This is part of a series on 1980s comedies. The last entry, on American Werewolf in London, is here.

In earlier Monty Python films, jokes were often deflationary. Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975) famously didn't include horses for its Arthurian heroes; instead, the knights wandered around with servants who thumped coconuts together to sound like horse hooves while Arthur (Graham Chapman) mimed holding reins. Holy Grail ends in a giant anti-climax, as Arthur’s arrested by contemporary English policeman, and the narrative grinds to a halt. The grandeur of myth trips over banality. Low-budget make-dos create adventures that are smaller than life—or at least as small as a transparently fake killer bunny.

The Meaning of Life, from 1983, has a bigger budget and more grandiose ambitions. Rather than exposing the mechanism of filmmaking as a way to puncture pretension, it revels in the hyperbole of film fantasy. The movie opens with a bravura live-action short film by Python animator Terry Gilliam, in which throwback accountants of the Crimson Permanent Assurance turn their ramshackle offices into a pirate ship, stripping the assets of soulless corporate boardrooms with swords made of ceiling fans and filing cabinets turned into drawer-shooting canons. Other set pieces include a number of old-style Hollywood music numbers, and a trek across the universe with Eric Idle musing on the size of the galaxy as animation and effects spin him out across space-time. (Space-time looks surprisingly like a nude woman, as it turns out.)

Roger Ebert, who wasn’t thrilled with the film, looked at the bigness of The Meaning of Life and concluded it was an exercise in "One-Upmanship." The Meaning of Life, Ebert said, was a movie "consumed with a desire to push us too far." The Python crew is trying to blow up the bounds of good taste as a kind of boast. They’re preening themselves on their large-scale inappropriateness.

There's something to that—especially in the restaurant scene in which Terry Jones puts on a fat suit, spews streams of vomit, and then finally explodes in a nightmare cascade of bodily fluids after eating one thin wafer too many. It’s a skit that revels in its own flagrant, preposterous disgustingness. It demands you be repulsed—or dares you not to be.

But the very enormousness of the provocation is a kind of nudge. There isn't much effort to make Jones' predicament realistic; vomiting once would be gross, vomiting like the Exorcist on vomiting steroids looks silly. Similarly, the giant musical number in which Michael Palin plays a Catholic dad with scads of children while nuns kick their heels up in the background and cardinals dance and twirl is certainly mocking pro-life dogma. ("Every sperm is sacred/every sperm is great/If a sperm is wasted/God gets quite irate.")

But it's so excessive that it ends up mocking its own mockery. Satire is crushed beneath the tiny shoes of all those children, marching past the screen in an endless line, on their way to be sold for medical experimentation since daddy can't afford to keep them any more. The Pythons, in short, are not cosigning a sincere pro-choice message. Just in case anyone was confused about that.

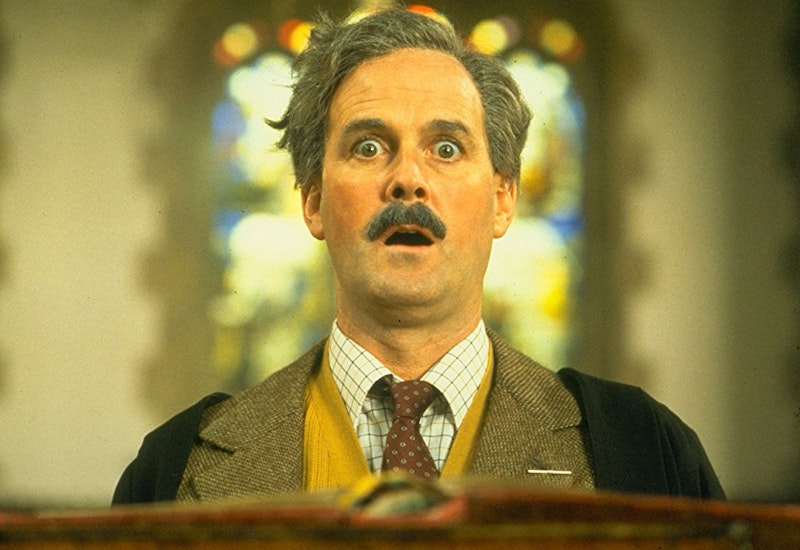

By veering into musical theater, the Pythons also veer into camp. To tackle the deep question of the meaning of life, they turn to shallow, flamboyant spectacle. One of the funniest skits involves a fusty don (John Cleese) who tries to keep his students attention for a sex ed. class. So he strips down and fucks his wife while talking sternly about vaginal juices and stiffening penises. His wife thrusts dutifully beneath him, but the kids just pass notes back and forth about unrelated matters or try to catch a glimpse of a soccer match through the window. You try to teach the young ones about the birds and the bees, and where does it get you? As the Pythons point out in another skit, even if you heard the true meaning of life, you'd be too distracted by hats or marauding accountants to pay attention.

Monty Python's humor has an edge of cruelty. That's not because it kicks people or groups as because it jumps up and down on sense itself. The Meaning of Life, the group's final film, is also their most explicit embrace of absurdity not just as tactic, but as a philosophy. They’re making a big statement, complete with bells and whistles, zithers and dancing angels. And big statements, Python says, like the meaning of life, add up to nothing.