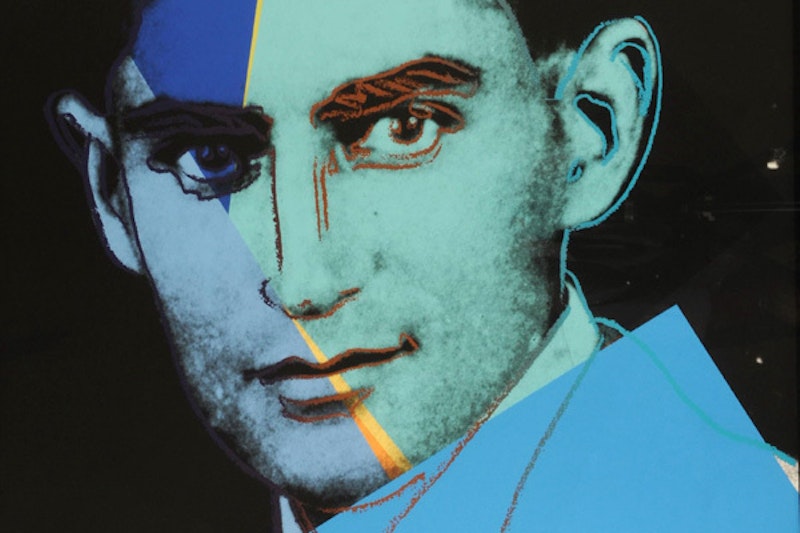

I’m going through a Kafka phase right now because I’m a pretentious college student. Don’t worry: this isn’t an academic examination of “The Hunger Artist” or an analysis of The Trial through a feminist lens. The cliché remains true: everything’s already been said about Kafka, his twisted brand of magical realism, how the only thing more tragic than his fiction was his reality.

I was first assigned The Metamorphosis in eighth grade. Our teacher was a bozo—she handed out colored pencils and crayons after we finished the first section of the book and asked us to visually interpret what we read—so she was no help in comprehending the text. It didn’t really matter. John Keating could’ve been our teacher and it wouldn’t have made a difference. Fourteen-year-olds won’t be able, and have no desire to, understand The Metamorphosis.

I had no intention of ever revisiting the novella until my high school English teacher texted me her intentions of adding it to the syllabus for The Short Novel, a class I helped design in my senior year. I responded with a firm “no way,” recounting my distaste for the book, how it’s just about a dude who gets turned into a cockroach or something (Mrs. Lawrence never required us to finish it). Might as well just show them The Fly and be done with it.

“Just read the damn book,” she replied. “If you really don’t like it, I won’t teach it.”

And so I walked to the nearest bookstore and bought The Metamorphosis, determined to find a glaring weakness in the prose, evidence of the book being more genre fiction than literature. And if I couldn’t manage that, I’d be satisfied with a few nitpicky comments. But of course, inevitably, I only found admiration.

I texted Dr. Beth right away: “I concede defeat. Kafka is dope.”

Novels taught in classrooms are usually despised. No 16-year-old is keen on reading Henry James, especially in 30-page-a-night chunks (The only book that survives this disdain, perhaps, is Catcher in the Rye). Reexamination of those books you hated as teenagers, though, often leads to appreciation (Except for The Scarlet Letter). At the very least, it lends a new perspective.

This reminds me of Mr. Van, my 10th grade trimester English teacher. He was old and crabby and carried a sense of ownership of the school that, in his mind at least, allowed him to teach whatever books he wanted. The perfect disposition for an English teacher. Our syllabus was varied: one Larry McMurtry novel, a Lionel Trilling short story, some beach read from the 1960s called Red Sky at Morning, and, most curiously, A Separate Peace, another book I’d previously read in eighth grade (except this one is better suited for 14-year-olds).

At first the novel played out as I remembered it: two prep schoolers are best buddies, one gets jealous and pushes the other out of a tree, copes with the guilt, and forces the reader to confront issues of moral ambiguity and maturation. Boring. I didn’t even bother opening the book until my friend Zach dared me to focus my chapter six presentation on how “Finny and Gene are totally gay for each other.” Of course I accepted the challenge. It was surprisingly easy to fulfill. I took the novel at face value in eighth grade, but as a high school senior, all I could see was the subtext, the blatant homoerotic subtext. I even wrote my term paper on the subject.

So now, as I read through every tortured word in Kafka’s collected works, I’m reminded that 14-year-olds have bad taste, and I’ve probably dismissed many great books that were simply guilty of canonization. I still don’t plan on reading Henry James any time soon.