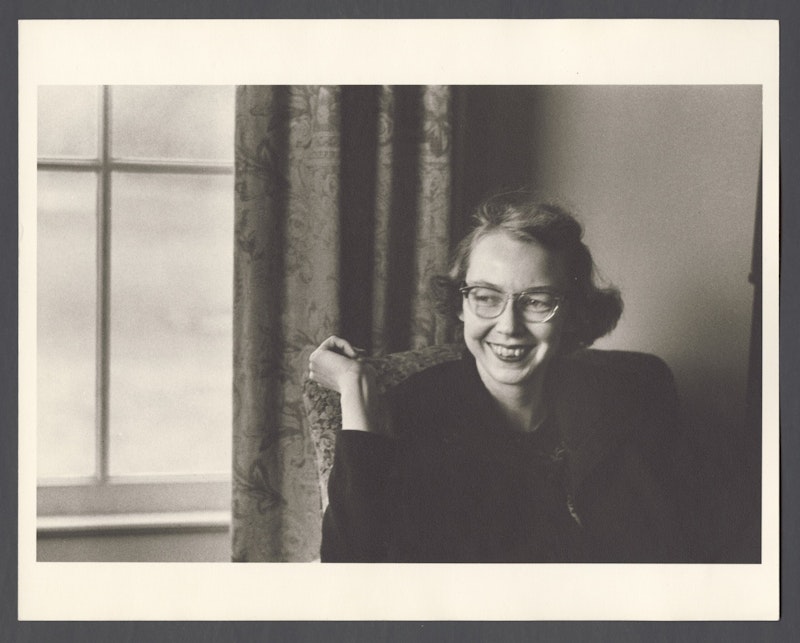

Flannery O’Connor (1925-1964) has been the subject of both love and hate, but one thing that everyone can agree on is that her life and work are intriguing, fascinating, and never-ending fodder for further exploration of both O’Connor and America. A new documentary simply titled Flannery (directed by Mark Bosco, S.J. ry and Elizabeth Coffman) takes a look at O’Connor’s difficult life. (It is part of PBS’ American Masters series and currently available online.)

The documentary features a wide variety of interviews. From O’Connor scholar Ralph Wood to biographer, Brad Gooch, writers such as Alive Walker, Mary Karr, and Hilton Als, life-long friend, Sally Fitzgerald, and fans like Conan O’Brien, Tommy Lee Jones, Brad Dourif and film producer Michael Fitzgerald who made a film adaptation of O’Connor’s novel, Wise Blood. Flannery also contains some never-before-seen footage of home videos. Mary Steenburgen serves as a voice of O’Connor through her voluminous letters she wrote, as well as reading of excerpts from O’Connor’s stories.

O’Connor was a Catholic in the South, which was considered odd. After she graduated from Georgia Tech College for Women, O’Connor was in the prime of her life. She made contacts in New York and left Milledgeville, Georgia. She got accepted into the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and spent some time at Yaddo colony for writers. Her Southern self was exposed to the Northern others, and in many ways, this was good for O’Connor.

New York’s griminess didn’t agree with her, and her friend Sally Fitzgerald invited O’Connor to spend time with her and family in Connecticut. O’Connor gladly accepted and had a newfound freedom to work. But then, she started to feel symptoms of what she thought might be arthritis. Her condition worsened and she realized that had to go back to Georgia to live with her mother on the family farm known as Andalusia.

O’Connor couldn’t grasp how arthritis made her feel so drained until Fitzgerald broke the silence that O’Connor’s mother Regina kept. O’Connor didn’t have arthritis. She had lupus. O’Connor took the news as bravely as she could because she knew it’d be a death sentence. Her father died rather young from lupus and this awful disease for which there was no cure or proper treatment at the time, always loomed on the family horizon. Yet it was also this revelation that set O’Connor free and her return to Georgia signifies the return to roots that manifested themselves in the brilliant short stories she crafted.

Although O’Connor died when she was only 39, she has left an amazing amount of work precisely because she was confined to the farm. She barely left the house except to go to daily mass, and to take care of many peacocks on the farm. Flannery details all of the facts already known about O’Connor, and uses several lenses and points of view in order to illuminate her life and work.

O’Connor’s Catholicism was one of the main themes of her work, which always featured a contradiction and a relationship between violence and grace. In the documentary, Tommy Lee Jones offers some of the best descriptions of O’Connor: “a wolf in grandma’s clothes,” and that O’Connor was “more American than Irish and more Southern than American.” This precisely describes the tension between the North and South, especially at that time.

The reality of institutional racism in the South can’t and shouldn’t be avoided. O’Connor fought the strange biases that were imparted to her by the culture she grew up in. Most of the interviewees have something interesting to offer but by far, it is Hilton Als that stands out. Unfortunately, we’ve turned into a society that uses race either as an ideological tool or to speak about past instances of racism in a clichéd way. But Als ignores that and gives a superb analysis of an instance when O’Connor refused to meet with James Baldwin.

During the Civil Rights movement, Baldwin was travelling to Georgia and O’Connor received an invitation to meet with him. O’Connor responded that she’d gladly meet with Baldwin in New York but that such a meeting was a complete impossibility in Georgia. You could conclude that this is a plain racist statement. But Als has a different take. If O’Connor met with Baldwin in Georgia, the very act would represent a support of Civil Rights Movement and without a doubt, it would’ve been a purely political statement. Als argues that O’Connor was in many ways a reporter, albeit of a literary kind, of the South who was firmly grounded in the culture but also was an outsider. If she’d met with Baldwin in Georgia, her role and power as a writer would have be gone because she wouldn’t have the observational access to the Southern culture.

Als’ thoughts are some of the most nuanced arguments on O’Connor and racism available. He by no means denies the reality of what happened to blacks in the South. However, by offering a deeper analysis that goes beyond clichéd and mushy versions of good and evil, Als invites the viewer to think more critically about not only O’Connor but America’s past and present.

It’s not easy to make a documentary about a writer and directorial choices must be made. PBS’ American Masters series usually serves as an excellent introduction into the lives of noteworthy Americans. In this sense, Flannery has succeeded. At the same time, the documentary would’ve benefited from a longer discussion from critics like Als.

Another significant aspect of O’Connor’s life and work (which are inevitably intertwined) is her Catholic faith. It’s understood that this documentary is not made for the Catholic audience, which is one of its positives. However, the viewers (especially those interested in reading more of O’Connor) would’ve learned more about theological aspects of grace in Catholicism, and the inextricable relationship between suffering and freedom in Christ. O’Connor certainly felt this, especially throughout her illness. One of the most poignant aspects of the documentary is the revelation that O’Connor’s mother marked on the wall calendar the day O’Connor died. She wrote: “death comes for Flannery.” That alone is a theological statement worth exploring.

O’Connor never wrote anything mushy or weak, and her faith was tough and highly unpleasant. But then again, as she always argued, there’s nothing “nice” or “pleasant” about Crucifixion.

How does one reconcile joy and suffering? There are “freaks” everywhere but who is a freak? Can we live harmoniously and peacefully? These are the questions that O’Connor grappled with, and just like her faith, the answers are never easy. The tensions are never resolved, and the uneasy relationship between violence and grace remains.