I've always felt a little dumb for not liking classical music more. I'm not entirely oblivious to the appeal of Mozart or Beethoven or Liszt, but generally if I have a choice between listening to classical music and something else, the latter’s very likely to win. I never learned how to read music, and my knowledge of theory is non-existent—though other people manage to love the classics without that background. In one of those Hollywood movies where responsiveness to classical music demonstrates soul, intelligence and taste, I’d be the dull lump who loses the girl or is executed by the villain while one of the great masters plays.

There’s one odd exception to my general classical music philistinism, though. I often like contemporary classical compositions—or new music, as the cognoscenti call it. I'm largely oblivious to sonata form, but dissonance, weird squeaks, or ambient oddness are familiar to me from electronica, metal, and noise. Mozart can sound alien, but new music feels like a house I've been in before.

For example, I've been listening, with pleasure, to two recent contemporary classical albums; Canadian pianist Vicky Chow's performance of Michael Gordon's Sonatra (Cantaloupe Records) and the Swiss Kukuruz Quartet's disc Julius Eastman Piano Interpretations (Intakt Records).

Gordon is an American minimalist composer who didn't write much music for piano. In Sonatra, he jokingly said he was going to cover every note on the keyboard. The result is a piece that sounds as fiendishly difficult as it is; 15 minutes of manic tinkling designed to give your fingers blisters on their blisters. The music is percussive and repetitive, intricate patterns of notes played over and over before running down the keyboard to bash out another cluster, all the way from the delicate flutter of the high notes to rumbling bottom bashing. Chow, a member of the Bang on a Can ensemble, is a machine—both in the sense that her virtuosity seems inhuman, and because the music itself recalls aggressive electronic works like those of Aphex Twin (though even Richard D. James' laptop would probably overheat at the frantic pace set here.) And when Chow's finally finished, she runs through the piece again, with the piano in the unusual tuning of just intonation, producing an even more alien clatter.

It's ferocious and bizarre, while also managing to be a little corny and ridiculous—like listening to a player piano crank out thrash metal.

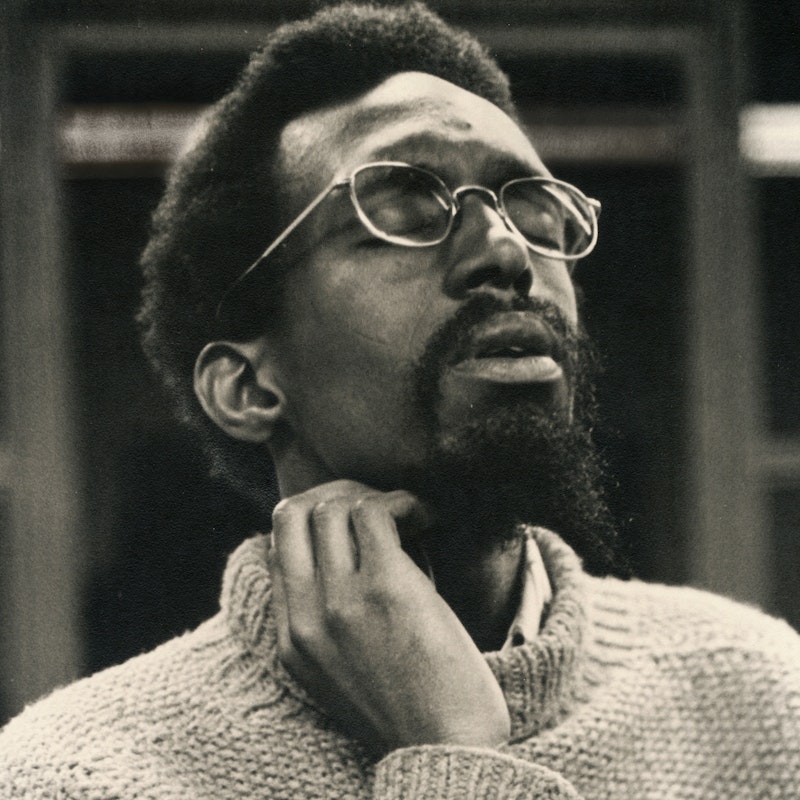

When you hear the name "Kukuruz Quartet" you probably think "string ensemble." It's not that, though; instead, Kukuruz consists of four pianos. The group's first disc is devoted to four compositions by gay African-American composer Julius Eastman, who died a virtual unknown in 1990. His work’s been revived from posthumous scores, though interpretations are still rare enough on the ground that this one feels like something of an event.

Eastman's music was influenced by minimalism too, but he's more meditative than Gordon. The interlocking patterns of the four keyboards echo and shimmer in layers atop each other, creating a throbbing ambience interrupted by occasional storm-like thundering crescendos on the eight and a half minute "Fugue No. 7." One of his most famous compositions, "Evil N****r," is built around an ominous melody that could serve as film suspense music, ringed around with rapid twittering. The track doesn't so much develop as breathe, with the same motifs drawing in and out over its 20-minute length. Much of "Buddha" sits on the edge of hearing; quiet shuffles and scratches on the keyboard that threaten to tip over into silence. It's not even clear how they got the noises from their instruments. It sounds like they've crawled into their pianos and are scrabbling with polite desperation to get out.

Often new music—or new art of any kind—is seen as difficult or challenging; traditional forms are supposed to be more accessible. And no doubt they are for some people. It's also true, though, that old art requires a different context and perspective, which can be difficult to wedge yourself into. The great old composers are for the ages, but at the same time, we're all stuck in the time we're in. Nothing against people speaking across the centuries, but sometimes it's easier to connect with someone talking to you now.