The child detected something in the air, felt threatened by the bodies that lay dead on the floor and out in the yard, and toddled toward a low end table upon which were laid a couple of knives and a sort of handaxe type armament with a curved, multi-pronged blade. There it fumbled with its uncoordinated, underdeveloped hands at the handle of the first of one of the knives, then another. Feeling uneasy, the man grasped the handle of his shortsword, slid it carefully out and into the light of day, its blade gleaming under the fingers of golden yellow that reached through the trees and the open fusuma behind him. He pointed the sword toward the child, but it seemed not to understand even the intent of the gesture, first staring dumbly as it attempted to ingest one of its stubby fingers then most of its fist, its long eyelashes batting stupidly a couple of times as it fixed its gaze on the man, not the sword.

The man grunted fiercely to that effect, that the child ought better to mind the blade and its position and its movements than the face of the one who held it. Nonetheless, his demeanor softened for an instant, and in that instant the child made a movement, with a surprising sort of craftiness and crude agility, to get around the length of the sword. The man growled in anger, as much at himself as this damned youth, and in a flash flicked the sword’s tip toward and then away from the left eye of the child, swiping it from its socket and flinging it through the fusuma and out into the clearing.

The eye’s deprived owner dropped its weapon and toppled not only to the hardwood floor but back into the earliest stages of childhood, its brief flirtation with an eerily precocious aptitude for combat plucked from it like the eye from its skull. It writhed in a kind of agony its system was unequipped to even begin to process and so its cries were strangely muted.

The man nudged the child with his foot, the bottom of his sandal forcing it onto its back, put its throat to the end of his sword, close enough to impaling it that fresh blood welled at the point of contact in addition to the torrent of crimson flowing forth from its vacant eye socket and through the fingers of its attending hand. Even as the child gasped and moaned trying to make sense of all this pain and fear, its remaining eye had a sort of calmness that unnerved the man greatly.

He leaned forward, but not too far forward, reassured by the blade that separated him from the babe. He barked some words that’ve been lost to time but then, the one he said and after repeated, were etched firmly in the very fabric of both his and the child’s being: “Miyamoto. Miyamoto.”

Servais had somehow convinced one of his neighbors to swap their red convertible Malibu for Powell’s shitty, pizza-scented Ford Focus. The grizzled former catcher, once noted for his clubhouse leadership and ability to call a good game, was now more interested in the Budweisers he shotgunned by twos. Burping loudly and a bit of foamy beer trickling down his chest, which he’d bared to soak up some rays during the drive, Servais looked over at Powell, noted the tension in his neck and shoulders, the nervousness in his reddened eyes, the twitching of his jaw.

Servais clapped Powell on the back, gave him a squeeze on the shoulder and trap. “Y’a’right, Kid?”

Powell took a deep, shaky breath, glanced at Servais. “Pass me a beer, will you?”

Servais pulled two frosty brews out of the small Igloo cooler at his feet, popped their tabs with his forefinger and passed one to Powell. “Here ya go, Kid,” he said, then, trying to lift his friend’s spirits and perhaps convince himself as well, said, “Cheers to ya, Kid. Everything’s gonna be a’right,” and clanked his can against Powell’s, creating a bit of frothy discharge from each in the process.

Powell took a quick look at the sides of the road ahead before a healthy, restorative sip of beer. He exhaled, satisfied for the moment. Servais turned on the radio. “L.A. Woman” by The Doors was playing, already deep into its iconic intro.

After no more than 30 seconds of peace, beer, music and sun, Servais shouted suddenly, “Pull over!”

Powell jumped a little, sloshing a bit of sauce on the steering wheel. “What? What is it?”

“Pull over, pull over!”

“Gosh, I will! Just… just calm down!” Johnita Luxton urged, her agitation obvious.

She checked the rearview mirror and slowed and steered over onto a little gravel driveway with a length of chain running across it a few feet in, denying access to the lot beyond. Johnita looked at The Reformed Genius, who was extremely worked up in a way she’d never seen him. Many times before he’d been near some sort of ecstatic mania at having put the finishing touches on a Miracle Murder Machine or concocted an Evil Scheme, worked into a lather over having squeezed ransom money out of someone or other, but this was different… he was scared, upset, worried about something. And then he sprang from his seat and out of the car.

“Wait! Where…?” she called after him.

“Ethel! Etheeeeel!” The Reformed Genius shrieked, ducking under the aforementioned chain and running as fast as his old toothpick legs would carry him.

