If asked, Sam Lipsyte would probably tell you he hasn't killed himself because you can't masturbate postmortem. Plus, the kids.

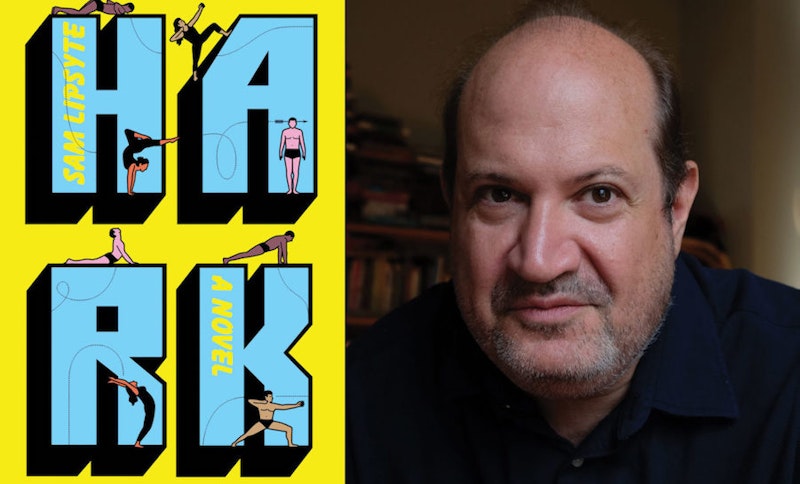

It's this ironic detachment that makes his short stories so compelling, and his novels so exhausting: vacation in the mind of a junkie and you can romanticize their desperation, appreciate the griminess like a dad would a Civil War site; stay too long, though, and the inertia of unsuccessful middle-aged men will drag you down, leave you feeling depressed and fetid, like you just ate an entire Styrofoam clamshell of takeaway Indian food. Hark—Lipsyte's follow-up to 2010's The Ask, a decorated but similarly frustrating read—is easily his worst book. Any surface level differences from his sad sack oeuvre, like the eponymous prophet figure or the little-mentioned communist land war on continental Europe, are ignored in favor of gazing at our protagonist's bloated navel.

That gut belongs to Fraz Penzig, Hark's 47-year-old schmuck of a hero. Surprise: he’s an overweight, over-educated Jewish man who no one respects. Like Milo from The Ask, Lewis from Homeland (2004), or Steve from The Subject Steve (2001), Fraz is defined by his fetishes, his appetite for disgusting foods, his artistic failures, his vocabulary. Fraz's interactions almost universally end with verbose admissions of his own ineptitude.

That ineptitude is the reason we're following him in the first place: he's an also-ran in Hark's burgeoning self-help movement, a walking mid-life crisis who no one wants to look at, let alone associate with. Fraz, unlike fellow Harkists Kate and Teal—the former bankrolls the movement; the latter running logistics—has no utility. Yet he sticks around, devoted to Hark's "focus on focus." And that's exactly what Lipsyte expects us to do: stick around, despite being treated like Fraz, out of the loop and always wondering what's going on.

This is the only novel that has left me longing for exposition. Lipsyte offers scant information on the Army of the Just, the red militia that has captured half of Western Europe at the story's outset. Likewise, little is said of the handful of U.S. presidents who’ve assumed office since Obama, just that they've spiraled the country close to apocalypse. Most egregiously, despite Lipsyte's technically deft yet contextually confusing use of free indirect narration, we never fully understand Hark himself, the maybe-messiah driving the action. The few glimpses we do get into his interiority—primarily through dream sequences involving a catfish and its late-night talk show—are highlights, demonstrating that Lipsyte can escape his horny, middle-aged mindset when he tries.

But he doesn't try. Instead, he fills space with useless dialogue, scenarios designed solely to show off his linguistic gymnastics and caustic wit, scenes that come across more as the product of mental masturbation than writing. He's still a funny guy, and each chapter has a chuckle or two, but every character sounds the same, has the same endless vocabulary, the same biting cynicism and ruthless mean streak, leaving me wondering what Lipsyte intended this novel to be. A Trump-era parable, I suppose. How boring.

Why does Hark want to help people focus "in the home or at the office?" What's the purpose behind his teachings? And how do they connect to greedy technocrats and global revolution. We never find out.

Hark has nothing. It establishes Lipsyte as a writer with a myopic vision, burdened by his neoliberal guilt, who, even if the world were ending, would only care about his dick and his stomach.