It was the second Monday of October and Dashwood Bryant was on his way to his bookshop, taking his usual morning constitutional to savor a smoke and his thoughts. He was thinking, mainly, of last night's dream, a dream that reoccurred, a little differently each time. Differently, but always in a big city, commencing on a crowded avenue until he shunted onto a quiet side street, then down a desolate alley. At the end of the alley was the barefoot calico gal on the porch of her tarpaper shack. On this morning’s walk he stopped, snapped his fingers once, tossed the cig into the gutter, and resolved to find her. He put a note in the shop’s window stating he'd be closed for a couple of days. Then he beat a beeline back to the boarding house, to the backyard barn that housed his powder-blue VW Beetle, and putt-putted away.

No clear idea of how to get back to her shack, Dash counted on retracing his miles from where he'd begun the return trip north years ago. It took a few hours to get to the starting point. Then he tried to locate the back roads he'd taken. There were missteps, and backtracking, but eventually he found his way. Sights he'd only seen once, years ago, rang memory bells. His pulse quickened, he was zeroing in. She was just around the corner, he was certain. He still didn't know what he’d say to her. This was all so crazy, silly even. He didn't rehearse any lines; he just put his faith in God or Fate or whatever you want to call it, to guide him when the time came. All would work out, he knew.

He drove up a hill, and at the top, where her property had been, there stood a half-dozen brand spankin’ new A-frames. In front of one, a man was mowing a thin new lawn with a reel mower as the sun descended.

"Sure, we've been here since June, when the places first went up for sale. Nice little community we have here. Neighborly, young, families." To the back, kids were playing army. "Bang! You're dead!"

"The woman who lived here, do you know her name? Where she went to?" Dash struggled to keep desperation from his tone.

"No, no idea. Maybe in town someone would know. Try Pat’s Diner. Ask for Pat. She knows everybody and everything!"

"Thank you.”

Dash scooted to town, and parked. He felt thin and airy, insubstantial, walking on solid concrete. It was easy to find Pat's Diner in this tiny town. At the counter he ordered dinner: a hamburger deluxe and a Hire’s.

He introduced himself to Pat.

"Oh, you're looking for Betsy Donner. Ain't no bad news, is it?"

"No, not at all. Kind of hard to explain, really." Dash felt his face reddening. He took a sip of soda and looked down at Formica. Formica looked back. He could almost hear it chuckling at him. "Foolish mortal," it seemed to smirk, “you thought you could embark on an odyssey and claim your ephemeral queen? Well, ha ha! You've always been a goofball."

"I just met her once, really. I don't know. I guess I'm an idiot..." Dash wasn't sure if he was speaking to Pat or to Formica.

"Well, all I know is that Betsy sold that land, got a pretty penny, moved north to live with an aunt. Don't know much about her, kinda kept to herself. Wasn't from around here, original."

"Thank you. Thank you for your help."

Deflated and feeling quite the chump, Dash drove to the outskirts of town, rented a room at a small motel and turned in early. He stared at the ceiling, pondering the futility of everything, just everything, before sleep claimed him. Slumber didn’t offer the solace of a mystery-girl dream. Instead he dreamt he was running in an endless desert of white sand under a relentlessly azure sky, searching for a chimerical sun. The next morning he headed home. He didn't bother to turn on the car radio, almost wary of what he might hear.

Along the way, Dashwood Bryant motored up and down hills, rolled into small towns and rolled right back out, around bends, headed along two-lane blacktop straightaways until, the sun setting, expedience dictated he get on an interstate.

Dash detested interstates. He cited them as a final nail in the coffin of the country he loved, the Continental 48. He had a list of bete noires. Interstates, television, chain stores and condo "villages” were at the top. In college, Dash had gotten into a dorm room argument with his roommate about interstates and such.

Seated across from Stu, Dash had said, “It isn't America any longer. We used to have distinct regions. We had New England. And the Deep South. The Midwest. And the West! Unique cultures. Now it's all just a big homogenized mush. Interstates paved the way, so to speak, for this monolithic monotony, aided by television, of course. And, by the by, Alaska and Hawaii are not America. Look at a map. Alaska? That's Canada. Or Russia. Hawaii? Don't make me laugh. It's another planet. No sir! Continental 48 or bust! In fact, I’d like to see the Continental 48 subdivided into four or five, arguably six, regions. Related, loosely confederated, but separate nations, each one with their own national capital. Or, maybe better still: the original 13, all the rest would just be territory, a no man’s land, if you will. Eisenhower! From that fool sprang forth interstates and the 50-state notion!”

