Now once upon a time, not too long ago, one of the most powerful men in the world was paying millions of dollars in hush money to the victims he had sexually assaulted.

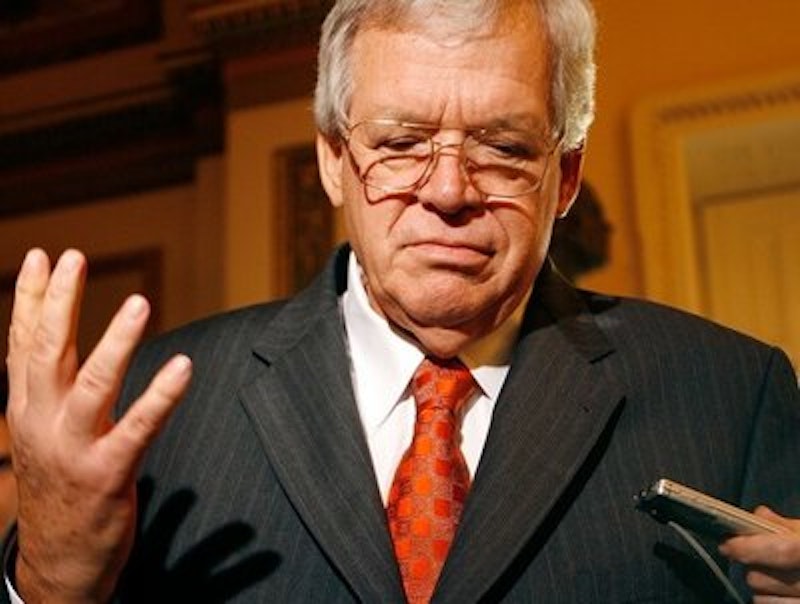

Yet Dennis Hastert, the longest-serving Republican Speaker of the House in history, has somehow already vanished from our collective memory banks. He lingered for a few postmortems in the prestige papers, and then that was that. A colorless, shambling man again faded into the scenery, his departure every bit as unremarkable as his arrival.

Hastert had seized control of Congress in 1999 to bring order to a rowdy Republican Party that had collapsed under the weight of Monica Lewinsky-mania and its consequences. Newt Gingrich, an entertaining but gaffe-prone blowhard who’d failed to deliver on his Contract with America, resigned the speakership after the GOP performed poorly during 1998’s “Lewinsky midterms.” Then Gingrich’s designated successor, Bob Livingston of Louisiana, chose to retire from public life after Hustler publisher Larry Flynt told the media that Livingston had engaged in extramarital relations.

This was the beginning of a real golden age for sex scandals and the subsequent resignations, pleas for forgiveness, and falls from grace. Gary Hart had opened the floodgates in the 1980s, taunting National Enquirer photographers to catch him if they could, but it was only after the Lewinsky liaison leaked that sex between consenting adults became sufficient to torpedo careers. In short order, cads on both sides of the aisle, from cherub-cheeked John Edwards on the left to suntanned Mark Sanford on the right, would bite the dust. As was the case with Sanford and the even randier Anthony Weiner, they sometimes came back—every political hack could come back, it seemed, given enough time, a makeover, and a sufficient number of mea culpas.

Then you had Hastert, the sort of no-nonsense Midwesterner who only cheated on his spouse with the power tools in his work shed. “He’s like an old shoe,” former House GOP Leader Robert Michel told The Washington Post in 1999. Mark Foley, a Florida congressman who would himself become embroiled in a bizarre sexting scandal with his pages, remarked that Hastert was the ultimate insider, a pro’s pro (one of Hastert’s accusers would attempt to raise alarms about him during Foley’s 2006 fall from grace, to no avail). Numerous profiles of Hastert highlighted his stolid demeanor and past amateur wrestling stardom (which, as far as I’ve been able to determine, didn’t extend past high school, due to the same sports injury that kept him out of the Vietnam War). He was the Man Who Got Things Done. He was the Dependable Guy.

And perhaps most importantly, he was the Dude Who Had Been Paying Off His Victims for Decades. Hastert’s entire rise to the pinnacle of power had vanishingly little to do with public service and everything to do with securing the millions of dollars in hush money needed to buy the silence of four students on the Yorkville High School wrestling team he’d coached and molested. Only after the IRS bothered to check his books, trying to make sense of the Congressman’s frequent cash withdrawals, was Hastert exposed. He wasn’t Speaker then, merely a private citizen who, according to an effusive 2008 newspaper profile, had been trying to “return to his humble beginnings.” “My number one concern was taking care of the people of the 14th Congressional District, to make sure you build mundane things like bridges so you can get back and forth across the Fox River,” he told that reporter.

