Whenever paganism enters a conversation about music the default talking point becomes heavy metal. The works of Black Sabbath, Slayer, and other raucous head-bangers are synonymous with deviant values and behaviors commonly thought of as anti-Christian. Pagan religion first gained a major association with irreverence during the Victorian era when ceremonial magician Aleister Crowley wrote The Book Of The Law and began practicing sex positive rituals. Crowley’s activity was part of a broader movement that sprung from the concept of free thinking, something vehemently opposed by the Church Of England; the Church’s repressive political influence made any deviation from Christian norms heretical. Belief in pagan spirituality then became an anti-authoritarian protest action connected to divergent political groups and cultural movements, from hippie Earth mothers to leftist intellectuals to goth nerds to new age eco-warriors.

By the late-20th century paganism had become something akin to the elemental/Earth worship that flourished throughout indigenous cultures prior to The Crusades. Just like their ancient forebears, modern pagans treat spirituality as an intimate way to connect Earth with the organic forces that once shaped the planet into a place defined by Arcadian beauty. Way before Crowley and the hard rockers of the post-WW2 era, musical references to pagan themes belonged to the vast archaic canon of British folk song, a body of music which few listeners would ever describe as rebellious.

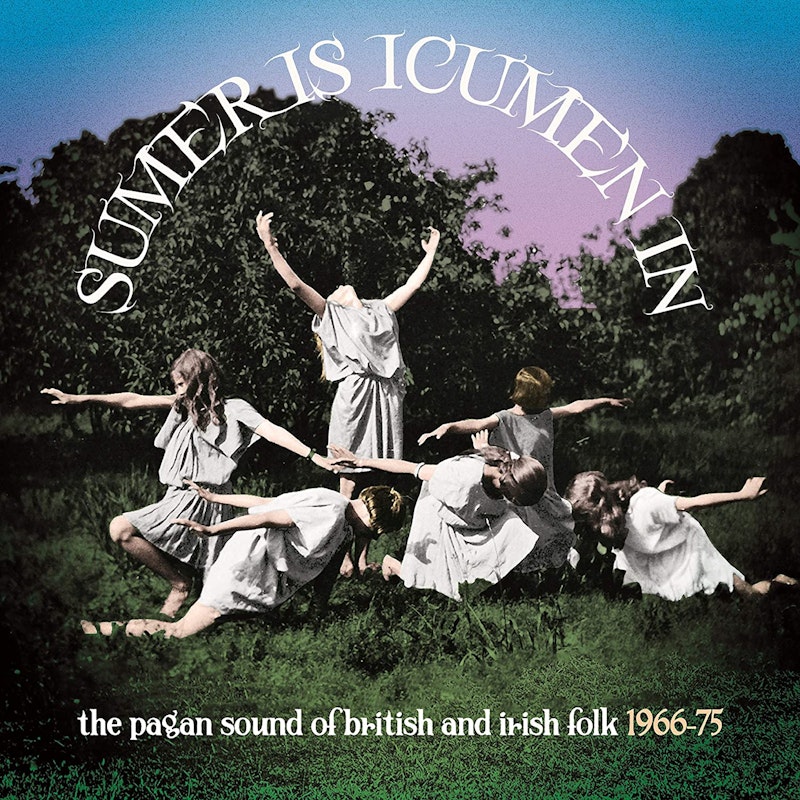

The Grapefruit label’s sonic omnibus Sumer Is Icumen In examines the arcane folk inspirations that made a permanent mark on some of 20th-century music’s most influential works. This strange chapter comes to life via three hours of music and the 40-page booklet of track notes that comprise the multi-media trip, a format that’s been a hallmark for Grapefruit (i.e., the label’s studious and essential triple c.d. retrospectives of library music giant Electric Banana and “exploito psych” hub Alshire Records).

The UK pop rock scene is well-represented here by Fairport Convention (with their proto-math rock take on Scottish epic “Tam Lin”), Traffic (whose cover of “John Barleycorn Must Die” remains the ultimate stoner version of this harvest time standard), The Strawbs, The Pentangle, The Incredible String Band, Marc Bolan, and the early projects of Sally & Mike “Tubular Bells” Oldfield. These stars’ rootsy spiritual works are placed in a fascinating context among those of other more offbeat and obscure artists.

Some of the least folkie groups turn in artifacts from the days when Carnaby Street was among the world’s great psychedelic capitals. Tracks by Anne Briggs, J.P. Sunshine, and Pink Floyd acolytes Chimera sound more like the background music for a dosed yoga session at the UFO Club than any Bronze Age revival. More brash music unfurls via the lumbering occult grunge-folk of Mr. Fox, acoustic prog-psych ensemble Amber, and singer-songwriter Archie Fisher; his loose/sitar-drenched rendition of quasi-pagan hymn “Reynardine” is anything but traditional.

The first major work of the “folk horror” film genre was 1973’s The Wicker Man. Its murder mystery plot deals with pagan concepts like the Maypole dance, sacrificial rites, and the subversion of puritanical morality. The film’s original soundtrack mixed gorgeous vocal-driven folk and moody ambient music, all tied together by the unique vision of NYC composer Paul Giovanni and his UK-based group Magnet; their musical adaptation of Robert Burns’ poem “Corn Rigs” is a high point of disc one. The contemplative chamber drone created by soundtrack artists Third Ear Band (their 1969 instrumental “Lark’s Rise“) also shows how early music could be a strong component of multi-media work.

A trip through pop culture history is far from the most complex ambition of Sumer Is Icumen In. The set works best as a paraphrasing of Earth worship’s central creation stories. Here and there lurid paeans to mischievous spirits, weird sex, and black magic are included and those will shock the average conservative Christian. Regardless, the bulk of this music comes from a place where the cycles of life and death are the world’s only omnipotent “super powers.”

The record’s most traditional artists treat us to rousing anthems of farming and harvest (the a cappella track “Green Grass“ by Wiccan duo Dave & Toni Arthur; Lal & Mike Waterson’s “The Scarecrow,” perhaps the most hallucinogenic non-drug inspired song ever recorded), love and lust (Staverton Bridge’s take on airy ancient sex ode “Captian Wedderburn’s Courtship”), and the rush of a good hunt (a pounding version of the “The White Hare” by pioneering folk revivalist Shirley Collins and her super group The Albion Band). Themes focused on mortality and vulnerability possess Parke’s ominous “Three Ravens,” yet another dusty English ballad. Its lyrics describe death as a catalyst for new life. A Scottish variation of this song—“Twa Corbies”—is also included in an organ-driven psych-folk update by Steeleye Span.

Finality’s reproductive power emanates from the definitive version of Scottish traditional tune "The Parting Glass,” originally the climax of a rare 1972 Midas label LP cut by Warrington, Cheshire quintet The Minor Birds. At the time of the song’s (likely) conception date in the early-1600s, a parting glass was also known as a stirrup cup. Its main purpose was to lend extra hospitality and courage to a guest preparing for a horseback ride off into the night presumably through some rough highlands. Teenage lead singer Sue Waywell imbues her delicate melodies with dramatic breadth conjuring up the mystic reverence of the winter solstice and its heavy influence on the lives of the farmers and druids of the pre-Christian world whose entire existence revolved around seasons. The song’s intensity reminds us that changes and endings are unstoppable forces: