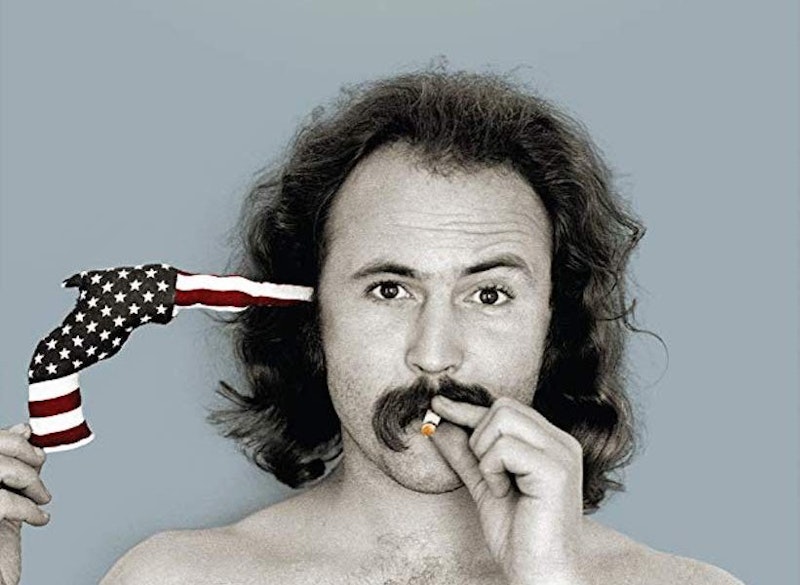

Few celebrities as famous as David Crosby speak with as much candor about their peers. Off the top of my head: Quincy Jones, Anjelica Huston, John Lennon… I’m drawing a blank. Who else is at once as openly egotistical and self-effacing as David Crosby? A new documentary directed by A.J. Eaton and produced by lifetime rockstar sycophant Cameron Crowe, David Crosby: Remember My Name, is a puff piece, but a fine one, starring one of rock music’s most entertaining Zeligs. The title is a play on Crosby’s hopelessly stoned 1971 solo album If I Could Only Remember My Name, but the movie isn’t nearly difficult or inscrutable enough to deserve that name. Recorded in the aftermath of his girlfriend Christine Hinton’s death in a car accident, If I Could Only Remember My Name is closer to Pink Floyd or Van Dyke Parks than anything he’s well known for (if anything these days, besides the persona).

Crosby has written some great songs ("What's Happening?!?!,” “Everybody’s Been Burned,” “I See You,” "Dolphin's Smile"), co-written some even greater songs (“Eight Miles High,” “So You Want to Be a Rock ’n’ Roll Star,” “Wooden Ships”), and covered some of the best songs ever written (“Mr. Tambourine Man,” “My Back Pages,” “Spanish Harlem Incident”). If I Could Only Remember My Name is a true pop curio, a record that has so much more to give than any Byrds record that isn’t Younger Than Yesterday. It’s the most pleasant grieving album I can think of. Some people will hear it.

But this music has largely left popular consciousness. Besides the Byrds’ Dylan covers, what are we hearing in movies, on TV, and commercials? Too much Hendrix and CCR. Crosby is scarcely found. And yet, at the brink of the 2020’s, Crosby is the most famous and respected member of The Byrds and CSN—only Neil Young eclipses him. He’s the greater artist, but Crosby is all personality. If he weren’t brash and eccentric, he’d be Chris Hillman. (Even happy and sober, Crosby still comes off sour. Reconciling his anger management issues with his beautiful, soaring voice over gentle music is the film’s inner question, never resolved.)

Crosby’s been most enjoyable as an observer, a gadfly with a big mouth and an extraordinary run of luck: discovering Joni Mitchell in a Florida coffeehouse and producing her first album (he says in the documentary that, “I didn’t do a great job, but I captured her essence”). He saw John Coltrane play in a tiny club on too much acid, went to the bathroom to calm down, only to have “Trane” kick open the stall while playing with the most passion and volume Crosby has ever seen in his life. He was in the studio with The Beatles, and he tagged along to their American press conferences, always observing, taking notes.

