Just below Warren Publications’ gory/sexually explicit chillers, the drugged out European fantasies of Heavy Metal, and Myron Fass’ perverse comic magazines. Behind the sinuous/clean cut/PG-rated super heroes and do-gooders of Marvel and DC. Just above the family-friendly product of Whitman and Archie. Throughout the 1970s and 80s that’s usually where you’d find a selection of Charlton brand comic books at the rack at your local grocer, newsstand, convenience store, smoke shop, gift shop, or discount department store. Much of Charlton’s output was too unconventional and morally oblique for standard super hero fans, too mature and scary for the little kids, and not violent or graphic enough to compete with the visceral/uncensored thrills offered by magazine comics.

Charlton had its own niche and commanded a devoted cult following. They specialized in making comics for people who needed something other than genre predictability, avant-garde confrontation, or any of the other polarized aesthetics of the 1970s and 80s. During its first 30 years in the business the publisher’s talent roster had scores of big name creators and just as many visionary obscuros and one-shot artists who rarely worked for anyone else. Across the board, the company’s freelance contributors turned out powerful work simply because Charlton gave them a level of creative freedom unmatched by any mainstream competitor.

While Charlton’s comic book line was eccentric, the company’s business model stayed conventional for most of its 50+ year existence. Crossword puzzles, coloring books, paperbacks (released via their Monarch subsidiary), Hit Parader, Song Hits, other pop music periodicals, and the first two issues of hardcore porn mag Hustler all provided the bread and butter for their operation. Charlton’s printing, manufacturing, promotion, and distribution were done in-house; content licensing agreements with overseas markets also brought in steady profits. Publisher John Santangelo Sr. and disbarred attorney Ed Levy were the reformed criminals in charge when Charlton began in 1946 shortly after the duo became friends while stuck in prison together. Santangelo’s sentence came about due to copyright violations he made while working with a different publisher; Levy’s incarceration was a result of a political scandal. Once out of the slammer they set up shop in Derby, Connecticut. Initially Charlton's comic line quietly followed industry trends to the letter.

All that changed in the late-1960s. The company’s output then mutated into a new beast with the hiring of editor George Wildman. As an ex-ad man, Wildman had the combo of an artist’s eye for graphic design and a businessman’s marketing instincts. His guidance eliminated a ton of the financial risk that could’ve plagued Charlton as its comics line developed an anomalous trippy signature style, a style brought to life thanks in part to Wildman’s unique editorial vision.

In the 1970s a paper shortage caused a brief shutdown. At the same time, expenses related to the cost of maintaining their mammoth ancient printing presses hit hard. By the late-70s they were running so low on money they couldn’t pay contributors. With a backlog of unpublished stories, Charlton’s comics continued to feature all new material through 1978.

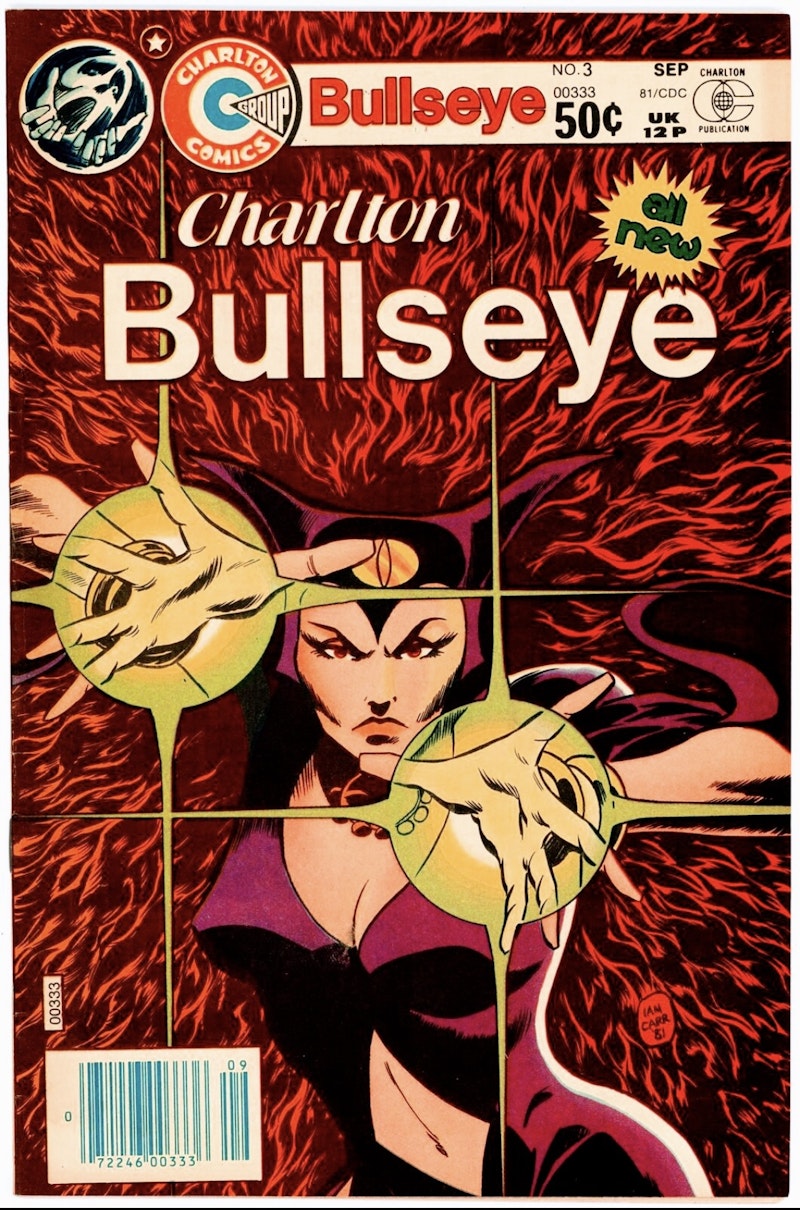

In 1981 Charlton made a brief comeback just as the direct sale market and mainstream fan culture began transforming the comic book industry into a global socio-economic phenomena. The outsider-imprint then took a detour down a path where only one other major competitor dared to tread. DC Comics’ "Dial H For Hero" had success thanks to its innovation and novelty as a feature that starred offbeat characters developed by amateur artists. These were then assimilated into “Dial H” stories and illustration made by pro-level DC creators. Charlton bested DC with Charlton Bullseye, a series completely comprised of material by unpaid amateur contributors.

There was nothing new about comics created by inexperienced unknowns, but the concept of a veteran publisher giving a national platform exclusively to amateurs was unprecedented. Themes that previously had been the provenance of obscure small press/indie comics were turning the spinner rack at local stores into a whirlwind of pop art damaged hallucinations. Failed newspaper strips, cult fanzine characters, and the barely coherent scribblings of teen Jack Kirby wannabes were suddenly rubbing shoulders with Power Man, Spider Woman, Superman, Green Lantern, Walt Disney characters, Star Wars comics, GI Joe, and all of the other four-color fantasy icons. Charlton Bullseye was a portal into a new dimension, a place where nothing could separate the mainstream from the fringe.