We’d both lose.

But this wasn’t our day to die. The moose sauntered to the road’s left grassy margin and turned toward town, shifting to a calm, fast walk. I slowly came parallel to him, as far to the right as I could. He was an adolescent, just over five feet tall at the shoulder, not counting the neck, head, and underdeveloped, velvet-covered antlers. We’d traveled together some 300 feet when he saw a gap in the shrubbery and vanished amidst the trees of Meetinghouse Hill.

Parenthetically, the plural of moose is moose. The word was directly taken from Algonquian, an indigenous American language. Moose kept the same plural ending in English as it had in its original tongue.

A flock of some 36 turkeys—Mimi and I have counted—periodically passes across our land, quietly pecking at seeds and insects as they continue their migration in search of food. Apparently, they travel a circle of about five miles. Last week, I was taking my daily walk when, suddenly aware of a soft clucking, I found myself alongside the flock, which quietly melted into the shrubbery north of Cemetery Road.

A bear has come by night to raid our garbage. He pulled open one of our bins, tipped it on its side, and worked his way through the trash. He was probably disappointed. Most of its contents were gleanings from our cats’ litter boxes.

Squirrels and field mice seem to find our house attractive as the season moves toward winter. Built in 1826, survivor of a 1922 tornado, it’s probably sagged enough to allow them a few means of entry. However, they face implacable enemies: Cordelia, Hotspur, Orsino, and Viola, our cats, all named after Shakespearean characters, each ruthless as Richard III. Once or twice a week now, I find a dead rodent on the floor outside my bedroom door. Clearly my squad brings me tribute when they overcome their ancient prey, even if to show they’re earning their keep.

Such events are a natural part of New Hampshire rural life.

•••

I was driving to the Post Office to mail a large envelope to one of my brothers. The postal regulations have become so complicated about calculating postage, which is now based on an envelope’s size, weight, and thickness, that standing at the counter may be the surest way to send one’s larger envelopes.

The clerk glanced at my name in the return address. She looked up. “You’re the guy who writes about horses,” she said.

Flattered, I said yes. In New Hampshire, sometimes everyone seems to have had at least one memorable equine encounter. After last week’s lesson, I went to Shaw’s in Hillsborough to refresh the household larder. I was in very dusty riding boots and breeches. A woman on line before me looked and quipped, “I thought I was the only person who went shopping like that.” I grinned. She asked where I rode. I replied that I was learning to ride at Southmowing Stables in Guilford, Vermont. She replied, “You must be William Bryk.” There’s something refreshing in being known to one’s neighbors for adventures and misadventures on horseback instead of politics and journalism.

The adventures have come to me through the tutelage of Dorothy Crosby, the instructor who has guided my efforts since I first put my foot in a stirrup nearly six years ago, and three horses, Julio, a stubborn but endearing Morgan-Percheron mix;Toby, an elegant Thoroughbred formally known to the Jockey Club as Noble Victory; and Merlin, my present assigned horse, an 1800 pound paint rescue colt of unknown ancestry, enormous appetite, and unpredictable attitude. Nonetheless, he’s teaching me a lot about how to get along with a horse. The misadventures usually come through my inexperience. There’s no such thing as a bad horse: only bad riders.

After a tiring lesson last month with Merlin, I groomed and returned him to his paddock. I locked the gate and, suddenly exhausted, I leaned against it with my forearms. He ambled back and began kissing my hands. I turned them over to show I had no treats. He kissed my empty palms anyway. I was surprised and touched. When he was done, he walked away.

•••

During this past Friday’s lesson, Merlin resumed being difficult. As long as I kept him at the trot, he was fine. Then he’d slow and begin yanking his head toward the arena’s floor. There’s a careful balance between firmness and roughness that I occasionally fail to maintain. Merlin was signaling that my handling of the reins was a little rough on his mouth and he wanted that stopped, sooner rather than later. I did my best to accommodate him.

After my lesson, a group of girls and young women from Vermont Academy, a co-educational college preparatory school with an international clientele in Saxton’s River, Vermont, put on a show for their parents. I stayed to watch Merlin at work with another rider in the indoor arena. He gave Elena, a gifted equestrian, no trouble at all, which says a great deal about Elena’s horsemanship.

Then the riders went to the outdoor arena, where jumps had been erected. One after another, the young women and their horses went through their paces. I learn by observing other riders guide their mounts. These young ladies performed beautifully.

Though shaped like a beer keg with four legs, Merlin was trained to be a hunter. He’s brave, powerful, fast, and graceful. Elena took him to the trot and then the canter. They circled the arena. Then he thundered for the first fence.

Three strides from the fence, Elena leaned forward almost to Merlin’s neck and flying mane, her knees at his upper sides, asking him to jump.

Two strides from the fence, his hindquarters’ huge muscles bulged, he raised his forelegs, the hind legs pushed off like pile drivers, and he soared over the fence like an angel. Merlin showed us, as Smyth’s music inspired Cicely Hamilton to write, strength with its beauty.