Early days, 1966, one of The Doors’ first shows at the Whiskey A-Go-Go. Crosby walked in wearing sunglasses, high on LSD, and Jim Morrison walked right up to him and took the shades off his face: “You can’t hide.” Crosby has hated Morrison and The Doors ever since, and he never lets an opportunity to shit on him or Ray Manzarek pass (his Twitter is, naturally, a blast—unlike most 77-year-old rockstars, he’ll probably reply to you). And of course there’s Woodstock, a brief dream on a loan never repaid. There’s some great footage from The Dick Cavett Show taped just hours after Crosby, Stills, and Nash got back to Manhattan from Woodstock (Stills shows off his muddy jeans). There are limp gestures toward the hope of the time, but most of that has evaporated—whether Crosby knows it or not, I’m not sure. I think it could go either way.

But this is a standard rock doc. Crosby’s drug addiction is covered, and with most other subjects, this would be a pat rise and fall story, predictable five steps away. But Crosby himself makes this movie what it is—interesting—because he’s at once so completely full of himself and equally self-aware and self-critical, eager to admit failure and regret over apologies never made. “Once the adrenaline gets going, I can’t stop. Getting mad is my worst problem.” After reconciling for a decade or so, Crosby is once again persona non grata with Graham Nash and Stephen Stills, a particularly remarkable feat for one of the most accomplished assholes of all time. In 2018, Nash said that he hadn’t spoken to Crosby “in over two years… this is after 45 years of constant, everyday contact.” Late in the documentary, we see the final CSN performance, an abysmal rendition of “Silent Night” at the White House in December 2015. The audience, including Barack and Michelle Obama, can barely hide their disdain. And what’s remarkable is that these guys can still sing: at one point, we see Crosby rehearsing before a solo show in a stairwell, no mics or in-ears or bed tracks to hide behind. He can still belt, and he sounds fantastic.

He points out that, “of all the Byrds, of CSN, I was the only one to never write a hit.” No matter—he’ll be remembered by more than Nash and Stills combined. Morbid as it is, that’s what this movie is: a legacy sweeping, a broad synopsis of the key moments and eras of an artist’s life. Remember My Name is only 95 minutes, and a subject as candid, passionate, and mildly hostile, whose lush, emotional music is at such odds with his caustic personality. This man deserved a three-hour documentary, whether it was on Netflix or in the 47 theaters it’s playing in right now. Remember My Name is another pamphlet documentary aimed at arthouse mollusks and maybe some people who know him from Twitter and saw it a trailer before Midsommar.

Eaton doesn’t deviate from the blueprint besides a semi-stoned looseness with chronology—Crosby’s talking head interviews anchor the film and justify its existence. Put David Crosby in front of a camera and let him talk for however long he’ll tolerate it. He’s a great storyteller, and he doesn’t appear enough. Tell us more about Jimi, Joni, Janis, John (Coltrane, Lennon). I find Frank Zappa much less interesting than David Crosby, but his 2016 documentary Eat That Question—comprised entirely of interviews with Zappa and no additional footage, voiceover, or title cards added—was a more compelling film. It took us through a man’s public life, as broadcast and recorded over five decades. That’s it. It was fantastic.

Crosby’s such a canny observer, willing to make a mess and worry about it later than his more guarded contemporaries (in Dylan’s case, his aloofness is aesthetic—in McCartney’s, selfish obfuscation). His contributions are welcome, and his passion for music is moving and infectious. Remember My Name is exactly that: a postcard, a photo to put in a frame on your desk. It isn’t the multi-volume memoir we know that’s in him, waiting to be dictated or told to a camera crew. I’ll be there, front row.

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @nickyotissmith