Stu did what he usually did before giving his final word. He raised his bearded chin and ran his palm up and down his hairy throat as if pumping a shotgun before the kill. Dash found this to be an odd and obscene habit. Disgusting. “Aw, lighten up! Things are better'n they've ever been, gettin’ better ever’ day. You just enjoy playing the role of Gloomy Gus. Accept reality. All this stuff ya hate? It's provided jobs, good jobs! Life goes on, time marches on. You have no say in how the cookie crumbles. My advice? Go with the flow. Ya can't live in the past.”

"But the past is where life is, all that is good and noble and intelligent. And, dare I say it? All that is sturdy. Read Steinbeck! Read Twain! Read Washington Irving, for crying out loud. Or you can just be an idiot and go to the movies."

Stu chortled smugly, rose, padded to the mini-fridge perched on a card table, grabbed a can of beer–a "frostie" as he referred to them–and then to his room, closed the door. At that moment Dash knew, to the marrow, what it meant to want to murder a man. Dash heard Stu rustling about, heard the beer can opened, a long loud nauseating slurp, then the sound of a needle dropped onto an LP, followed by a strummed folk guitar soon joined by the cloying voice of an absurdly popular singer-songwriter whom Dash couldn’t stomach. The urge to kill rose one entire notch. Preferring discretion to homicide, Dash went for a walk.

There’d been a brunette on campus that Dash fancied, was just getting know in class. One day he spotted her in the student lounge, slouched on a worn sofa, reading a copy of Ms.magazine. Casting a shadow over her, Dash said, “Say, Mary! You’re not a women’s libber are you?”

She looked up. “Why, yes. Yes I am!” Mary Fitzgerald’s mouth was set in defiance. She sat up, shoulders squared, ready for a scrap.

“That’s preposterous! It goes against the laws of God and Mother Nature. Your arms are much too short to box with them! You’re beat before you even enter the ring. Not that I bear a grudge against Mary Shelley, or even her mother. But neither can hold a candle to Jane Austen, for crying out loud. Take a gander at your feminist friends: a slatternly coven. Not to mention treacherous! Solidarity in sisterhood? Don’t make me laugh. No one stabs a gal in the back with greater glee than a gal. Studies have shown this. Not that I need a study to underscore the patently obvious.”

She was fury incarnate glaring up at him. He didn’t mind one iota. She was exquisite in her wrath. Dash noted how lovely her pink lips and green eyes were. No lipstick, no mascara, just an unvarnished fightin’ Irish beauty. These days, too many warpainted women are strutting their stuff like $2 harlots. Cosmetics bury the purely feminine as surely as a mountain mudslide snuffs out some poor hapless village.

Mary Fitzgerald’s angry eyes intoxicated him. Hit with a bolt of inspiration, Dash dropped to one knee and held her right hand. He bowed his head, then looked up, directly into those mesmerizing Emerald Isle eyes and said, “Tell you what! Let’s escape! Far from the madding crowd! Marry me, Mary! We’ll move to a cabin in the woods, have a slew of children, five or six of ‘em! Or more! We’ll grow our own food! You’ll jar vegetables and fruit! And I’ll hunt for our venison, which you can salt. We’ll feast in the winters on what we’ve gathered and grown! Winters! We’ll read our books hearthside, cozy, the kiddies playing board games, the newest one napping in a crib that I’ll craft in my workshop! We’ll live happily ever after!” She withdrew her hand in a shot, stood and fled.

He never saw Mary again, except for a couple of times from across the quad, once in step with Mr. Merrill, a tweedy middle-aged married professor of art history and philosophy. Their shoulders too close for propriety. “Yep,” Dash thought, “a gal is stabbing a gal in the back. With glee. Look at her sunny smile knowing full well that Mrs. Merrill and the two daughters are being set for one precipitous fall. This campus is little more than a sewer.”

After the end of sophomore year, Dash dropped out and opened his shop on the opposite end of town, far from university life, in a struggling blue-collar neighborhood that had once been Gilded Age grand. Victorian behemoths had, largely, been converted into apartments, and the occasional boarding house—if not razed to make way for parking lots for said rentals.

