In 1928 the New York State Education Department devised an initiative to mark places of historical significance, and over the next four decades, almost 2800 markers were placed all over the state. The signs themselves are marvels of design. Most feature dark blue backgrounds with gold raised block lettering and trim, though there are variations in color, lettering, and very occasionally shape. The state discontinued the series in 1966 after high-speed travel on expressways became the norm.

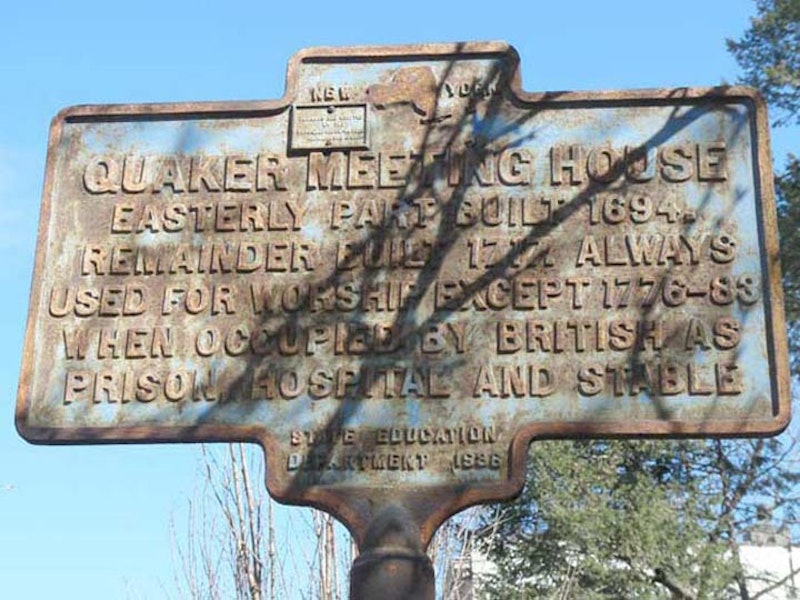

This surviving historical marker is found at the 1694 Flushing Quaker Meeting House at Northern Blvd. and Linden Pl. It’s in the worst shape of all the remaining markers. Oddly, the John Bowne House around the corner on Bowne St., which was built in 1662, didn’t rate a marker.

The Friends Meeting House has been used for Quaker religious services since it was constructed, a span of over 300 years. Not only is the building remarkable for its age, it also figured in one of the first shots fired in the war for religious and personal freedom that’s still fought today.

In 1657, the Dutch were still in charge of New Netherland, and Governor Peter Stuyvesant ruled with an intolerant hand. He forbade any religion but the Dutch Reformed Church of his homeland, even for the English settlers who were starting to trickle in. Quaker settlers sent a letter to Stuyvesant in that year that is known as the Flushing Remonstrance, reiterating the settlers’ desire for religious freedom. The document was signed by Flushing’s town clerk and sheriff, who were not Quakers. Nonetheless, they were soon tossed into prison, and then summarily fired.

Thirty-seven years after the Flushing Remonstrance was presented to Stuyvesant, this meetinghouse was raised in 1694. At the rear you’ll find a quiet churchyard with graves hundreds of years old. More old stones can be found at St. George Church at Main St. and 37th Ave.; that church, where Francis Lewis of Declaration-signing and Queens Blvd. fame was a vestryman, dates to 1854.

Prospect Cemetery in Jamaica claims one of Queens’ four surviving NYS historical markers, on 159th St. between Archer and Liberty Aves. In poor shape just a few years ago, it has been spiffed up as part of the overall campaign to restore the formerly forlorn burial ground.

Prospect Cemetery, entered from 159th St. south of Archer Ave. and the Long Island Rail Road overpass, is probably the oldest cemetery in Queens, and perhaps the entire city. Old records show that it dates to the 1660s. The cemetery has 53 Revolutionary War veterans, 43 Civil War veterans, three Spanish-American War veterans, and many interments of prominent Long Island families such as the Lefferts. Prospect was designated as a city landmark in 1977.

In recent years, the Prospect Cemetery Association has cleaned up the weeds and other accumulated debris that had choked the old burying ground for decades. In addition, funds were acquired for the reconstruction of the cemetery’s Chapel of the Sisters, built by Nicolas Ludlum as a memorial to his three deceased daughters. New doors, windows, floors, and stained glass windows were installed as well as new heating, plumbing and electrical systems.

The chapel is now known as the Illinois Jacquet Performance Space (named for the famed saxophonist, a Louisiana native who moved to NYC in 1946 and lived in southern Queens for many years before his death in 2004).

At Park Lane South and 85th St. in Woodhaven we find a well-preserved NYS historic sign standing on private property.

The sign marks the first address in Queens to be renumbered under the “Philadelphia plan,” which re-numbered most of Queens’ streets, with lower numbers at the East River that rise as you proceed east and south. Many years ago, when Queens was a collection of small towns divided by acres of farms and fields, every town had its own street naming and numbering system. This worked when Queens (then also comprising what is now Nassau County) was a separate and self-governing county.

Once Queens consolidated with New York City and became slowly urbanized, this didn’t stand, as a plethora of Washington Streets, Main Streets, and 1st and 2nd Streets found themselves in the same street directory in the city ledgers. The Queens Topographical Bureau, under the guidance of C. U. Powell, unified Queens’ street system in the 1910s. They assigned a number to almost every street in Queens, except those in historic areas such as Flushing; some existing major roads kept their names, but were assigned the honorific Boulevard or Parkway to replace what was a mere Avenue or Road. The Jackson Avenue-Broadway combination was renamed Northern Blvd., for example, while Little Neck Rd. became Little Neck Parkway. Numbered Avenues, Roads, Drives and Courts run east-west, while Streets, Places, Lanes and Terraces run north-south. Streets run from 1 to 271, and Avenues from 2 to 165: why Queens doesn’t have a 1st Ave. is a mystery.

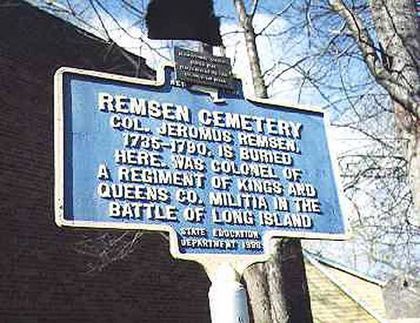

Another surviving NYS historical marker is at the tiny Remsen Cemetery at Yellowstone and Woodhaven Blvds. It’s one of a handful of surviving family burial plots scattered around the borough; among them are two belonging to the Lawrence family in Astoria and Bayside. More are buried beneath architecture and parkland; some, like the Wyckoff-Snediker Cemetery in Woodhaven, are on church property and are not visible from the street.

The Hempstead Swamp once occupied a vast area of land just east of present-day St. John’s Cemetery in Queens. The greater area was first settled in 1653 as “Whitepot” by English and Dutch farmers, including the Remsen, Furman, Springsteen and Morrell families. They found the land good for growing hay, straw, rye, corn, oats and various vegetables. During colonial times, there were only a few roads that cut through the marsh. One of these was Whitepot Rd., known as Yellowstone Blvd. today. The other was Remsen’s Lane, a road that became 63rd Dr. and 64th Rd. The Remsen family lived along the road, and their burial ground, which includes the resting place of Revolutionary War veteran Colonel Jacobus Remsen, is still intact here.

—Kevin Walsh is the webmaster of the award-winning website Forgotten NY, and the author of the books Forgotten New York (HarperCollins, 2006) and also, with the Greater Astoria Historical Society, Forgotten Queens (Arcadia, 2013)