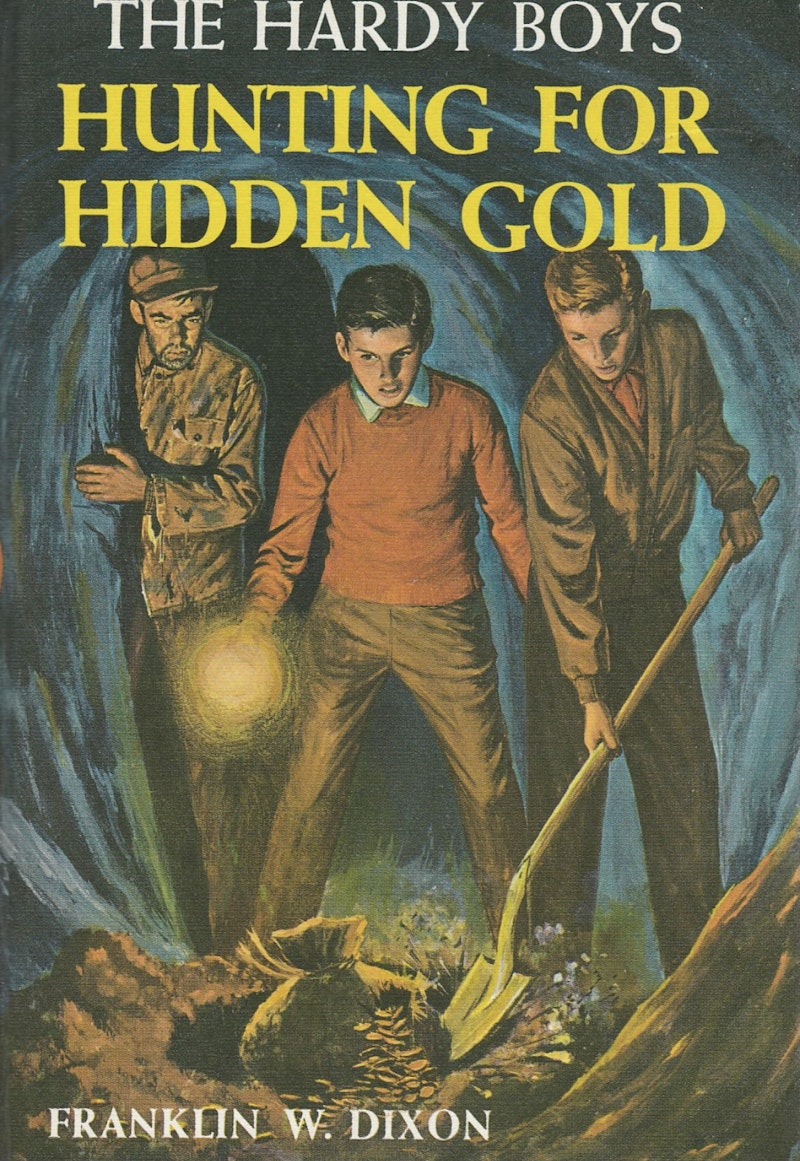

Someone I was talking to recently said that the Hardy Boys books got him into reading as a young boy. That also was my experience. A set of these novels about teenage sleuths, Frank and Joe Hardy, who outfox the grownups in solving crimes, was in my bedroom when I was around 10, and I ripped through them.

I don't recall reading much else that was aimed at young people. The first adult novel I can recall giving me a thrill was Charles Dickens' Great Expectations, which I was assigned to read in English class in seventh grade. Reading that didn't feel like homework. Pip, the young boy who receives a moral education in the story, and the rest of the characters—the convict, Magwitch, who took advantage of Pip, the half-nuts Miss Havisham, and the beautiful but cold Estella—were fascinating, as was the elaborate plot.

The two other books that stood out in my pre-college days—both assigned in English class—were Robert Penn Warren's All The King's Men, a dark, man-ruined-by-the-system story, and Victor Hugo's Les Misérables, the riveting story of Jean Valjean, who was sentenced to 19 years for stealing a loaf of bread and ended up fleeing the law via the sewers of Paris. Warren's tragic Southern drama, a study of individual corruption, remains the best political novel I've read. Hugo's vast imagination was on full display in Les Misérables, and I couldn't put that book down either. The author was critiquing social issues such as lopsided wealth distribution, the justice system, and industrialism, but the "detective story" aspect of the book, which is reflected in the TV series The Fugitive, is what gripped me.

In college, I had "phases" of going through all of the novels of a particular author. The first one was Jack Kerouac, beginning with On The Road. What hooked me was the freedom that Sal Paradise, Dean Moriarty, the other characters enjoyed. How they lived their lives, just roaming around without a care for the normal world, was intoxicating to read about as a teenager, although I'm not sure I'd feel the same way if I read it now. It's possible that my enjoyment of the book was rooted in a sense of longing that I once felt, and re-reading it in a more neutral frame of mind might show me all of its flaws.

