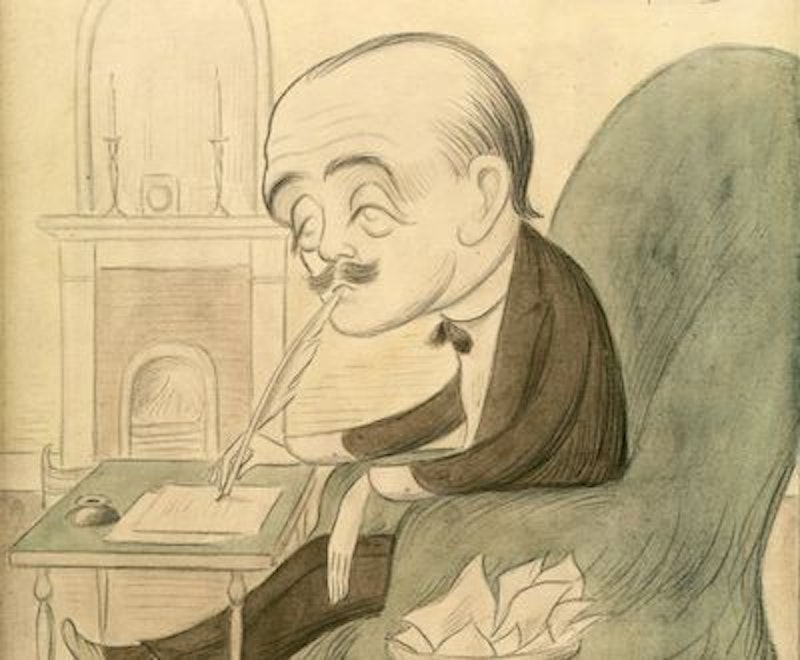

Max Beerbohm was quite clear about the look in George V’s eyes, “the eyes that showed so tragically much of effort, of the will to please—the will to impress,” and so on. He wrote all this in a letter to his wife after he saw “the little King” preside at the opening of Parliament in 1914. Odd, because Max drew a cartoon of George at this event, and the eyes do not exhibit any will, let alone a will to please or impress because of his role. Perhaps the cartoon George resents his royal trap, or perhaps he’s hopeless and waiting out existence. But he isn’t living up to anything. His shrimp spine wilts. His poached eyes, which show nothing, occupy a crevice beneath the immense busby hat that somebody lifted atop his skull. The poor mite has been wrapped in military regalia and slung onto a horse, and this is what life has ahead of him.

That’s not quite the outlook Max describes in his letter. But perhaps Max felt a few different things. He used to argue that a name’s sound had no effect in itself, this man who created the name Naomi Greckle. He said caricature just made big noses bigger and revealed nothing about personality. But he drew Edward VII like a curse word, a miniature icon of ignorant selfishness and hapless bad temper. When Max drew Edward’s son, he meant something or other, and I figure that something was the experience of being squashed. The cartoon may be the only royal portrait in which everything else looks like it’s going to fall atop the monarch.

Physically they couldn’t. His giant horse, for example, is right under him. The busby might fall off him but not on him, and the line of august buildings in the far background is safely remote, as are the soldiers assembled in an endless, busily contoured line in front of the buildings. The blankness of the parade ground could fall on nobody, since it’s underfoot. Even so the visual collision of these entities—the giant hat’s looming, blatant horizontal versus the three heavyweights running vertical, with the parade ground’s blankness battling all—creates a page that visually falls in on itself. Seated front and center in the picture, the poor King is positioned where the design caves. Instead of popping out at us, he pops in. The eye still looks for the picture’s center, but it has to fight a bit to do so, bat away horse’s mane and the majestic buildings and the serried, miniature, military row and the blankness, and really arrive on that divot of a face. The build-up to the punchline is extended and the punchline magnified. At the center of all that cluttered importance is this dispirited scrap of a man.

A cartoonist who had to work for a living probably couldn’t afford this visual trick. To get in the way of the reader’s eye, even for a little bit, is to get in the way of landing a job. But Max had almost enough money to be a gentleman of leisure and he amused himself. That man who was a now forgotten thing, a belle-lettrist, drew his picture of a now forgotten king. He got him dead to rights.