One of my older brothers puts little stock in extra reminiscing when the anniversary of a loved one’s death hits the calendar. He maintains that those who’ve departed are in his thoughts nearly every day, and while that makes sense, I do mark melancholy milestones. This week, I’m thinking more than usual about my dad, who was born on Nov. 30th, 1916 (and married the same day in 1940). As previously noted in this space, my father died young—a heart attack in 1972, years before transplants and bypasses reduced “cardiac event” fatalities—a few days after my 17th birthday. Not entirely uncommon, but devastating nonetheless for his five sons, none of whom had yet turned 30. There’s but one silver lining in losing your parents at a young age (my mother succumbed to brain cancer 11 years later) and that’s being spared the wrenching indignities that inevitably occur in the final years of an elderly person, whether it’s dementia, Alzheimer’s, cancer on top of cancer or just a body breaking down.

There’s a 13-year difference in age between my oldest brother and me, the caboose of the clan, and several times a year, maybe after dinner after the other guests have departed, we talk about our dad—also not uncommon, we all regarded him as a pillar, a stoic New Englander who never complained, didn’t gab much, but when he did speak it was notable—and because of the different eras we grew up in, we have singular memories. These conversations lead to a better understanding of our father, a more complete picture.

Before I was born in 1955, my family hopscotched around New Jersey, where Dad would find different jobs in his vocation as an engineer/chemist. A blank slate for me, obviously, as was the presence of grandparents, with the exception of one, gone by my birth. The two oldest boys have dim memories of my mother’s father, who was born in 1868, moved from Dublin to America, and became a cop, and later captain, in the Bronx’s Irish ghetto. He died in 1948. There are a slew of uncles, aunts, cousins—mostly on my mother’s side, since my father was an only child—whom I’ve heard about but never met. Excellent yarns about some real characters, and whether they’re apocryphal or not doesn’t matter so much. I still don’t believe there was an Uncle Oskar in the family—my leg pulled out of its socket—but there are old pictures of various O’Neills and an Uncle Jimmy to document their actual existence.

In the fall of 1968, I was the only boy left in the house, as the others were starting business careers and families or in college, so this is the era I can, and have, fill them in on. They used to josh that a permissive road was paved for me by their misdeeds—when my mom would gather the family to script a “public story” for, in retrospect, some really minor infraction—and that’s true to the extent that my parents were tuckered out with monitoring the kids.

For example, they were summoned to the principal’s office at Huntington’s Simpson Jr. High in the spring of 1970, an uneasy meeting since they were friendly with Mr. Bromsted. I’d produced a one-page mimeo mocking the assistant principal, a tool we called King Carl, and that caused a stir. Mr. Bromsted wasn’t a dummy, he knew the tide was turning, but felt compelled to inform his friends Kay and Hal about Rusty’s untoward behavior. It was all very cordial: my mother spoke about the First Amendment and didn’t cede an inch, while my father nodded approvingly. I was given a week’s detention, and after we left both said they didn’t like the potential “black mark” (college applications!) but were proud of me. We went out to dinner at Northport’s Waterside Inn, a favorite Italian joint.

My dad owned a car wash in Copiague, which was hit or miss profit-wise, and worked seven days a week, although he came home early on Sundays, or when it was pouring. On the latter occasions, we often went to Huntington’s local library for 90 minutes or so. He’d pore over a week-old copy of Barron’s, while I scoured copies of the British music newspapers Melody Maker and NME. It was just Dad and me, reading and joking later in the car, our own private world.

He later sold the Long Island car wash, and attempted finding a job in New York City’s bureaucracy, but in his early-50s was told that while qualified, he was too old for this or that position. Today, such a bald explanation would result in a lawsuit and a bump to the family coffers. When I was in 10th grade, he bought a different car wash outside of Trenton, NJ, which sucked since I didn’t want to move. As it happened, our worn-down split-level was on the market for well over a year—meaning he came home on weekends—and finally sold in ’72 for a paltry $19,000, about the same as the purchase price in 1953.

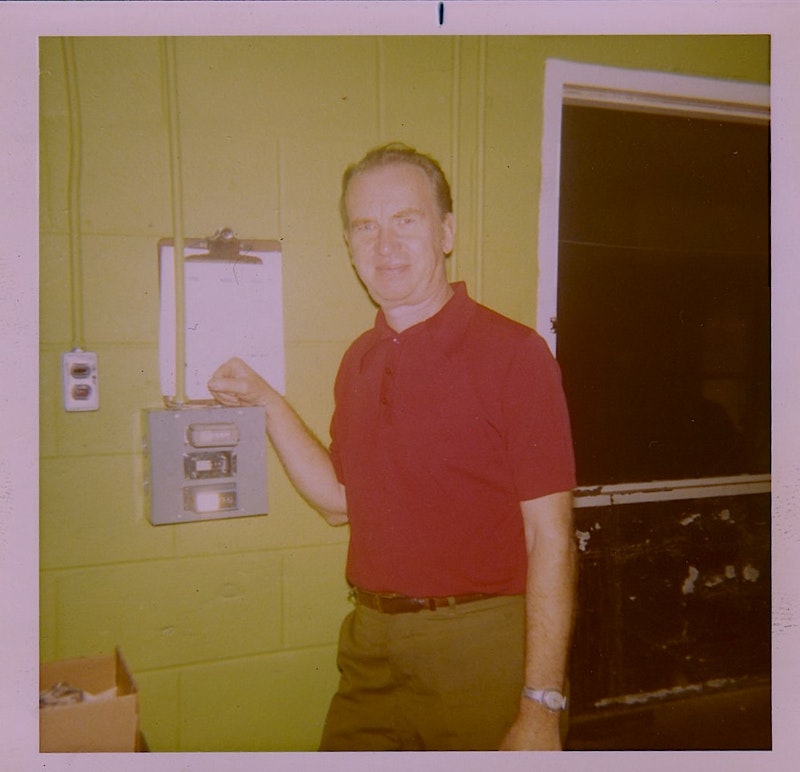

He’s pictured above at the Hamilton, NJ car wash in the fall of ’71, at 54, and, as it turned out, less than a year before he died. I visited a few times, hung out, smoked a reefer on the sly, and then we retired, after getting take-out, to this dump he rented in Trenton. Again, he never carped about the situation, although I’m sure he thought, Gee, who’d have thought at 54 that I’d be living in a walk-up apartment.

On weekends at home in Huntington, he asked me to help him with some accounting for the business. We both knew, but didn’t verbalize, it was a ruse to spend time together. He was a numbers whiz, but wanted to give his youngest son some rudimentary experience. I enjoyed it: math came easy to me, and it was pretty cool to discover some month-to-month trends in the business, and I felt like a million bucks when Dad said, with a big grin, “Nice diagram, pal, that’ll come in handy.”

It’s these small moments, and triumphs, that I think about when remembering Dad in the last years of his life. He didn’t have many friends in middle age—that was mom’s department—but loved carving out time to spend one-on-one time with each of the five boys. Can’t ask for much more than that.

—Follow Russ Smith on Twitter: @MUGGER1955