I’ve been a lifelong supporter of every woman’s right to safe, legal abortion and contraception. That may seem a strange conviction to hold from a young age, but I heard the topic discussed often in my home.

Because I’m a male supporter of reproductive rights, along with many other “liberal” ideas, others sometimes assume that I ground that support in the conventional litanies of contemporary American progressivism. As those articles of faith are deemed sufficient justification in themselves, there’s no need to confirm my reasoning. For me to more than discreetly cheerlead for those more qualified to speak to a woman’s right to choice is often, I’ve discovered, in bad taste.

It was my father who insisted upon speaking with his two sons about abortion and birth control as matters of political and social importance. He’d travelled from Western Europe through the Mediterranean, the Middle East, and Russia, to India, Central Asia, and elsewhere in the 1960s. Fresh from the Army, he traveled very cheap, often without American companions. He kept an open mind.

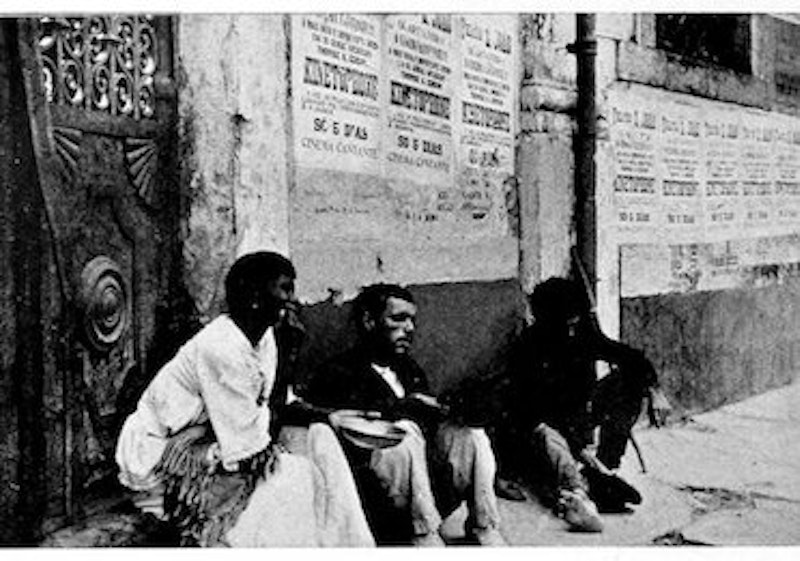

When my brother and I were young my father transported us with stories of exotic and beautiful places and fascinating, unforgettable people, but he also spoke of the suffering he saw. My father was a keen amateur photographer, and he documented his travels in pictures. One such picture hangs in a tiny bathroom under a staircase in my parents’ home. It’s a very odd choice for a decoration. The close-up photograph shows a common municipal sign announcing an ordinance by a riverbank. I remember it hanging there when I didn’t understand all the words, or the reason for this specific prohibition. Alongside the English, the warning was repeated in another three languages, written in alphabets I didn’t recognize.

The sign reads, “The taking of photography of beggars, lepers, and dead bodies is strictly prohibited.”

My father had many arguments supporting the right to and need for safe and legal abortion and contraception, but the one that struck me most immediately was the argument from needless human misery implicit in this sign. I continue to feel that way. At my dinner table, plenty of food in front of me, we’d discuss overpopulation, poverty, and the dignity of life. We considered and discussed whether the world might not improve for all, but especially the poor, if the causes of cyclic suffering could be limited, and how governments could lead or support efforts to do so. Having observed endemic human misery myself, I still believe that unchecked demand for limited resources enforces conditions resulting in the suffering, exploitation, and degradation of many. Obviously larger institutional problems require solving before this systemic state will change, but desire for that change needn’t subordinate concern for the individuals directly affected, in various and ongoing ways, by the laws and policies governing reproduction.

This may seem a rather cold-hearted (it’s obviously incomplete) view of social problems, but, unlike the argument contra the patriarchy, it’s rooted in a pragmatic social and economic idea: government should not oppose the sensible limitation of the material needs placed upon mothers, families, the community, nation, and world. Morally, it rests upon the view that human potential, in order to flourish, requires a measure of dignity, autonomy, and opportunity.

The lessons learned in my youth are not invalidated by the distance in time, space, culture, and privilege between the lepers and me. I can’t fully understand the conditions of a child or a mother in such a place. Should my father then have neglected to pass on these lessons? To pass on such experiences and reflections is the goal of any ethical education, and I thank my father for it.

Starting from similar principles or from principles fundamentally different or opposed to mine, one might reach radically different conclusions. Much more would need to be said on both sides to arbitrate the dispute, and I’m prepared to be wrong. I bring up this politically sensitive issue merely to provide an example of the assumed forfeiture of moral authority implicit in my endorsement of a particular political position. If I ground my support for women’s reproductive rights exclusively in my support for women’s struggle for liberation, I can be right, but only through sympathy with a victim whose conditions I shall never experience. Because I’m a man, my rights can never be threatened. I can control my own body.

Here I must point out that the government doesn’t regulate the bodies of women alone. The government may take my life through capital punishment, but deems my ailing grandmother’s suffering theirs to demand and prolong.

According to the dogmas of the cannibal left, only a woman’s right to the control of her own body is under threat, and I can only sympathize, not suffer. Only this injustice can grant those who suffer it the proper basis to evaluate the merits of the legal and ethical alternatives at stake. My political beliefs have been reduced to a kind of luxury tourism, providing titillation from the safety of my privilege.

I have independent and sufficient basis for my views, grounded in my own moral judgment and relevant experience. Yet so far from opposing the idea that women should control their bodies, I feel that only a woman, and certainly no abstraction like a government, can possibly weigh the moral significance of her decisions. My view parallels that I hold with regard to end-of-life care and euthanasia.

Without withdrawing my sympathy, I dispute the idea that I can’t derive valid political principles through reflection and reason, or that I’m required to base my political principles upon the logical, ethical, and rhetorical framework of the mainstream progressive left. More importantly, I reject any suggestion that my attitudes toward reproductive rights bind me to other political beliefs.

The reduction of what’s essentially a question of autonomy (like assisted suicide) to one of gender greatly diminishes the force and persuasiveness of the case for reproductive rights. Though I do endorse the premises and conclusions of the argument I’m assumed to rely upon in my reasoning, it’s not principally why I feel as I do.

To be fair, most progressives aren’t actually hostile to alternative justifications for their beliefs. A minority fears the co-option of their grievances so intensely as to reject the votes of those they intellectually and socially contemn.

Still, the ideological air on the left is stale, offering comfort chiefly to those who huddle together within the consensus, warmed by the bright flames of the culture wars. This demand for conformity is intellectually disgusting. It’s also one of the most frequent accusations against progressives today.

As my moral authority is stripped from me by committee, so too is my incentive to think for myself. The United States today is full of intelligent individuals forced to swallow their pride as they’re absorbed into the caste system of the contemporary left. Progressives by definition desire to improve society through change, yet progressive leaders today actively thwart their own electoral interests and intellectual credibility by their determination to defend their ideals from the refuge of their resentments. The vanity of these exercises betrays the fact that these ideological torch bearers will sacrifice actual social progress to the futile but public exorcism of our country’s many demons.