Then it was on to John Steinbeck, sparked by a close college friend's ravings about Tortilla Flat, the author's first commercial success. I enjoyed Steinbeck's humorous portrayal of a bunch of hapless drunks and thieves in Monterey, California. The "paisanos" were scoundrels who could occasionally act with nobility, but always showed a joy for life and total lack of ambition. Cannery Row, also set in Monterey, had the same humor and pathos.

Steinbeck's Travels With Charley: In Search of America, a colorful, personal travelogue, is the first travel book I'd ever read. Years later, I'd read an even better book about the guy driving around the U.S. and hanging out with regular people—William Least Heat Moon's The Blue Highway.

The author—along with Hunter S. Thompson and Kerouac—who had the biggest impact on me during the college years was Henry Miller, beginning with Tropic of Cancer and Tropic of Capricorn, both set in Paris in the 1930s. The opening passage sets the tone: "I have no money, no resources, no hopes. I am the happiest man alive. A year ago, six months ago, I thought I was an artist. I no longer think about it. I am. Everything that was literature has fallen from me. There are no more books to be written, thank God."

Miller, who also painted, loved art, but hated the pretensions that often surrounded it, thus his comment on "literature." The author was influenced by Walt Whitman's commitment to living life on your own terms and seeking out random people and experiences. In a sense, Miller's life was his art. After those two novels, I read his entire work, which included a fine travel book, The Colossus of Maroussi, set in Greece. In a nutshell, what attracted me to this author was his endless quest for adventure that came through in his semi-autobiographical novels that combine storytelling with his philosophical musings and social commentary. His Air-Conditioned Nightmare is a scathing critique of the corporate life.

Hunter S. Thompson resembled Henry Miller in a number of ways, including making his life his art and not caring about adhering to societal norms. I read Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail, a brilliant piece of political reporting, and never stopped. Although the quality of his work tailed off later in his career, it never lost its energy.

Thompson was a great satirist and wit. When he got into the zone behind his typewriter, there was nobody like him. Check out his lesser-known "eulogy" to Richard Nixon for one of the funniest, sustained polemics ever written. In it, he justifies his use of "scum" and "rotten," words not found in objective journalism, to describe Nixon: "It was the built-in blind spots of the Objective rules and dogma that allowed Nixon to slither into the White House in the first place. He looked so good on paper that you could almost vote for him sight unseen. He seemed so all-American, so much like Horatio Alger, that he was able to slip through the cracks of Objective Journalism. You had to get Subjective to see Nixon clearly, and the shock of recognition was often painful."

This leads me to Tom Wolfe, a contrarian I associate with Thompson because they were friends (Wolfe said Thompson was “the only twentieth-century equivalent of Mark Twain”) and both used experimental techniques in their writing. The book that put me on my Wolfe kick was Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, in which the prose poet captured the essence the riotous summer of 1964 bus trip across the country by Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters, the successors to the Beats after Kerouac had faded into drunkenness. Wolfe's keen powers of observation and flamboyant prose kept astounding me as I made my way through all of his non-fiction work.

My John Updike phase began with Rabbit Run, the anti-hero story of Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom, a former high-school basketball hotshot who's lost at 26, feeling burdened by a wife and a child who hold him back from all the fun he could be having. Updike cleverly tricks the reader into liking Rabbit in the beginning, and then he slowly reveals character flaws with his masterful prose. I completed the Rabbit quartet—Rabbit Redux, Rabbit Is Rich, and Rabbit At Rest—one of the most in-depth character studies of an individual in literature, and over the years I've gone on to read most of Updike's other books, with only the occasional disappointment such as his 2006 novel, The Terrorist.

A writer I'd never even heard of in college was a revelation when I discovered him—Elmore Leonard. Numbers nine and 10 from the author's Ten Rules of Writing sum up his style: "9. Don't go into great detail describing places and things. 10. Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip."

I'm assuming that the master of economical prose isn't a big fan of Cormac McCarthy, especially his incessant description of desert flora in Blood Meridian, but what Leonard writes, unlike that particular McCarthy novel, is so much fun to read. The "Dickens of Detroit" isn't trying to dazzle you with lovely sentences; all Leonard wants to do is entertain you, and he always succeeds with his stories of lowlife criminals and the lawmen pursuing them. How could anyone resist a book—Mr. Paradise—that starts out like this: "Late afternoon Chloe and Kelly were having cocktails at the Rattlesnake Club, the two seated on the far side of the dining room by themselves: Chloe talking, Kelly listening, Chloe trying to get Kelly to help entertain Anthony Paradiso, an eighty-four-year-old guy who was paying her five thousand a week to be his girlfriend"?

I've left off a bunch of great writers on this list, but I recently got around to reading Louis-Ferdinand Céline's Journey to the End of the Night. My reading history, from the Hardy Boys to Céline, has provided a lot of enjoyment over the years.