Maybe his misdeeds would’ve mattered more if he were still in office. That might have bought him a few more headlines, a few minutes under the harsh glare of the media’s klieg lights and along the news crawl at the bottom of our HD screens, a chance to stand for something more than honorable mention on MSNBC’s list of the “top political sex scandals of 2015” (how, exactly, is molesting a bunch of unwilling participants a “sex scandal?”). But this kind of predatory behavior is repugnant, and our tolerance for it, tolerance for what it really and truly means, is limited, and so it came and went in near-record time. Penn State assistant coach Jerry Sandusky, famous for “polish bowling” with his youthful victims, raised eyebrows and questions because of his long association with a holier-than-thou college football program; Hastert’s less glamorous story offered plenty of disturbing answers, but few had the intestinal fortitude to spend an entire 24/7 news cycle hearing them discussed.

“I felt a special bond with our wrestlers, and I think they felt one with me,” Hastert wrote in his 2004 memoir Speaker: Lessons from Forty Years in Coaching and Politics. The title is bland, as befits a bland man, and the content contained therein offers little besides the public record of Hastert’s life leavened with plenty of banal insights (“Every now and then, I’d sense the light bulbs were starting to flick on in their minds and that made all that time together worthwhile,” he remarked of his time as a teacher). The book exists for the same reason most of these self-important celebrity documents do: look upon my works, ye mighty, and despair!

Yet Hastert’s most important work, his predation and the resulting lifetime cover-up, will remain forever unaddressed. “I could never get away with [lying],” he wrote of a failed attempt at deceiving his family about a sports injury, “So I made up my mind as a kid to tell the truth and pay the consequences.” He paid the consequences for this, too: 15 months in prison and a quarter-million dollar fine for unlawfully structuring the withdrawal of $950,000 in cash to avoid IRS reporting requirements, but he wasn’t prosecuted for the sexual abuse because the statute of limitations on those crimes had passed.

Speaking to the court, Hastert apologized for “mistreat[ing] athletes,” adding that what he did “was wrong and I regret it... I took advantage of them.” This means nothing, of course; he could have added some cheesy filler along the lines of “my thoughts and prayers are with the victims” without the slightest alteration to the insubstantial character of his remarks. Old Hastert was great for a long time, a great and powerful Oz hidden behind an ill-fitting business suit, but in the end he revealed himself as a pitiful old man, confined by disability to a wheelchair, mumbling apologetic bromides to a judge who likely hated his guts.

I don’t care about that. Hastert isn’t a modern-day Coriolanus or Titus Andronicus, a towering titan undone by overweening pride, but rather a piece of garbage who led a garbage life designed to conceal from view the disgusting misdeeds we viewers at home would instinctively consign to the garbage heap. Yet he was sold to us in those late-1990s newspaper profiles as a solid leader, a dependable hand who could steer the ship of state back on course after the crises of conscience and confidence caused by Bill Clinton and Newt Gingrich. He was, in other words, Someone We Could Trust.

Big Denny Hastert, that lumbering oaf, violated the trust placed in him. He transgressed in ways that make the Mark Sanford and John Edwards contretemps seem like small potatoes; he used a position of minor yet supreme power, that of the whistle-wielding, sweatpants-wearing Coach, to ruin the lives of a few high school boys, then gathered more power, actual political power, to keep paying them off. One of his victims died in the mid-1990s of complications related to HIV; it will never be known if Hastert was the direct or proximate cause of that, but he surely didn’t help this unfortunate person along life’s way.

The violated remain violated: no amount of money or forgiveness-begging can make them whole again. Hastert, who is elderly and ill and was already in the process of being forgotten while serving as Speaker, will elude infamy. His name will come up from time to time on those clickbait lists of DC “sex scandals” and, at least in the minds of the “beltway insiders” who thrive on this gossipy bullshit, will serve as a cautionary tale. Power corrupts, they might say, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. That doesn’t apply here: Hastert was corrupt long before he was truly powerful, and his grim story is perhaps more characteristic of the people vying to rule us than we would care to imagine. The bleeding-heart street activist and the doctrinaire libertarian may rise on the strength of their sweet words and strong handshakes, but the motivation for their megalomania may have much more to do with mankind’s basest interests than our best.