I'm not sure how the word “sublime” rings today. Perhaps merely as a general term of praise, an archaic-sounding “awesome.” If I've heard it spoken aloud lately, it was plucked out by some absurdly literate British play-by-play announcer: "a sub-liime goal!"

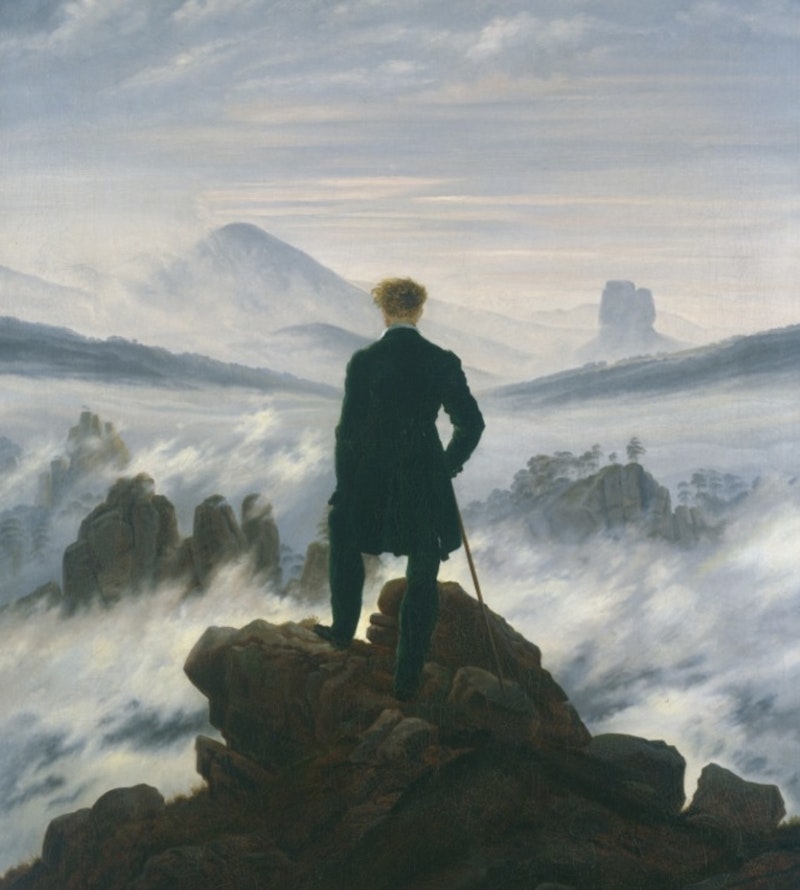

But the word used to have a specific meaning. "The sublime" was traditionally paired with and contrasted with "the beautiful" as the ultimate aesthetic values. Where beauty was associated with pleasure, the sublime was associated with fear: with being astounded, overwhelmed, enveloped, possibly annihilated.

Longinus, in his ancient treatise on the concept, says that a little stream may be beautiful, but the Nile and the Danube are sublime. The clear light of a lamp can be lovely. But it's as nothing compared to the caverns of Mt. Aetna, "from whose raging depths are hurled up stones and whole masses of rock, and torrents sometimes come pouring from earth’s center of pure and living fire." Later writers favored the storm at sea.

The British statesman Edmund Burke wrote one of the best books on aesthetics: A Philosophical Enquiry Into the Sublime and Beautiful (1757). "Whatever is fitted in any sort to excite the ideas of pain and danger," wrote Burke, "that is to say, whatever is in any sort terrible, or is conversant about terrible objects, or operates in a manner analogous to terror, is a source of the sublime; that is, it is productive of the strongest emotion which the mind is capable of feeling." The experience of the sublime is more intense than the experience of beauty, because, he says, pain is more intense than pleasure.

Burke lists aspects of the sublime. It’s powerful. It inspires terror. It’s obscure, amorphous, not fully comprehensible. The sublime suggests vacuity, darkness, solitude, silence, vastness, infinity. It suggests God.

But the sublime is, nonetheless, an aesthetic experience and an experience that we can even seek. Kant, writing some 30 years after Burke, puts it like this: "Nature can be regarded by the aesthetical judgment as might, and consequently as sublime, only so far as it is considered an object of fear. But we can regard an object as fearful, without being afraid of it."