TRG fled into the empty crushed gravel lot of what appeared to be some sort of disused manufacturing facility, a large brick building with several smokestacks and big hinged four-panel windows, many of which had large holes of abstract shapes in them, thick, tall sliding wood doors with lengths of heavy-gauge chain looped around their iron handles, a murder of fat black crows cawing from their shared perch on a rooftop ledge. He stopped at a metal door at one end of the building that was warped horribly and hanging by just one hinge, barely attached.

“No, no, no, no!” TRG fretted in a kind of panicked mantra of disbelief.

Johnita, who’d taken off her heels so she could cover the ground between her and TRG more quickly, breathed rapidly as she came up behind him. She made a mental note to cut back on the cloves; they weren’t really doing much for her nerves and now were playing hell with her lung capacity. Plus, frankly, a lot of people thought the habit was a pretentious affectation. Did they even have nicotine? Just smoke a regular cigarette.

“What is it? What’s… what’s wrong?” the attorney asked breathlessly.

TRG turned around, his face white as a sheet. This was his normal color, of course, but now the sheet in question would’ve been one from a wash cycle with a few splashes of bleach. Ya boi was in a bad way. “It’s Ethel,” he said with a sudden, eerie calm. “She’s… she’s… gone.”

“What do you mean she’s gone? Gone where?”

“She’sh a dansher… a shtripper… she’s… gone…” Berkman slurred repetitively, his head pressed against the wall of the telephone “privacy pod,” the insistent, infinite throb of “Cotton Eye Joe” reverberating both within the wood and within Berkman’s skull, his soul.

“Brinkman! Get a hold of yourself, man!” Leeds barked. There was a frantic short succession of tapping followed by several bloops, beeps and high ringing noises. “Fucking goddamn stupid hedgehog!”

“It’s,” Berkman paused to burp and retch. A teetotaler, the shots of whiskey he’d switched to from club soda were not agreeing with his stomach and were still burning his throat, but he needed to “die his brains,” as Powell and Servais had often described the need to dull one’s senses in the face of some great, unendurable pain, “Brick… Berkman… sir…”

“Brick Berkman? You must be Oscar’s brother. How’s he doing? What’s he found out?” Leeds, now sounding more “present,” inquired. “Velma!” he shouted suddenly, having taken the receiver away from his mouth. “Find me some cheats! I’m stuck on this goddamn underwater board!”

Leeds muttered angrily for several seconds about “stupid swimming levels ruining the sport,” during which time Berkman’s drunken but insufficiently “died” brain replayed, in agonizing, horrible detail, the scene of Emily Twiggs, dressed in a Catholic schoolgirl outfit, her brown hair in pigtails, her normal contacts replaced with glasses, a look of a strange brand of contentedness replacing the early nerves as she danced provocatively, looping a pink feathered boa around her thin, fit legs, their olive skin glistening with scattered beads of sweat. She kicked her left leg to the side, then, throwing the boa to a leering, practically drooling goon at the ledge of the stage, lifted her leg with both hands, pulling her long white sock down even as she raised the increasingly bare limb up, up, up, to where her shin was parallel with her head.

“Berkman! Are you there?” cried Leeds. “Answer me! Can you hear me?”

“He’s in shock,” Powell remarked as a matter of fact.

Servais looked over his shoulder, a somewhat annoyed aspect to his tough, chiseled visage and in his intense dark green eyes. He returned his gaze to the man who lay writhing on the ground before him, a black snake protruding from the man’s mouth, its tail whipping and coiling as it tried to force itself deeper into his mouth and down his throat. Servais, taking the snake’s dark, wriggling body in his rough, leathery hand, tried to pull it free, but even this grizzled hardman couldn’t yank it loose, the serpent seeming to have a preternatural strength to match its undeterrable instinct to burrow into this person’s guts and his very soul. The man was gagging, his eyes watering and wide with terror.

“Bite! Bite! Its head off! Bite!” Servais roared, furiously, hatefully, pityingly, all his emotion merging and rising from him in this series of forceful exhortations.

Powell held the man’s dog, a small collie, close to his body, the dog worked into a trembling panic. With the animal beneath his arm and pressed to his side, Powell watched the man, the whites of whose eyes were as wide as silver dollars, darting to and fro but finally locking on those of Servais, still holding the snake but now putting the other hand on the man’s chest reassuringly.

