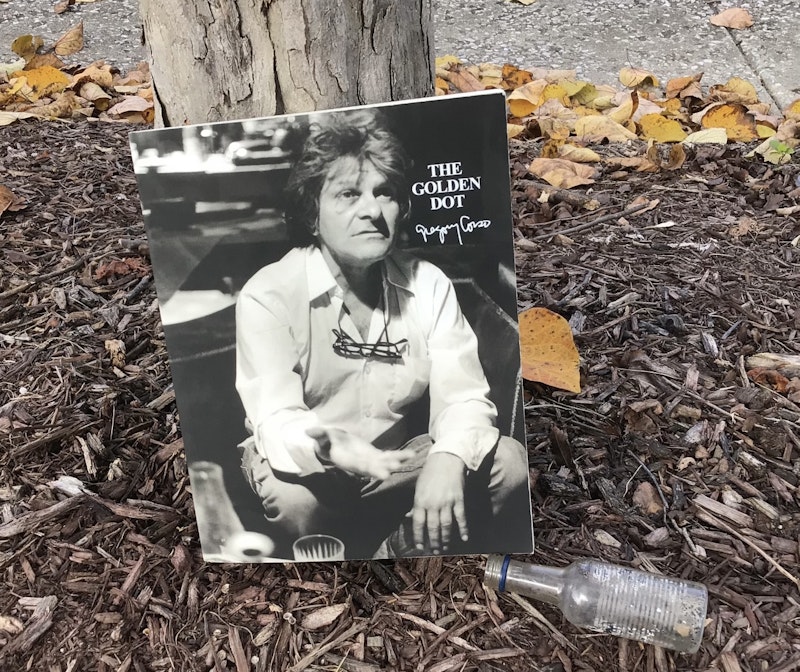

Golden Dot: The Last Poems, 1997-2000, a posthumous collection of Gregory Corso poems was edited by Raymond Foye and George Scrivani for Lithic Press over a period of years, a harrowing course of juggling mismatched manuscript pages. There’s Corso, shuffling poems like a three-card Monte hustler, or a Vegas dealer with a fresh deck of cards. The opening poem “Elegium Catullus/Corso”is a homage farewell to Allen Ginsberg, his close lifelong friend, mentor, rival, and confidante. It was written after returning from Ginsberg’s funeral. The poem ends with the line, “Toodle-loo.” Ginsberg always proclaimed Corso was the better poet to anyone who’d listen. Stark praise for the modern hoodlum Rimbaud, Nunzio, as he was known by friends and family in Little Italy. Gregorio was his confirmation name. He was born and bred in Greenwich Village on Bleecker Street. A native New Yorker, traveling the world but always returning to NYC. The intro page informs readers the poems have no order. “Thus the poem is beginning middle and endless.” Like a straight line turned on end, viewed simply as a mere dot.

This is how it happened:

“At the end

everything that was

dwindled into a dot;

the dot exploded into the void

and the beginning began again”

Here is a cosmic Corso, who viewed time as a linear map stretching across the universe of words on the highway to poetry. Yet point A doesn’t lead in a straight line to point B. Standing it on end and looking from above, you see the golden dot of eternity. The cosmological exit ramp to past, present, and future as one. A pinhead pointy poke in the bard’s poetic eyes. Corso was a word-slinger outlaw. A wise-guy trickster who communed with crows and talked to spirits both friendly and strange. Winding his way through roundabout trails, hiking alone, along uncharted territory and avenues of uncertainty in smoky dark bars or behind rusty steel bars. Listening keenly for a sound or some signs of affirmation. He could never be boxed in, caged or pigeonholed into conformity.

Patti Smith’s back cover blurb: “Place this book in your survival kit. Let Gregory Corso, the youngest, most high-spirited of the beat poets, guide you through the hallowed days, as he did for my generation. He will steer you through the minefields of existence, poem by poem, drawn from his irreverent, benevolent revolutionary heart.”

Corso did hard time as a youth of 13. He was locked up in The Tombs, NYC's infamous prison of untold terrors. On more than one occasion, he was sent off to Bellevue’s psych ward. A few years later, he was sentenced to Clinton Correctional State Prison in Dannemora, New York for his masterminding of a walkie-talkie burglary gang. Historically considered one of the state's toughest prisons, Corso credited his stay there for the process that formed him as anatural poet. Not only was Corso the youngest poet of the Beats, but also the youngest inmate in stir, protected by old-school gangsters who were amused by his antics, and protected the teenage Corso. They saved him from being raped in the communal showers. He became an entertaining personal cook and court jester to the old Capos and high-ranking mob bosses there. There, the old school mafioso’s took care of the upstart poet, encouraging him to read all he could. He survived by his quick wit, dumb luck and clever ripostes to get by. He occupied the former cell of Lucky Luciano which was furnished, among other prison luxuries, with an extensive library of classical poetry and literature. Corso began writing poetry while serving his stint, and it was his saving grace.

I didn’t know Corso, though the few times I met him, he was gregarious, funny, and friendly. I must’ve met him on good nights, hanging out drinking and carousing. He could be difficult and brutal, especially at poetry readings. He’d heckle poets and scream at audiences. There was no separation in his mind between the poet and the audience. Corso ripped down the curtains that divided the performer from the performance. He saw no difference from us and them. In a letter to his publisher at City Lights, Lawrence Ferlinghetti from 1957, Corso lamented: “I hate poetry and all its fucking ambitious son of a bitches who call me a showman because I act myself.”

Acting up and out is what he did best, rallyingagainst the staid, old-fashioned proper academe ivory tower poets.

One might say Corso, for all his bluster and bravado, was full of shit too, as you may round up the whole caboodle of those disaffected beatnik rabble rousers. One truth is certain, they’ve withstood the ultimate test of time and stand out as some of the greatest poets of the 20th century. Poetry is nothing without the poet behind the words. Corso told people that when he passes on he wants his gravestone to read, “Oops, I died,” ever the stand-up poet andcomedian.

A stanza of verse from his poem “Spirit” was chosen, defining his life and poetic soul:

Spirit is Life

It flows thru the death of me

endlessly like a river

Unafraid of becoming the sea