To experience the sublime, you not only have to be overwhelmed and threatened with annihilation; you have to get some distance from that experience and be astonished by what threatens you.

Climate change and many of its apparent effects—typhoons and tornadoes, wasting droughts, vast floods, and huge wildfires—seem sublime. The carbon in the atmosphere is invisible, obscure, gaseously amorphous, its effects spreading over everything yet not localized to a single source but erupting in disaster suddenly here or there. And if we’re not right in the midst of a disaster, we’re likely experiencing these things at a distance: on our screens, really. Perhaps we alternate between terror and helplessness in the face of this force. That's about as sublime as it gets, an awe-inspiring spectacle.

Any one of us is helpless in this regard, except possibly as part of a much wider social movement which we also can't control. I can buy an electric car, but I can't make a significant dent in our carbon. The force is vastly beyond my power. But experiencing it aesthetically on exactly that basis, turning hopelessness into sublimity, encourages passivity: just enjoy how cool things look as they go out of existence.

That, I admit, sounds wrong. It may strike a climate-change activist, or anyone who feels urgently that we must mobilize to do everything we can about the situation, that taking an aesthetic distance from climate change and its effects, quasi-enjoying the apocalypse, calling it like a play-by-play man, is a sign of privilege, soon to end, and a completely irresponsible attitude.

But if I experience the changes to earth's atmosphere aesthetically, that doesn't necessarily mean that I can't try to do something about it. Burke, Kant & co. expected us to waver at the volcano, experiencing it as sublime between bouts of fleeing, pulling back momentarily, full of wonder as well as horror. And though we may be taking action to try to fend off a disastrous future, we’re also alive right now, in a way that has meaning and intrinsic value, or does if we can experience it consciously. Even in 2021 we don't have to live entirely without contemplation: our vulnerability, our mortality as a species, is an occasion for that. That might lend our lives value right now; it might be urgent, in a way. We might not get a lot more chances.

"The anthropocene" as a sublime development, however, has certain distinct features as an aesthetic object. This isn't God (I think), it's not Aetna. It's a storm at sea, but it's one that we whipped up ourselves. Longinus starts by contrasting sublime things with things human beings make. We’re capable ofmaking all sorts of sublime effects, from nuclear war to mountaintop removal, to profoundly altering the atmosphere. You might think that this would disqualify these things as sublime, because human things are supposed to be comprehensible to humans, because human things are not obscure to us.

But they are. If climate change shows nothing else, it shows that we’re unknown to ourselves. All this time, since we harnessed fire and started burning things, we’ve been unaware of what we were doing. I suspect this will always be the case, for as long as we last: we don't know most of what we’re doing, or even why. We might not have a clear idea of what we want. We definitely don’t have a clear idea of who we are. That’s the very form of tragedy, the sublime art par excellence.

That we, not the gods or Satan or Nature, are the force that is destroying us, forms a peculiar circular sublimity. We're powerful, and we’re not comprehensible. That doesn't mean we’re like God, however. God is incomprehensible to us, but (presumably) completely comprehensible to himself. But we are a god who's in the midst of a perpetual emotional crisis, a god who needs therapy, a god who’s unknown to himself. However, we couldn't become known to ourselves without becoming something completely different than we are. It's not going to happen, people, because then we wouldn't be people.

Maybe it's absurd to say that we're getting what we deserve, since we did all this by accident. But we’re getting what we are, a constant surprise to creatures like us, and we’re getting it good and hard. On some days, I feel the comedy rather than the sublimity: we’re the species that must trip on itself, the cosmic pratfall. But that's when I start getting worried morally about what I’m becoming. That's when I'm in danger of losing track of the fact that people are suffering, and that we’re all endangered by us.

In any case, if this is sublime, it's a different sort of sublime, arising not from the obscurity of the volcanic cloud or the incomprehensibility of infinity but out of the essence of ourselves, our peculiar combination of ignorance and arrogance: the sublime spectacle of a self-devouring machine. Lord knows what the sublime Kant or beautiful Burke might make of that if they were around now, but it might keep them writing treatises on aesthetics right up to the end.

—Follow Crispin Sartwell on Twitter: @CrispinSartwell