And so the man bit down, the muscles in his jaw tensing and tightening and dark, almost black blood spurting from his lips, the sound of his teeth crushing and snapping the bones below the snake’s head cutting through the frantic panting and whining of the collie and the sharp, halting breaths of the man and the pounding of Powell’s own heart in his ears. He spewed the head and a spray of the serpent’s blood forth, ejecting it into the roadside ditch.

Servais looked at Powell, a grin on his face, his eyes alive with a sort of happiness that went beyond mere relief, and the young man exploded into a fit of giddy laughter. Servais helped him to his feet.

“What’s yer name, kid?” Servais asked, knocking some dust off the kid’s shoulders and back.

“Shepard,” the young fellow answered after clearing his throat several times. “My friends call me Shep.”

“Get Shep a beer, will ya?” Servais suggested, hooking a thumb back toward the Malibu.

“No more booze for you!”

“What?” Berkman snapped aggressively at the bartender.

“You can barely keep your head off the bar as it is, honey,” the bartender said, taking a gentler tone now.

“Get the man a drink, toots! Can’t’cha see his heart’s been busted?” The Chief demanded, having sidled up undetected, aided in that accomplishment by both the latest repeat of “Cotton Eye Joe” and Berkman’s worsening inebriation. He took a big loud sip of his “Sugar Tittytini,” a blue concoction that looked almost radioactive, through the curly neon pink straw that protruded from the absurd, ornate, oversized goblet in which it was served. “And how ‘bout another one’a these for me, gorj?” he asked, wiggling his thick, fuzzy eyebrows as he drained the rest of the glowing beverage and set the glass on the bar.

Berkman looked up with bleary, filmy eyes, their quality far off and unfocused. The bartender gave him a sad smile, then looked at The Chief.

“He needs to be home in bed! But,” she said reluctantly and started making the drinks, “You’re his father. I guess you know best.”

The Chief gave Berkman a little squeeze. “A well-liked man will never want, my boy!” he said, exalting in his triumph and celebrating by inserting a cigarette into his ear. “She thinks I’m your pops! Ain’t that somethin’? Ha!”

“Death of a Salesman?” Berkman offered, the dialogue having penetrated the sauce-addled fog of his senses somehow.

“Hah?” The Chief asked as the last of the ciggy crossed the threshold of his earhole and passed into the great beyond.

“‘A well liked man will never want,’” Berkman paused to hiccup. “That’sh… that’sh… Henry… no, Arthur, uh, Miller.”

“I dunno what that means, Buster Brown. Alls I know is we got drinks on the way and I think this bird has the hots on for yours truly. Ain’t life grand!”

“Don’t be so sure of it,” Berkman replied as the drinks were served and he paid with the last of his cash. He took a gulp of his Coast City IPA, a hoppy brew noted for its “lively, crisp flavor with traces of citrus and piney, heady aftertaste” by the snobs who treated beer like wine (“The ideal beer to pair with a nice piece of free-range chicken grilled over a bed of glowing cedar chips and fresh field greens,” observed popular “beer critic” Isaac Suddington III in a video review for the Anytown Survey of Food and Drink) to be fetishized, but favored by those looking for a buzz due to its 16 percent ABV. “Things change,” he said enigmatically, borderline nonsensically.

Pillowface handed Emily her sweater as the latter finished buttoning up her blouse.

“You did pretty good up there, rookie,” she said, attempting to affect the demeanor and tone of a seasoned, world-weary veteran who’s taken some greener-than-goose-shit newbie under their wing. Perhaps a Servais type. “Got a smoke?”

“I’m sorry, I don’t smoke,” Emily answered, sliding into her sweater. “I think I’ve told you that three or four times now, Pillowface.”

“Oh yeah,” Pillowface said. “Guess I forgot.”

“It’s okay,” Emily said. She brushed her long brown hair a little with her fingers, then picked up her purse and rummaged through it for her compact and lip gloss, but stopped before applying any and looked at Pillowface, asked nervously, “You really think I was good?”

Pillowface took a short offered by one of the other girls, lit it and coughed, a couple of feathers floating out of her mouth after. “Darn cough,” she said, then took another puff. “You were good. Trust me, greenie.”

Emily fought to keep from smiling but couldn’t help it. She had heard that “sex work is good, actually,” even written a few pieces echoing that sentiment for mags like “Highlights for Children,” but she hadn’t expected it to be so invigorating being up there on stage with all those eyes on her and her inhibitions falling by the wayside. Previously her sexuality had been somewhat buttoned down and repressed, but she felt unshackled now, as if the Jaws of Life had been used to cut the shackles apart. She made a mental note to use that phrase in the piece she was already working on in her head for Moustache, about this wonderful new work and the feelings it was stirring up within her.