Dash had been older than most of the students. After high school he hitched around the country, working odd jobs for a year, until his draft notice. He served his uniformed stint, attained private first-class, remained Stateside. His was an honorable, if lackluster, discharge. After barracks life, his furnished room seemed royal in its comparative luxury. The humble hovel was his castle.

Wednesday, Dashwood Bryant unlocked the front door to his shop with an unconscious sigh and crumpled the note in the window. The dream dead, he readied for a routine day at work.

Being far from campus meant a large loss of potential foot traffic. But it also meant little of the collegiate riff-raff to contend with, slobs wandering in, wasting his time with inane questions, preening their store-bought knowledge, possibly shoplifting. Lack of business? So what! Let the world work a path to his mandarin mountain only if it truly cares to. His rent was a token $1 per annum, plus utilities, contingent on him handling a host of custodial chores, nothing too backbreaking. The landlord was happy to see the storefront occupied. And a bookstore gave the property an intellectual ambiance, a tasty bait to lure a more upscale renter: young, professional. Greg Maharis had held a moist finger to the wind and foresaw another change to the neighborhood. He placed his bet on it shifting back upscale, albeit in a different way. Give it a decade. Now’s the time to invest, while the market’s low.

Dash had no phone in the shop or his room. Penny saved, penny earned. His telephone was a pay phone, usually in a parking lot. He kept a pocketful of silver and nickel.

The October days swayed between balmy Indian summer and chilly gloom, fluttery wind. Today was one of the latter. Dash watched a hornet in his shop window. It was confused, turning in circles, pausing to attempt to sting the glass. Its season is drawing to a close, and the little guy is not going to go quietly into the night, Dash thought. He pondered whether it was kinder to quickly crush the insect, put it out of its ineffable sorrow, or to let it live, to experience a hornet’s existence to the bitter end. He opted for the latter. It’s all part of the cycle; to intervene would be a sin.

The following day, around noon, in the back of the shop, Dash was squatting over a big brown cardboard box of old cookbooks. He’d been dusting and sorting them when he discovered a volume of Wilbert Snow mixed in. Eagerly he opened it and lost himself in flinty New England. After a spell, his knees, then his thighs, ached. But he was oblivious to the pain. Or, maybe the pain spurred him on, driving Dash deeper into verse? In the distance, he heard the bells jingle over the door. With an effort, he rose, went to the counter to behold the girl of his dreams. Standing there. In calico. With shoes on for once, flats. Everything went fuzzy and fizzy and pink. He felt so very faint. Dash placed both palms on the counter to brace himself.

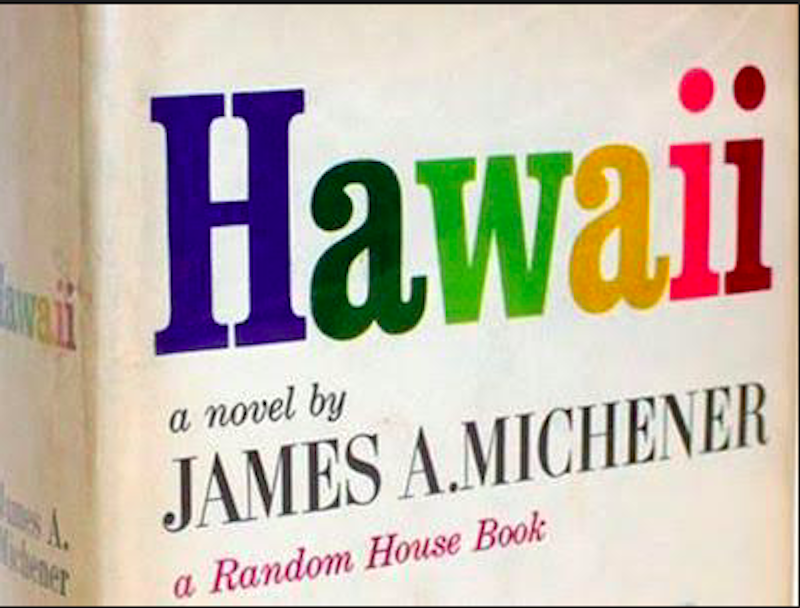

"Hi! I'm looking for a book by James Michener. The title is Hawaii. I've always wanted to go to Hawaii, but that's never gonna happen! Someone told me that his book is the next best thing.” Her head tilted. “Hey! Don't I know you?" Feebly, Dash grasped his chair and sat. He stared at the bare wood floor for a few heartbeats, looked up and croaked, "Yes."