The line around the block was made up of little peg men who’d been brought there by their wives and left to fend for themselves. None of the voting booths were ready yet and no other building was open nearby. That morning was cold—November 6—and the peg men weren’t prepared. They wore trousers without long underwear, hats with no brims, and mustaches that demanded reconsideration. The wind whipped through the otherwise empty avenue and kept those brimless hats accompanied by ungloved hands.

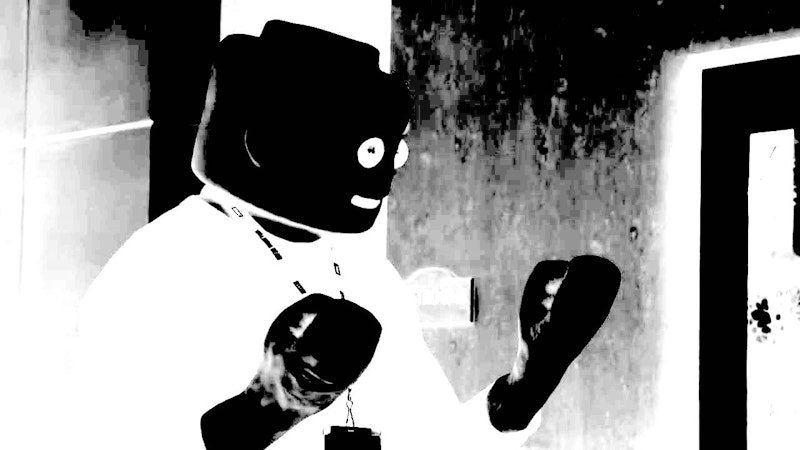

It was more contact than any of them had had with their wives in months, maybe years: these peg men were hen-pecked. Hence the expression, “peg men.” It doesn’t refer to any specific gender, race, or nationality—anyone can be a peg man. One becomes peg when allowing others to make them small. They shrink and grow rounder and balder and calm, if not docile. They don’t mind much because they gave up acting ages ago. Their wives tell them what to do. And these peg men knew that the only thing they had to do that day was vote for Dwight D. Eisenhower. And they did. And the American century was sealed.

•••

Love’s not a game. I’ve been told many times over the years as a narrator, an author of life, that I must enjoy going to parties and other social functions where I may “observe” and “take from life” for my stories, my fictions. The thought disgusts me to the point of nausea. I’m not a life drawing student. I’m not a traditional artist. I’m not an easy creature. I’m not predictable. I’m unreliable. I’m remorseful and courageous. I come from the heart and die by the sword of public opinion, which has never been kind to me.

I’m remorseful and courageous. I’m always a stone.

•••

The peg men entered the library and shuffled in nice and quiet, dusting the debris off their jackets and nodding politely to the kind women working the door. None of them talk; much less make small conversation. Other cultures may have mistaken them for eunuchs, but these peg men were very much sexually active, just not physically. Elderly people, the disabled, they have erotic lives entirely of their own. It’s not something that has to be physical. But I’ve never known any other kind of love, because an embrace is safety. An embrace is what you never had. An embrace is what you’ve always been looking for.

The peg men made noises with their bodies—lips smacking, bellies rumbling, gas leaking—and they shuffled as easily out as they did in, snaking all day in verbal silence as their gray, aging bodies spoke for them. I watched from above as the tears fell upon my collar—it was the last night I saw Charlotte alive.

I didn’t know she’d bought a car—I didn’t even know she wanted to drive. I should’ve taken the keys from her and kept her inside before she could be “un-domesticated.” My wife of three weeks was raped and murdered in our apartment on that cold November day in 1956 because I was busy volunteering at the library making sure that democracy didn’t die in darkness. That may be a contemporary expression, but I believed it at the time. I haven’t felt anything since I found Charlotte’s body, what was left of it: feathers and engine oil everywhere. Apparently she answered a classified ad. She paid with her life.

•••

Three months later I was ready to leave the house. I decided to have a drink at 20, the biggest bar in Schaumburg. I still wasn’t used to it, the silence: how it felt waking up to the flat Illinois sunrise, realizing every day that my soulmate was dead and gone. I got up that day, some time in early 1957 it must’ve been, and wandered the empty avenues, as I did in the three years that followed Charlotte’s murder. I don’t remembered how I ended up at 20 but I remember deciding to go there, knowing that something had changed.

For the first time in weeks I had a resting heart rate that doctors would only call “mildly alarming.” I thought maybe sleep was a possibility.

And then I saw her feathers.

I saw her feathers on the floor of the bar.

Someone walked up to me. "You're named Clem," he said, "and you've come to collect." Say no more: he was dead before he hit the ground. For the rest of the occupants of 20 (the biggest bar in Schaumburg), I cannot say the same. Death took a long time coming for them. But Mr. The Man You May Know As The Man That Accused Me Of Being Named Clem was dead as soon as my spur claw entered his femoral artery and my quills (extracted) went into his eyes and directly into his brain tissue. I hope he got stuck in a consciousness loop that made his death last an eternity. I don't like being disrespected.

That's why I went monkeymode on the rest of the bar. Those people didn't deserve to die, but I had to hurt them. Not all of them died, and that's good. But blood needed to be spilled. I was whirling around like a mad red bone saw when the authorities (ACAB) shot me full of tranquilizer darts and took me to a Kentucky Fried Chicken and told the manager that "this is your last chance." Apparently the man I killed was not responsible for Charlotte's disappearance and death, nor were any of the people in 20 aware of my pain. But that was their fault, not mine. I cannot change the way I am. People need to realize that.

I was asked if I wanted to talk to the "widow" of the "man" I killed. I declined. Charlotte stilled haunted me and from that day on, until drugs entered my life in the 1960s, I remained as always: a stone, unturned, unwanted, and unused.

•••

This is the first in a continuing series.

—Follow Bennington Quibbits on Twitter: @BenningtonQuibb