“I can feel it inside me: something is very, very wrong,” The Reformed Genius said darkly.

It didn’t take any genius to see that, Johnita Luxton thought. In addition to the door to the shithole abandoned factory having been mangled and largely torn free of its hinges, the inside of the place— furnished and bedecked in the manner of a Postwar suburban American middle-class home, the “little place by the docks” TRG and Ethel had, Johnita surmised with as much incredulity as anything else—there were signs of a struggle as well: broken glass, an overturned table, holes in a freestanding wall that divided the living area from the larger laboratory area where it was apparent that, Miracle Murder Machine or no, The “Reformed” Genius had been and still was hard at work on something.

Johnita’s puzzlement yielded to a growing annoyance and burning desire for answers. She stormed up behind TRG, grabbed one of his spindly arms and whirled him around.

“What the hell is going on here? What… what is this?”

“Excuse me?” Emily asked with uncharacteristic white-hot anger.

“I-I… I said what were you, you doing up there ‘dancing?’” Berkman probed, having regained a bit of lucidity in the bargain that had cost him some of his more general composure. The venomous sarcasm had all but sprayed from his tongue with the word “dancing.”

“I might ask you the same thing!” Emily shouted. “Come on, Pillowface, we’re leaving!”

Emily pushed past Berkman, not to mention The Chief, who was for his part silent save for the slurping of a bright blue drink in a huge margarita type glass with crushed ice and sugar cubes and pieces of fruit floating in it and an umbrella and salt on the rim and a curly pink straw. She looked at it again and wanted badly to know what it was, it looked so yummers, but now wasn’t the time to ask.

“What? I wasn’t dancing!” Berkman protested.

Emily made a frustrated noise, stopped in her tracks and balled her fists tightly. Her posture rigid as all hell, she turned around stiffly. “I meant what are you doing here! Here! In this… this seedy, yucky, sleazy, icky stripper place!” cried Emily.

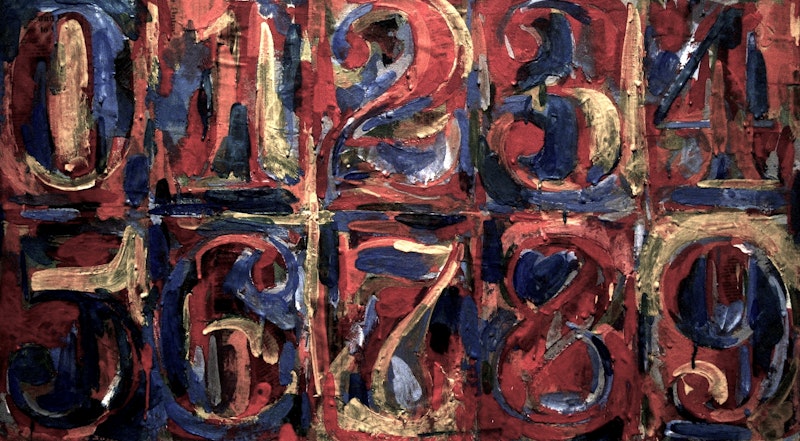

Miyamoto jolted awake, sat upright and threw the sheet off his bare torso. He touched at his throat, looked at his fingers. Seeing that there was no blood, he breathed, realizing he’d been holding his breath since the start that had roused him from his sleep. He looked at the wall: it was still there, that painting that had so deeply unsettled him some hours before. He didn’t know why he’d thought a painting might move or even disappear of its own volition, but he’d thought it a possibility all the same.

The soles of his feet touching the cool of the hardwood floor, Miyamoto stood, stretched lightly and then, feeling a compulsion similar to the one that had led to his lying down a while earlier, walked over to the wall and stood before the painting.

It was the painting “Figure Zero” by the American abstract expressionist Jasper Johns, an oil and collage work on canvas in its original form, but this was just a cheap reproduction on glossy paper, framed and hanging beside the little table in the “breakfast nook” of Miyamoto’s extended stay suite. Nonetheless, as he stood close to it— closer than he had before—Miyamoto began to feel light-headed and had a tightness in the very center of himself. He had to move away.

In the bathroom, he looked at his reflection in the mirror, at the empty socket from which his left eye had been plucked as a child. And he knew that he was not alone, either in the suite or, indeed, even in the bathroom.